User:Psantos0925/sandbox

Psantos0925 (talk) 02:21, 24 October 2015 (UTC)

| This is a user sandbox of Psantos0925. A user sandbox is a subpage of the user's user page. It serves as a testing spot and page development space for the user and is not an encyclopedia article. |

History[edit]

Feminist science fiction (SF) distinguishes between female SF authors and feminist SF authors.[1] Both female and feminist SF authors are historically significant to the feminist SF subgenre as female writers have increased women's visibility and perspectives in SF literary traditions, while the feminist writers have foregrounded political themes and tropes in their works.[1] Because distinctions between female and feminist can be blurry, whether a work is considered feminist can be debatable, but there are generally agreed-upon canonical texts, which help define the subgenre.

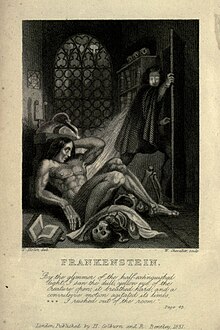

As early as the English Restoration, female authors were using themes of SF and imagined futures to explore women's issues, roles, and place in society. This can be seen as early as 1666 in Margaret Cavendish's The Blazing World, in which she describes a utopian kingdom ruled by an empress. This foundational work has garnered attention from some feminist critics, such as Dale Spender, who considered this a forerunner of the science fiction genre, more generally.[2] Another early female writer of science fiction was Mary Shelley. Her novel Frankenstein (1818) dealt with the asexual creation of new life, and has been considered by some a reimagining of the Adam and Eve story.[3] In the same year, Mary E. Bradley Lane authored Mizora: A Prophecy where women chemically synthesize food.[1]

Women writers, who could be considered the first feminist SF authors, were those involved in the utopian literature movement of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These texts, emerging during the first wave feminist movement, often addressed issues of sexism through imagining different worlds that challenged gender expectations. In 1892, poet and abolitionist Frances Harper published her novel Iola Leroy at the age of 67 that is also known as one of the first novels published by an African American woman. Set during the antebellum South, the utopian fiction follows the life of a mixed race woman with mostly white ancestry and records the hopes of many African Americans for social equality during Reconstruction.[4] The novel addresses not only issues of gender, but of race as well. Two American Populist publishers, A.O. Grigsby and Mary P. Lowe, published a book, which explores issues of gender norms and structural inequality titled NEQUA or The Problem of the Ages (1900). This recently rediscovered novel displays familiar feminist SF conventions, which include a heroine narrator who masquerades as a man, the exploration of sexist mores, and the description of a future hollow earth society where women are equal.

In addition to NEQUA and other early feminist works, The Sultana's Dream (1905), by Bengali Muslim feminist Roquia Sakhawat Hussain, engages with the limited role of women in colonial Bangladesh. Through depicting a gender-reversed purdah in an alternate technologically futuristic world, Hussain illustrates the potential for cultural insights through role reversals early on in the subgenre's formation. Along these same lines, Charlotte Perkins Gilman explores and critiques the expectations of women and men by creating a single-sex world in Herland (1915).

During the 1920s and 1930s, much of the popular pulp science fiction magazines exaggerated views of masculinity and featured sexist portrayals of women.[5] These views would be subtly satirized by Stella Gibbons in Cold Comfort Farm (1932)[6] and much later by Margaret Atwood in The Blind Assassin (2000). As early as 1920, however, women writers of this time, such as Clare Winger Harris (The Runaway World, 1926) and Gertrude Barrows Bennett (Claimed, 1920), published science fiction stories written from female perspectives and occasionally dealt with gender and sexuality based topics.

The Post-WWII and Cold War eras were a pivotal and often overlooked period in feminist SF history.[1] During this time, female authors utilized the SF genre to assess critically the rapidly changing social, cultural, and technological landscape.[1] Women SF authors during the post-WWII and Cold War time periods directly engage in the exploration of the impacts of science and technology on women and their families, which was a focal point in the public consciousness during the 1950s and 1960s. These female SF authors, often published in SF magazines such as The Avalonian, Astounding, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and Galaxy, which were open to new stories and authors that pushed the boundaries of form and content.[1]

At the beginning of the Cold War, economic restructuring, technological advancements, new domestic technologies (washing machines, electric appliances),[7] increased economic mobility of an emerging middle class,[8] and an emphasis on consumptive practices,[9] carved out a new technological domestic sphere where women were circumscribed to a new job description - the professional housewife.[10][11] Published feminist SF stories were told from the perspectives of women (characters and authors) who often identified within traditional roles of housewives or homemakers, a subversive act in many ways given the traditionally male-centered nature of the SF genre and society during that time.[1]

