Ii Naomasa

Ii Naomasa | |

|---|---|

| 井伊 直政 | |

| |

| Head of Ii clan | |

| In office 1582–1602 | |

| Preceded by | Ii Naotora |

| Succeeded by | Ii Naokatsu |

| Daimyō of Takasaki | |

| In office 1590–1600 | |

| Succeeded by | Sakai Ietsugu |

| Daimyō of Sawayama | |

| In office 1600–1600 | |

| Preceded by | Ishida Mitsunari |

| Daimyō of Hikone | |

| In office 1600–1602 | |

| Preceded by | Ii Naotora |

| Succeeded by | Ii Naokatsu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 4, 1561 Tōtōmi Province, Japan |

| Died | March 24, 1602 (aged 41) Edo, Japan |

| Spouse | Tobai-in |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Unit | |

| Battles/wars |

|

Ii Naomasa (井伊 直政, March 4, 1561 – March 24, 1602) was a general under the Sengoku period daimyō, and later shōgun, Tokugawa Ieyasu.[1] He led the clan after the death of Ii Naotora. He married Tobai-in, Matsudaira Yasuchika's daughter and adopted daughter of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Ii Naomasa joined the ranks of the Tokugawa clan in the mid-1570s, rising swiftly through the ranks and became particularly famous after the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute, as he is recognized as one of the Four Guardians of the Tokugawa along with Honda Tadakatsu, Sakakibara Yasumasa, and Sakai Tadatsugu.

Ii Naomasa then eventually become the master of a sizable holding in Ōmi Province, following the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600.[1] His court title was Hyōbu-dayū.

Biography[edit]

Ii Naomasa was born in Hōda Village of Tōtōmi Province. His childhood name was Toramatsu (虎松),[citation needed] later Manchiyo (万千代).[2] His family, like the Tokugawa, had originally been retainers of the Imagawa clan, but following the death of the clan's leader, Imagawa Yoshimoto, in the Battle of Okehazama (1560), confusion and general chaos ensued. Naomasa's father, Ii Naochika, was falsely convicted of treason by Yoshimoto's paranoid successor, Imagawa Ujizane, and was subsequently killed.[citation needed]

Naomasa, then a very small child, escaped his danger. After many difficulties, Ii Naotora succeeded the Ii clan and become the guardian of Naomasa.[1] According to "Ii family biography, In 1574 Naomasa came to Ryutanji Temple for the 13th anniversary of Naochika's death. Then Naotora and Ryutanji Temple Chief Priest Nankei Zuimon, who also happen to be Naomasa's great uncle, consulted and tried to make Naomasa serve Tokugawa Ieyasu. First, in order to prevent Toramatsu from returning to Horai-ji Temple, Hiyo married Kiyokage Matsushita, a vassal of the Tokugawa clan, and adopted Toramatsu into the Matsushita clan.[3]

In 1575, Toramatsu was discovered by Ieyasu and allowed to return to the Ii clan, and changed his name to Machiyo. Furthermore, he was granted possession of Iinoya in Shizuoka, former territory of Ii clan, and was appointed as a page of Tokugawa Ieyasu after visiting him in Hamamatsu Castle.[3][1]

War against Takeda & Hōjō clan[edit]

In 1576, Naomasa fought for the first time in the battle against Takeda Katsuyori's forces at Shibahara (芝原) in Tōtōmi Province. Since then Naomasa has been seen alongside Ieyasu's Hatamoto vanguards, alongside Honda Tadakatsu and Sakakibara Yasumasa.[4] At the age of 18, Naomasa participated in the Tokugawa army attack on Tanaka castle which guarded by Takeda clan general named Ichijō Nobutatsu. In this battle, Naomasa fought together with Matsudaira Ietada, Sakakibara Yasumasa, and Honda Tadakatsu as they all climbed to Tanaka castle wall and fighting Nobutatsu's soldiers.[5][6][7][8]

Later, Arthur Lindsay Sadler wrote that At the age of 19, Naomasa gained attention for his first notable performance in battle.[9] Later, at the age of 22, Naomasa perform another distinguishing military service against the Takeda clan, at Siege of Takatenjin in 1581.[10]

