Solar eclipse of June 19, 1936

| Solar eclipse of June 19, 1936 | |

|---|---|

| Type of eclipse | |

| Nature | Total |

| Gamma | 0.5389 |

| Magnitude | 1.0329 |

| Maximum eclipse | |

| Duration | 151 s (2 min 31 s) |

| Coordinates | 56°06′N 104°42′E / 56.1°N 104.7°E |

| Max. width of band | 132 km (82 mi) |

| Times (UTC) | |

| Greatest eclipse | 5:20:31 |

| References | |

| Saros | 126 (43 of 72) |

| Catalog # (SE5000) | 9367 |

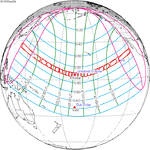

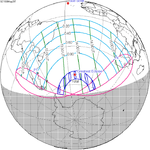

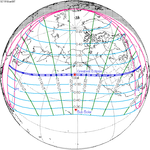

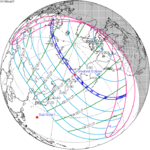

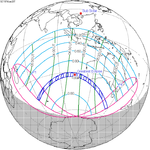

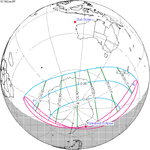

A total solar eclipse occurred at the Moon's descending node on Friday, June 19, 1936 (Thursday, June 18, 1936 east of the International Date Line). A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby totally or partly obscuring the image of the Sun for a viewer on Earth. A total solar eclipse occurs when the Moon's apparent diameter is larger than the Sun's, blocking all direct sunlight, turning day into darkness. Totality occurs in a narrow path across Earth's surface, with the partial solar eclipse visible over a surrounding region thousands of kilometres wide. The path of totality crossed Europe and Asia. The full phase could be seen in Greece, Turkey, USSR, China and the Japanese island of Hokkaido. The maximum eclipse was near Bratsk and lasted about 2.5 minutes. The Sun was 57 degrees above horizon, gamma had a value of 0.539, and the eclipse was part of Solar Saros 126.

The Evening Standard reported that the "preparations for to-day's eclipse have been going forward for the past two years", and that a British expedition led by amateur astronomer R. L. Waterfield saw "excellent atmospheric conditions" from its observation point on Cap Sunium.[1] Similar observations were made by teams in Hokkaido, some hours later, allowing their observations of the Sun's corona to be compared "to find out whether any changes in shape or in detail of the corona have taken place in this interval".[1] A Russian team in Krasnoyarsk reported successful observation from a high-altitude balloon, where scientists "hoped to make observations at a height of some 15 miles".[1] There were also observers in the south of Greece, from Greece, Italy and Poland, the latter of which were "successful in obtaining cinematograph pictures of the eclipse".[1] Several long prominences (more than a million miles long) were observed, as well as the planet Venus.[1]

A United States expedition in Siberia conducted experiments on the ionosphere, with the Associated Press reporting that "indications that the earth's electrified roof, which, many miles above the surface of the globe, reflects back radio impulses, is formed mostly as a result of ultra-violet sun radiations appeared in preliminary results of the solar eclipse observations".[2]

Observations[edit]

Soviet Union[edit]

Except for the total solar eclipse of June 29, 1927, which was only visible from the sparsely populated Arctic Ocean coast, this was the first total solar eclipse visible within the Soviet Union since its founding (the previous one was in 1914 when it was still ruled by Russian Empire). 28 Soviet teams (including 17 astronomical observation teams and 11 geophysical observation teams)[3] and 12 international teams from France, the United Kingdom, the United States, Italy, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, the Netherlands, China, Japan and Poland made observations in the Soviet Union[4]. There were 370 astronomers in the teams. To offer better conditions for the 70 foreigners among them, the Central Committee of All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) promoted a policy to reduce railway and water transportation fair by 50%[5]. The Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union established a special committee and made preparations for 2 years. The government raised 60,000, 365,000 and 400,000 rubles respectively in 1934, 1935 and 1936. Experts from the Leningrad Astronomical Institute manufactured 6 coronagraphs with a diameter of 100 mm and a focal length of 5 metres, distributed to Pulkovo Observatory, Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Moscow branch of the All-Union Astronomical and Geodetic Society, Institute of Astronomy of Kharkiv National University, V. P. Engel'gardt Astronomical Observatory and Ulugh Beg Astronomical Institute. Besides observations on the ground, balloons[6] and aircrafts[7] were also used.