In Galactic Suburbia, author Lisa Yaszek recovers many women SF authors of the post-WWII era such as Judith Merril, author of “That Only a Mother” (1948), “Daughters of Earth” (1952), “Project Nursemaid” (1955), “The Lady Was a Tramp” (1957); Alice Eleanor Jones “Life, Incorporated” (1955), “The Happy Clown” (1955), “Recruiting Officer” (1955); and Shirley Jackson “One Ordinary Day, with Peanuts” (1955) and “The Omen" (1958).[1] These authors often blurred the boundaries of feminist SF fiction and feminist speculative fiction, but their work laid substantive foundations for Second Wave Feminist SF authors to directly engage with the feminist project. “Simply put, women turned to SF in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s because it provided them with growing audiences for fiction that was both socially engaged and aesthetically innovative.” [12]

By the 1960s science fiction was combining sensationalism with political and technological critiques of society. With the advent of second wave feminism, women’s roles were questioned in this "subversive, mind expanding genre."[13] Three notable texts of this period are Ursula K. Le Guin's The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), Marge Piercy's Woman on the Edge of Time (1976) and Joanna Russ' The Female Man (1970). Each highlights the socially constructed aspects of gender roles by creating worlds with genderless societies.[14] Two of these authors were pioneers in feminist criticism of science fiction during the 1960s and 70s through essays collected in The Language of the Night (Le Guin, 1979) and How To Suppress Women's Writing (Russ, 1983). Men also contributed literature to feminist science fiction. Samuel R. Delaney's short story, "Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones" (1968), which won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story in 1970, follows the life of a gay man that includes themes involving sadomasochism, gender, significance of language, and when high and low society encounter one another .[15] Octavia Butler's Kindred (1979) tells the story of an African American woman living in the United States in 1979 who uncontrollably time travels to the antebellum South. The novel poses complicated questions about the nature of sexuality, gender, and race when the present faces the past.[16]

Feminist science fiction continues on into the 1980's with Margaret Atwood's novel The Handmaid's Tale (1985), a dystopic tale of a theocratic society in which women have been systematically stripped of all liberty. The book was motivated by fear of potential retrogressive effects on women's rights. Sheri S. Tepper is most known for her series The True Game, which explore the Lands of the True Game, a portion of a planet explored by humanity somewhere in the future. In November 2015, she received the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement for this series.[17][18] Tepper has written under several pseudonyms, including A. J. Orde, E. E. Horlak, and B. J. Oliphant.[19] Carol Emshwiller is another feminist SF author who's best known works are Carmen Dog (1988), The Mount (2002), and Mister Boots (2005). Emshwiller had also been writing SF for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction since 1974.[20] She won the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement in 2005 for her novel The Mount (2002).[21] This novel explores the prey/predator mentality through an alien race.[22] Another author of the 1980's, Pamela Sargent has written the "Seed Series", which included Earthseed, Farseed, and Seed Seeker (1983-2010), the "Venus Series" about the terraforming of Venus, which includes Venus of Dreams, Venus of Shadows, and Child of Venus (1986-2001), and The Shore of Women (1986). Sargent is also the 2012 winner of the Pilgrim Award for lifetime contributions to SF/F studies. Lois McMaster Bujold has won both the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award for her novella The Mountains of Mourning, which is part of her series the "Vorkosigan Saga" (1986-2012). This saga includes points of view from a number of minority characters, and is also highly concerned with medical ethics, identity, and and sexual reproduction.

More recent science fiction authors illuminate injustices that are still prevalent. At a time of LA Riots, Japanese- American writer Cynthia Kadohata's work In the Heart of the Valley of Love (1992) was published. Her story, set in the year 2052, examines tensions between two groups as defined as those who "have" and the "have-nots" through the eyes of a nineteen year old girl who is of Asian and African decent. [23] Nalo Hopkinson's Falling in Love with Hominids (2015) is a collection of her short stories that range from historical fantasies involving colonialism in the Caribbean, ethnic diversity in the land of Faerie, age manipulation, among others.[24]

In the early 1990's, a new award opportunity for feminist SF authors was created. The James Tiptree, Jr. Award is an annual literary prize for works of science fiction or fantasy that expand or explore one's understanding of gender. Science fiction authors Pat Murphy and Karen Joy Fowler initiated this subsequent discussion at WisCon in February 1991. The authors publishing in feminist SF after 1991 were now eligible for an award named after one of the genre's beloved authors. Karen Joy Fowler herself is considered a feminist SF writer for her short stories, such as "What I Didn't See", for which she received the Nebula Award in 2004. This story is a homage Alice Sheldon, and describes an gorilla hunting expedition in Africa. Pat Murphy won a number of awards for her feminist SF novels as well. For her second novel The Falling Woman (1986), a tale of personal conflict and visionary experiences set during an archeological field study for which she won the Nebula Award in 1988. She won another Nebula Award in the same year for her novella, "Rachel in Love". Her short story collection, "Points of Departure" (1990) won the Philip K. Dick Award, and her 1990 novella "Bones" won the World Fantasy Award in 1991.[25]

Other winners of the James Tiptree, Jr. Award include "The Sparrow" by Mary Doria Russell (1996), "Black Wine" by Candas Jane Dorsey (1997), Redwood and Wildfire by Andrea Hairston (2011)[26], The Drowning Girl by Caitlin R. Kiernan (2012), "The Carhullan Army" by Sarah Hall (2007), Ammonite by Nicola Griffith (1993), and "The Conqueror's Child" by Suzy McKee Charnas (1999). All of these authors have had an important impact in the SF world by adding a feminist perspective to the traditionally male genre.