In 1582 March of the same year, according to the Meishō genkō-roku record, after the destruction of the Takeda clan in the Battle of Tenmokuzan, Ieyasu organized a kishōmon(blood oath) with many samurai clans that formerly were vassals of the Takeda clan assigned under the command of Tokugawa clan retainers.[11] Ieyasu Tokugawa planned to subduct the largest portions of former Takeda samurai under Naomasa's command, having consulted and reached agreement with Sakai Tadatsugu, a senior Tokugawa clan vassal. However, Ieyasu's decision garnered protest from Sakakibara Yasumasa, who went so far as to threaten Naomasa. Tadatsugu immediately defended the decision of Ieyasu in response and warned Yasumasa that if he did any harm to Naomasa, Tadatsugu would personally slaughter the Sakakibara clan; thus, Yasumasa heeded Tadatsugu and did not protest further.[12] Then Tokugawa decided assigned 70 members of former Takeda samurais from Tsuchiya clan under the command of Ii Naomasa.[13][14]

Later in June, after the Honnoji Incident, Naomasa accompanied Ieyasu on an arduous journey to escape the enemies of Nobunaga in Sakai and return to Mikawa. However, their journey was very dangerous due to the existence of "Ochimusha-gari" groups across the route.[15] [a] During this journey, Naomasa and other senior Ieyasu retainers such as Sakai Tadatsugu and Honda Tadakatsu fought their way through raids and harassment from Ochimusha-gari (Samurai hunter) outlaws during their march escorting Ieyasu, and sometimes advancing by usage of gold and silver bribes given to some of the more amenable Ochimusha-gari groups.[18] As they reached Kada, an area between Kameyama town and Iga,[19] the attacks from Ochimusha-gari finally ended as they reached the territory of Kōka ikki Jizamurai warriors who are friendly to the Tokugawa clan. The Koka ikki warriors then escorting the group while assisting them eliminating the threats of the Ochimusha-gari outlaws until they reached Iga Province, where they were further protected by samurai clans from Iga ikki which accompanied the Ieyasu group until they safely reached Mikawa.[15] The Ietada nikki journal records that the escorts of Ieyasu killed some 200 outlaws during their journey from Osaka.[20][21]

in June-October 29, the Tenshō-Jingo War triangle occurred between three The Tokugawa clan, Hōjō clan, and Uesugi clan in a contest to gain control the area of Shinano Province, Ueno region, and Kai Province, which has been vacant since the destruction of Takeda clan and the death of Oda Nobunaga. After Ieyasu returned to Mikawa, he began to leading an army of 8,000 soldiers entering Kai Province (currently Gunma Prefecture), Shinano Province, and Ueno, to annex it. However, the Hōjō clan in the Kantō region also led an army of 55,000 men and crossed the Usui Pass to invade Shinano Province.[22] Ii Naomasa were recorded has participate in this war.[23] In the middle of this conflict, Naomasa further manage to recruit more samurais formerly served various Takeda generals such as Ichijō Nobutatsu, Yamagata Masakage, Masatsune Tsuchiya, and Hara Masatane with the help of former Takeda clan retainer named Kimata morikatsu who organize the contacts of those samurais with Naomasa.[24] Aside from military service, Naomasa played diplomatic role during this conflict as he received around 41 letters from many former Takeda clan's vassals to submit to Ieyasu.[25] In the final phase of this conflict, Naomasa participated in the battle of Kurokoma,[26] where the smaller Tokugawa army manage to defeat the much larger Hōjō armies, despite being reinforced by 10,000 soldiers by Satomi clan from Awa Province (Chiba).[27] The result of this battle, combined with the defection of Sanada Masayuki to the Tokugawa side has forced the Hōjō clan to negotiate truce with Ieyasu.[28] and The Hōjō clan then sent Hōjō Ujinobu as representative, while the Tokugawa sent Naomasa as representative.[29][30]

Campaign of Komaki-Nagakute[edit]

In 1584 on April 9th, during the Battle of Nagakute, Naomasa was entrusted to lead around 3,000 soldiers on the left wing of Tokugawa forces formation.[31][32] On the opposing side, Ikeda Tsuneoki and Mori Nagayoshi commands 3,000 and 2,000 soldiers respectively.[32] At around 10 a.m., Naomasa clashed against the troops of Tsuneoki. The battle lasted over two hours, as Naomasa units repeatedly foiled attempted charges towards his position by Tsuneoki and Mori Nagayoshi troops with musket rifle barrages.[31][32], until Nagayoshi was shot and killed in action, causing the entire Tokugawa forces gained the upper hand amid chaos. Tsuneoki also killed by Nagai Naokatsu's spear and died in battle. Motosuke Ikeda was also killed by Naotsugu Ando. Meanwhile Ikeda Terumasa retreated from the battlefield. Eventually, the Tsuneoki and Mori forces were crushed, and the battle ended in victory for the Tokugawa force.[33][32] In this battle, Naomasa fought so valiantly that it elicited praise from Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who was on the opposing side.