Among them, Pulkovo Observatory and its Simeiz branch (now Crimean Astrophysical Observatory) sent 3 teams. The first studied the chromosphere and solar prominences in Akbulak, Orenburg Oblast, led by Boris Gerasimovich, chairman of the Special Committee for Solar Eclipse Observation of the Academy of Sciences. The second went to Sara, Orenburg Oblast, led by Gavriil Adrianovich Tikhov. The third studied the corona in Omsk, led by Innokenty Andreevich Balanovsky. The team of the Sternberg Astronomical Institute went to the village of Bochkarev (Бочкарёв) in the suburbs of Kuybyshevka (now Belogorsk, Amur Oblast) to study the spectrum of the chromosphere and corona, the polarization of the corona and the light bending in gravitational fields proposed by the theory of relativity. The team of Kharkiv Observatory studied the luminosity, polarization and chromospheric spectrum of the corona in Belorechensk, Krasnodar Krai, led by Nikolai Barabashov. The team of the Georgian National Astrophysical Observatory studied coronal radiation. The team of the Moscow branch of the All-Union Astronomical and Geodetic Society made standard coronagraph observations and led amateur observations nationwide. The team of V. P. Engel'gardt Astronomical Observatory studied the visible spectrum of the corona with diffraction gratings and took images of the corona with standard coronagraphs in Kostanay Region in today's Kazakhstan.[8][9].

An American team of 24 people led by Donald Howard Menzel went to Akbulak together with the Pulkovo Observatory team. A team of 4 astronomers of Arcetri Observatory, Italy led by Giorgio Abetti went to Sara together with another team of the Pulkovo Observatory[3].

Japan[edit]

Japan sent 20 astronomy observation teams and 18 geophysics observation teams to Hokkaido. In addition, teams from the United Kingdom, the United States, India, China, Czechoslovakia and Poland also went to Hokkaido. Some were successful and some were not. Interestingly, another total solar eclipse of August 9, 1896 was also visible in the coastal town Eshashi of Esashi District, which received many foreign scientists at that time. Therefore, despite the inconvenient transportation, Kwasan Observatory of Kyoto University and a Chinese team still selected it as the observation site[10].

China[edit]

In November 1934, astronomer Gao Lu organized the Chinese Solar Eclipse Observation Committee shortly after the establishment of the Purple Mountain Observatory, to prepare for observations of this eclipse in 1936, and the solar eclipse of September 21, 1941 (another total solar eclipse in 1943 was also visible in Northeast China, the Soviet Union and Japan, but there was no plans or actual activities of any kind of observations in China). The committee was inside the Institute of Astronomy, with Cai Yuanpei being the chairman, and Gao Lu the secretary-general. It asked for a fund of 30,000 from the government during the preparation, and received another 120,000 from the British, French and American portions of the Boxer Indemnities Comittee. Although the path of totality of this eclipse passed through northeast China, it was relatively remote located on the Sino-Soviet border, and was already under control of Manchukuo, a Japanese puppet state. In the end, 2 teams were sent abroad. This was the first time that Chinese scientific observation teams made observations abroad.

One team consisted of only Zhang Yuzhe and Li Heng, going to Siberia, the Soviet Union. They initially planned to go to Orenburg Oblast with better weather conditions, but because the time was limited, they finally chose Khabarovsk. The two took a ship from Shanghai to Japan on May 31, then transferred to a train to Tsuruga and then transferred again a ship, arriving in Vladivostok on June 9. After staying there for 2 days, they took an international train and arrived in Khabarovsk on June 11. The goals include taking images of the corona, measuring the time of the eclipse, and comparing the darkness of the sky during totality with that of twilight. On the eclipse day, although it was clear in the morning and noon, the eclipse was clouded out in the afternoon, and it rained heavily in the evening. The observation was not successful.