Eileen Gunn's science fiction short story "Coming to Terms" received the Nebula Award in the United States (2004) and the Sense of Gender Award in Japan (2007), and has twice been nominated for the Hugo Award, Philip K. Dick Award and World Fantasy Award, and short-listed for the James Tiptree, Jr. Award. Her most popular anthology of short stories is Questionable Practices, which includes stories "Up the Fire Road" and "Chop Wood, Carry Water". She also edited "The WisCon Chronicles 2: Provocative Essays on Feminism, Race, Revolution, and the Future" with L. Timmel Duchamp. [27] Duchamp has been known in the feminist SF community for her first novel Alanya to Alanya (2005), the first of a series of five titled "The Marq’ssan Cycle". Alanya to Alanya is set on a near-future earth controlled by a male-dominated ruling class patterned loosely after the corporate world of today. Duchamp has also published a number of short stories, and is an editor for Aqueduct Press. Lisa Goldstein's novel Dark Rooms (2007) is one of her better known works, and another of her novels The Uncertain Places won the Mythopoeic Award for Best Adult Novel in 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Yaszek, Lisa (2008). Galactic suburbia: Recovering women's science fiction. Ohio, US: The Ohio State University Press. pp. 1–65. ISBN 0814251641.

- ^ Spender, Dale (1986). Mothers of the Novel. London: Pandora Press. p. 43. ISBN 0863580815.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Brian Aldiss has argued that Frankenstein should be considered the first true science fiction story, because unlike in previous stories with fantastical elements resembling those of later science fiction, the central character "makes a deliberate decision" and "turns to modern experiments in the laboratory" to achieve fantastic results. See The Detached Retina: Aspects of SF and Fantasy by Brian Aldiss (1995), page 78.

- ^ Borgstrom, Michael (2006). "Face Value: Ambivalent Citizenship in "Iola Leroy"". African American Review.

- ^ Lisa Tuttle in Clute and Nicholls 1995, p. 1344.

- ^ Dryden, Caroline (2014-02-25). Being Married, Doing Gender: A Critical Analysis of Gender Relationships in Marriage. Routledge. ISBN 9781317725121.

- ^ "History of Household Technology-Science Tracer Bullet>". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ^ Suddath, Claire (2009-02-27). "The Middle Class". Time. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ^ Cohen, Lizabeth (June 2004). "A Consumers' Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America" (PDF). Journal of Consumer Research. doi:10.1086/383439.

- ^ "WGBH American Experience: Tupperware! PBS". American Experience. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ^ "Partners in Winning the War: American Women in World War II". www.nwhm.org. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ^ Yaszek, Lisa (2008). Galactic suburbia: Recovering women's science fiction. Ohio, US: The Ohio State University Press. p. 22. ISBN 0814251641.

- ^ Lisa Tuttle in Clute and Nicholls 1995, p. 424.

- ^ Helford, p.290.

- ^ Styrsky, Stefen (2005). "The desperate and the human". Lambda Book Report.

- ^ Spender, Dale (1986). Mothers of the Novel. London: Pandora Press. p. 43. ISBN 0863580815.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Locus Online News » World Fantasy Awards Winners 2015". www.locusmag.com. Retrieved 2015-11-14.

- ^ "World Fantasy Convention 2015 -- Life Achievement Awards". www.wfc2015.org. Retrieved 2015-11-14.

- ^ {{Cite web|title = isfdb science fiction » Sheri S. Tepper - Summary Bibliography|url = http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/ea.cgi?173

- ^ "Emshwiller, Carol". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ "Emshwiller, Carol". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Robert Freeman Wexler interviews Carol Emshwiller, "Emshwiller Interview" Laconic Writer, posted: Jan 19th 2010, accessed: Jun 6th, 2010

- ^ "Cynthia Kadohata Biography". Encyclopedia of World Biography.

- ^ Heller, Jason (August 11, 2015). "'Hominids' Is A Deeply Human Collection of Speculative Fiction". NPR Books. NPR.

- ^ World Fantasy Convention. "Award Winners and Nominees". Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "2011 Tiptree Award Winner announced". James Tiptree, Jr. Literary Award Council. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ Gunn, edited by L.Timmel Duchamp & Eileen (2007). The WisCon chronicles. provocative essays on feminism, race, revolution, and the future. Seattle, WA: Aqueduct Press. ISBN 1933500204.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|first1=has generic name (help)