After the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute, the front line in northern Owari reached stalemate. Ieyasu and Oda Nobukatsu led 20,000 soldiers and besieged three castles: Kanie Castle, Maeda Castle, and Shimoichiba Castle.[34] The Kanie castle were defended by Maeda Nagatane and Takigawa Kazumasu. Tadatsugu, Okanabe Mori, and Yamaguchi Shigemasa spearheading the attack towards Shimoichiba castle.[35][36] On June 22, Nobukatsu and Ieyasu launch an all-out attack on Kanie Castle. The soldiers led by Tadatsugu, While Naomasa, Ishikawa Kazumasa, Honda Tadakatsu, Sakakibara Yasumasa, and Matsudaira Ietada deployed in reserve before entering the battle with Ieyasu himself.[37] On June 23, Ieyasu entered the castle with Sakakibara Yasumasa, thus the castle were subdued. [34]

Tokugawa-Toyotomi alliance & siege of Odawara[edit]

Following the peace negotiation between Ieyasu and Hideyoshi, Hideyoshi's mother was sent to stay with Naomasa in gentle captivity, cementing an alliance between the Tokugawa and the Toyotomi.[citation needed]

In 1585, during the Tokugawa clan first siege of Ueda Castle against Sanada Masayuki, Ii Naomasa led a 5,000 soldiers reinforcement along with Osuga Yasutaka and Matsudaira Yasushige led reinforcement forces to cover the retreat of Tokugawa forces after they failed to pacify the castle due to hostile movements from Uesugi Kagekatsu.[38][39][40]

In 1586, according to "Sakakibara clan historical records", Ieyasu sent Naomasa, Honda Tadakatsu, and Sakakibara Yasumasa as representatives to Kyoto, where three of them being regarded as "Tokugawa Sanketsu"(Three great nobles of Tokugawa).[41] Then in following month, the three of them joined by Sakai Tadatsugu to accompany Ieyasu in his personal trip to Kyoto, where the four of them "became famous".[b]

In 1587, during the campaign of Toyotomi Hideyoshi against the Ikkō-ikki rebel armies, the Tokugawa clan involved in the battle of Tanaka castle in Fujieda, Shizuoka.[42]

In 1588, during a visit of Tokugawa clan to pay respect to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Naomasa were appointed to the rank of Jijū (equivalent of English Chamberlain office), and became the highest-ranking senior vassal in the Tokugawa family. This has made Naomasa outranks even the most senior Tokugawa officer such as Sakai Tadatsugu.[c]

in 1590 May, Naomasa participated in the Toyotomi forces during the campaign against the Hōjō clan. Later, as Minowa Castle surrendered without a fight, it was awarded to Ii Naomasa as castellan. Naomasa significantly expanded the castle and dug deep and wide dry moats and replaced earthen ramparts with stone walls along the main route into the castle. For the most part, this siege consisted of traditional starvation tactics. Only a few small skirmishes erupted around the castle, as when a group of miners from Kai Province dug under the castle walls, allowing men under Ii Naomasa to enter.[44]

After the surrender of the Hōjō clan, Ieyasu sent Naomasa and Sakakibara Yasumasa with 1,500 soldiers to witness the Seppuku suicide ritual procession of the defeated enemy generals, Hōjō Ujimasa and Hōjō Ujiteru.[45] As result of his meritorious service during this campaign, Naomasa were awarded with increase of domain stipends to 120,000 Koku.[46]

Suppressing rebellions in 1590-1[edit]