Another team consisted of 6 people, with Yu Qingsong being the leader, and Chen Zungui, Zou Yixin, Wei Xueren, Shen Xuan and Feng Jian, going to Hokkaido, Japan. The team departed from Nanjing on June 3, arrived in Tokyo on the night of June 8, went to Hokkaido the next day, and arrived at the town of Esashi at noon on June 11. The town also received many foreign scientists during another total solar eclipse on August 9, 1896. The goals included taking images of the corona, taking films for public screening and gaining experience for observing the other total solar eclipse in 1941. There were clouds at first on eclipse day, but the sun came out of the clouds before the second contact. 3 ordinary corona images, 1 ultraviolet image and 3 sets of movies were taken.

In Nanjing, only a partial eclipse was visible. Although not worth observing compared with a total eclipse, Kao Ping-tse and Li Mingzhong who stayed in Nanjing still recorded the time of the solar eclipse, to check the accuracy of previous calculations[10][11].

Related eclipses[edit]

Solar eclipses 1935–1938[edit]

This eclipse is a member of a semester series. An eclipse in a semester series of solar eclipses repeats approximately every 177 days and 4 hours (a semester) at alternating nodes of the Moon's orbit.[12]

| Solar eclipse series sets from 1935 to 1938 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascending node | Descending node | |||

| 111 | January 5, 1935 Partial |

116 | June 30, 1935 Partial | |

| 121 | December 25, 1935 Annular |

126 | June 19, 1936 Total | |

| 131 | December 13, 1936 Annular |

136 | June 8, 1937 Total | |

| 141 | December 2, 1937 Annular |

146 | May 29, 1938 Total | |

| 151 | November 21, 1938 Partial | |||

Saros 126[edit]

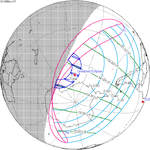

It is a part of Saros cycle 126, repeating every 18 years, 11 days, containing 72 events. The series started with partial solar eclipse on March 10, 1179. It contains annular eclipses from June 4, 1323 through April 4, 1810, hybrid eclipses from April 14, 1828 through May 6, 1864 and total eclipses from May 17, 1882 through August 23, 2044. The series ends at member 72 as a partial eclipse on May 3, 2459. The longest duration of central eclipse (annular or total) was 6 minutes, 30 seconds of annularity on June 26, 1359. The longest duration of totality was 2 minutes, 36 seconds on July 10, 1972. All eclipses in this series occurs at the Moon’s descending node.

| Series members 42–52 occur between 1901 and 2100 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 42 | 43 | 44 |

June 8, 1918 |

June 19, 1936 |

June 30, 1954 |

| 45 | 46 | 47 |

July 10, 1972 |

July 22, 1990 |

August 1, 2008 |

| 48 | 49 | 50 |

August 12, 2026 |

August 23, 2044 |

September 3, 2062 |

| 51 | 52 | |

September 13, 2080 |

September 25, 2098 | |

Inex series[edit]

This eclipse is a part of the long period inex cycle, repeating at alternating nodes, every 358 synodic months (≈ 10,571.95 days, or 29 years minus 20 days). Their appearance and longitude are irregular due to a lack of synchronization with the anomalistic month (period of perigee). However, groupings of 3 inex cycles (≈ 87 years minus 2 months) comes close (≈ 1,151.02 anomalistic months), so eclipses are similar in these groupings.

| Inex series members between 1901 and 2100: | ||

|---|---|---|

July 10, 1907 (Saros 125) |

June 19, 1936 (Saros 126) |

May 30, 1965 (Saros 127) |

May 10, 1994 (Saros 128) |

April 20, 2023 (Saros 129) |

March 30, 2052 (Saros 130) |

March 10, 2081 (Saros 131) |

||

Tritos series[edit]

This eclipse is a part of a tritos cycle, repeating at alternating nodes every 135 synodic months (≈ 3986.63 days, or 11 years minus 1 month). Their appearance and longitude are irregular due to a lack of synchronization with the anomalistic month (period of perigee), but groupings of 3 tritos cycles (≈ 33 years minus 3 months) come close (≈ 434.044 anomalistic months), so eclipses are similar in these groupings.

| Series members between 1901 and 2100 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