Later in October 28 of the same year, a massive rebellion against the Toyotomi government in Mutsu Province which incited by Hienuki Hirotada and Waga Yoshitada has broke out. In response, Hideyoshi sent a punitive expedition with 30,000 army in strength led by Ieyasu Tokugawa, Toyotomi Hidetsugu, Date Masamune, Ishida Mitsunari, Ōtani Yoshitsugu, Gamō Ujisato, Uesugi Kagekatsu, Satake Yoshishige, and Maeda Toshiie, in order to pacify those rebellions. Naomasa participated in this expedition brought in his "Red Demons" unit as vanguard of Tokugawa forces.[47]

Subsequently with Waga-Hienuki rebellion, Kunohe rebellion also broke out in March 13 1591. Thus causing the punitive expedition army to take measure of this development by splitting their forces as Ieyasu, Naomasa, Ujisato, and some commanders were now changing their focus to suppress Masazane's rebellion first.[48][49] During the operation against the Kunohe, Naomasa Ii became the vanguard with Nanbu Nobunao. As they advanced towards Kunohe castle, they faced a small forces of Kunohe rebels which easily defeated.[48] As they approached the Kunohe castle, Naomasa suggested to the other commanders to besiege the Kunohe's castle until they surrender, which met with agreement from them.[50] As the operation beint commenced, Naomasa became part of army who besieged Kunohe castle, where he and Asano Nagamasa deployed on the east side across the Nekobuchi River.[51] On 4 September, the rebels executed the prisoners inside the castle and committing mass suicide after setting fire which burned the castle for three days and three nights and killed all within.[52][48][47] After the Kunohe clan suppressed, Naomasa's detachment then rejoin the main expedition army with Mitsunari, Asano Nagamasa, and others to finish the operation of pacify Hienuki and Waga clan, as Naomasa marched across Mutsu and Dewa Province subduing the resistances and capturing castles from Waga and Hienuki's allies during his journey.

The rebellions finally being suppressed June 20 with Waga Yoshitada being slain in battle,[53] while Hienuki Hirotada sentenced to "Kaieki law" which stated that he and his clan's status and rights as samurai being stripped.[54]

Sekigahara campaign & its aftermath[edit]

In 1598 after Hideyoshi died, political strife occurred between Ieyasu with other Toyotomi clan's regents. Naomasa undertook political initiatives as he built a relationship with Kuroda Yoshitaka and Kuroda Nagamasa and forming a pact. through the Kuroda clan, Naomasa successfully swayed the other military commanders to support the Tokugawa clan.[55] On the same year, Naomasa also built Takasaki Castle and relocated his seat there. Minowa Castle was abandoned and allowed to fall into ruin.[56]

In 1600, on the eve of Sekigahara battle, Ii Naomasa troops were reinforced with a detachment of Kugai Masatoshi, vassal of Tokugawa Hidetada who at that moment still busy in the Siege of Ueda castle.[57][58]

On August 21, The Eastern army alliance which sided with Ieyasu Tokugawa attacked Takegahana castle which defended by Oda Hidenobu, who sides with Mitsunari faction.[59] They split themselves into two groups, where 18,000 soldiers led by Ikeda Terumasa and Asano Yoshinaga went to the river crossing, while 16,000 soldiers led by Naomasa, Fukushima Masanori, Hosokawa Tadaoki, Kyogoku Kochi, Kuroda Nagamasa, Katō Yoshiaki, Tōdō Takatora, Tanaka Yoshimasa, and Honda Tadakatsu went downstream at Ichinomiya.[60] The first group led by Terumasa crossed the Kiso River and engaged in a battle at Yoneno, causing the Hidenobu army routed. On the other hand, Takegahana castle were reinforced by a Western army faction's general named Sugiura Shigekatsu. The Eastern army led by Naomasa and Fukushima crossed the river and directly attacked Takegahana Castle at 9:00 AM on the August 22nd. Shigekatsu himself setting the castle on fire and committed suicide as a final act of defiance.[59]

On September 24, Ieyasu has demanded Naomasa to quickly pacify the Gifu castle, as they need to moving fast to rescue other feudal lords who sides with Ieyasu, such as Katō Sadayasu and Takenaka Shigekado, which position being besieged by Mitsunari's Western army.[d]

On September 29, Naomasa and Honda Tadakatsu led their army to rendezvous with Ikeda Terumasa army, where they engaged Oda Hidenobu army in the Battle of Gifu Castle. In this battle, Hidenobu castle were deprived the expected support from Ishikawa Sadakiyo (石川貞清), who decided to not help the Western army in this war after he made an agreement with Naomasa. Hidenobu was prepared to commit seppuku, but was persuaded by Ikeda Terumasa and others to surrender to the eastern forces, and the Gifu Castle fell.[62][63]

On October 21st, in the Battle of Sekigahara, Naomasa give a notable performance where his unit outpaced those of other generals such as Fukushima Masanori, drawing the "first blood", where Naomasa led 30 spearmens from center of formation charging the ranks of western army, followed by Masanori units who started clashing against Ukita Hideie units.[64] However, modern historian viewed that the act of Naomoasa were due to the confusions of both sides as there was heavy fogs covering the battlefield, causing him to unintentionally started the first clash against the enemy and breaking Ieyasu's order to let Masanori doing the first move in this battle.[65] As the battle entered the final phase, Naomasa turned his attention towards Shimazu troops.[66] However, Naomasa was shot and wounded by a stray bullet during his attempt to chase In his pursuit against Shimazu Yoshihiro. In the end, Naomasa lost his trails from chasing Yoshihiro, although in the process his troops also manage to kill Yoshihiro nephew named Shimazu Toyohisa.[67][68]

After the Sekigahara battle, Naomasa asking to seek pardon towards Ieyasu for Sanada Masayuki and Sanada Yukimura at the behest of Sanada Nobuyuki.[69] Naomasa also has his fief also increased from 60,000 koku into 180,000 koku.[70] Naomasa complained this to Nagai Naokatsu, as he consider it small compared to Ikeda Terumasa who received 520,000 Koku.[71] It is recorded by Arthur Lindsay Sadler that Naomasa and Honda Tadakatsu expressed dissatisfaction of their rewards to Ieyasu.[71]

Several months after the battle in Sekigahara, Naomasa sent military reinforcements to assist Yamauchi Kazutoyo pacifying rebellion in Tosa Domain against retainers of Chōsokabe clan, the Ichiryo Gusoku peasant army.[72] The wound which suffered by Naomasa in Sekigahara also prevented his personal involvement in quelling the last vestiges of the anti-Tokugawa faction in the aftermath of Sekigahara engagement.[1] Naomasa sent his vassal, Suzuki Hyōe, with force as strong as 8 ships to help Kazutoyo, which finally pacified the area in 5 weeks, after killing about 273 enemies.[73] The 273 dead rebels heads were decapitated and sent to Ii Naomasa.[74]

In 1601, Naomasa appointed to take control to Sawayama Castle in Ōmi Province, the former territory of Ishida Mitsunari,[75][3][76] However, as the castle were viewed as unstrategic in location, Naomasa ordered the castle building along with its structures dismantled, while transferring its materials instead to Kohei castle, another castle which controlled by Naomasa.[77][e]

Death[edit]

Ii Naomasa's premature death in 1602 has been widely blamed on the wound he received at Sekigahara. Naomasa was highly regarded by Tokugawa Ieyasu, so it is no surprise that his sons Naotsugu and Naotaka succeeded him in his service and title. However, Naotsugu managed to anger Ieyasu by refusing to take part in his campaign to reduce the Toyotomi clan stronghold at Osaka.

Personal Information[edit]

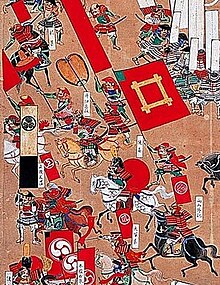

Based on the elegy Confucian scholar Oze Hoan [ja] (1564–1640), in his biographical work Taikōki, Ii Naomasa is implied has beautiful face(Bishōnen), which impressed the mother of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, during Naomasa's stay in Kyoto.[79] The "Clan records" chronicles from Edo period also stated that during the battle of Komaki-Nagakute, Naomasa were described as "beautiful and small physical stature". However, despite his unintimidating built, Naomasa fought ferociously in the Battlefield and wearing distinguishable red Armor and helmet with long horns, which rendered him a nickname 'Aka-oni'(red demon).[80]

It has also been rumored, although never confirmed, that Naomasa would sometimes wear a "monkey mask" into battle, including at Sekigahara.[citation needed]

Naomasa also known for his political astuteness, which enable him to command respect when he was tasked to lead the garrison of Minowa Castle.[81]