September 21, 1903 (Saros 123) |

August 21, 1914 (Saros 124) |

July 20, 1925 (Saros 125) | |

June 19, 1936 (Saros 126) |

May 20, 1947 (Saros 127) |

April 19, 1958 (Saros 128) | |

March 18, 1969 (Saros 129) |

February 16, 1980 (Saros 130) |

January 15, 1991 (Saros 131) | |

December 14, 2001 (Saros 132) |

November 13, 2012 (Saros 133) |

October 14, 2023 (Saros 134) | |

September 12, 2034 (Saros 135) |

August 12, 2045 (Saros 136) |

July 12, 2056 (Saros 137) | |

June 11, 2067 (Saros 138) |

May 11, 2078 (Saros 139) |

April 10, 2089 (Saros 140) | |

March 10, 2100 (Saros 141) |

|||

Metonic series[edit]

The metonic series repeats eclipses every 19 years (6939.69 days), lasting about 5 cycles. Eclipses occur in nearly the same calendar date. In addition, the octon subseries repeats 1/5 of that or every 3.8 years (1387.94 days).

| 22 eclipse events, progressing from north to south between April 8, 1902 and August 31, 1989: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 7–8 | January 24–25 | November 12 | August 31-September 1 | June 19–20 |

| 108 | 114 | 116 | ||

April 8, 1902 |

August 31, 1913 |

June 19, 1917 | ||

| 118 | 120 | 122 | 124 | 126 |

April 8, 1921 |

January 24, 1925 |

November 12, 1928 |

August 31, 1932 |

June 19, 1936 |

| 128 | 130 | 132 | 134 | 136 |

April 7, 1940 |

January 25, 1944 |

November 12, 1947 |

September 1, 1951 |

June 20, 1955 |

| 138 | 140 | 142 | 144 | 146 |

April 8, 1959 |

January 25, 1963 |

November 12, 1966 |

August 31, 1970 |

June 20, 1974 |

| 148 | 150 | 152 | 154 | |

April 7, 1978 |

January 25, 1982 |

November 12, 1985 |

August 31, 1989 | |

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e "What the eclipse revealed". Evening Standard. London, Greater London, England. 1936-06-19. p. 14. Retrieved 2023-10-17 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Solar Eclipse Seen Clearly By U.S. Scientists in Siberia". The Buffalo News. Buffalo, New York. 1936-06-20. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-10-17 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b М. Н. Гневышев. Свершения и тревоги Пулкова (Страницы воспоминаний). // Историко-астрономические исследования. — М., 1983. — Вып. 21. — С. 342—368. (in Russian)

- ^ Сергей Беляков (2012). "Солнечные затмения на страницах ивановской газеты «Рабочий край»" (in Russian). Естественнонаучный музейно-образовательный центр «Ивановский музей камня». Archived from the original on 8 July 2015.

- ^ О приезде в СССР иностранных астрономических экспедиций для наблюдения солнечного затмения. Протокол заседания Политбюро № 38, 3 апреля 1936 г. / В кн.: АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК В РЕШЕНИЯХ ПОЛИТБЮРО ЦК РКП(б)-ВКП(б)-КПСС. 1922—1991/ 1922—1952. М.: РОССПЭН, 2000. — 592 с. — Тир. 2000 экз. — Сост. В. Д. Есаков. (in Russian)

- ^ Субстратостат над Омском // Омская правда. — 21 июня 1936 года. (in Russian)

- ^ К. П. Станюкович. Подъем на самолете для наблюдения полного солнечного затмения 19 июня 1936 г./ Мироведение. — 1936. — Т.25. — № 5. — С. 22—25. (in Russian)

- ^ Б. П. Герасимович. О подготовке к наблюдениям полного солнечного затмения 19 июня 1936 г. / Вестник АН СССР. — № 9. — 1935. — С. 1—16. (in Russian)

- ^ "Полное солнечное затмение 19 июня 1936 года" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 9 August 2009.

- ^ a b Jiang Xiaoyuan, Wuyan (January 2004). 紫金山天文台史 (PDF) (in Chinese). Hebei University Press. ISBN 7-81028-974-8.

- ^ "《新闻调查》 19970314 寻踪日全食" (in Chinese). China Central Television. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015.

- ^ van Gent, R.H. "Solar- and Lunar-Eclipse Predictions from Antiquity to the Present". A Catalogue of Eclipse Cycles. Utrecht University. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

References[edit]

- Earth visibility chart and eclipse statistics Eclipse Predictions by Fred Espenak, NASA/GSFC

- Solar eclipse of June 19, 1936 in Russia

- Images of solar eclipse of June 19, 1936

- Map Kazakhstan Archived 2020-12-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Observing in Moscow