An anecdote from Sakakibara clan historical records has stated that among Ieyasu generals, Honda Tadakatsu excelled in bravery and Sakakibara Yasumasa excelled in leadership, while Ii Naomasa possessed both qualities.[82]

Naomasa were known as brutal disciplinarian, as he possess violent temper and easily punishes his subordinates for slightest mistakes, earning him the nickname of Hitokiri Hyōbu(Hyōbu the Manslayer/mass-murdering minister).[83] Naomasa personality even caused senior retainer like Morikatsu Kimata asked Ieyasu to be transferred into another units. while others like Hideyo Kondo and Yasumasa Ihara escape from service under Ii without Ieyasu permission, and only return during the reign of Tokugawa Hidetada[84]

According to legend, Naomasa was feared so much by his own men, that when he was critically wounded at Sekigahara, not a single one of them committed ritual seppuku, the act of honor killing to prevent a samurai from falling into enemy hands, out of fear of retaliation. As such, Naomasa was able to regain his composure and escape with his life.[citation needed]

Family[edit]

- Aunt: Jirō Hōshi

- Father: Ii Naochika

- Mother: Okuyama Hiyo (d.1585)

- Wife: Tobai-in

- Concubine: Inbu Tokuemon's daughter

- Children:

- Ii Naokatsu by Tobai-in

- Ii Naotaka by Inbu Tokuemon's daughter

- Masako married Matsudaira Tadayoshi by Tobai-in

- Koan-in married Date Hidemune by Tobai-in

Legacy[edit]

Ii Naomasa was known as the founder of Hikone Castle, after he given task by Tokugawa Ieyasu appoint him the rule of a new domain centered at Sawayama Castle. The Hikone Castle completed by his son Ii Naokatsu in 1622. The area remained under the control of Hikone Domain through the end of the Edo Period.[85] He also known as the first governor of the newly established Hikone Domain, which formed from the eastern part of Ōmi Province that formerly known as Sawayama domain which ruled by Ishida Mitsunari.[75][3] The Hikone domain which inherited through generation to descendants of Naomasa's Ii clan survived until 1871 with its last ruler from Ii clan was Ii Naonori.[86][87]

Aside from the Hikone Domain, another historical Domain founded under Naomasa's rule were Takasaki Domain, which he control for sometimes before it was transferred to Sakai Ietsugu, son of Sakai Tadatsugu.[88]

Naomasa's sets of armour are all preserved and exhibited within Hikone Castle museum, including red armor with golden horns in its helmet.[89] This kind of armor were recorded being used by Naomasa during the battle of Komaki-Nagakute.[80] Another armor which the museum preserved is the first Naomasa armor which he used during the battle of Shibahara. This kind of armor were lacking gold horns.[89]

Ii clan's Red Demons brigade[edit]

Ii Naomasa was known for his notable elite troops which nicknamed as Ii clan's Red Demons (赤鬼)(Akaoni), or Red Guards (赤備え)(akazonae).[90] The warriors which Naomasa commanded on the battlefield were notable for being outfitted almost completely in blood-red armour from their mounted samurai, bannermen, to even ashigaru. It was said for psychological impact, a tactic he adopted from Yamagata Masakage, one of Takeda Shingen's generals.[1] Constantine Nomikos Vaporis stated that the adaption of the lacquer based armor of the Japanese Samurai army has allowed the introduction of various color theme for their armor. such as Naomasa and Masakage red-clad armor units.[91]

During the Tenshō-Jingo War in 1582 between Tokugawa against the Hojo clan, Naomasa absorbed many samurai warriors from various clans that formerly served under various Takeda generals such as Ichijō Nobutatsu, Yamagata Masakage, Masatsune Tsuchiya, and Hara Masatane, into his rank. This was achieved with assistance of a former Takeda clan retainer named Kimata Morikatsu, who organize the contacts of those samurai clans with Naomasa.[92] Later, after the Tenshō-Jingo War has been ended, Tokugawa history record has stated that Naomasa further absorbed more Takeda samurai clans into his rank, after he made a blood pact (Kishômon) with 70 samurai warriors from Tsuchiya clan that formerly served Tsuchiya Masatsugu, one of Twenty-Four Generals of Takeda Shingen, to serve him as Hatamoto retainers.[13] Meanwhile, another source mentioned that total of 120 Tsuchiya clan's samurai warriors has joined Naomasa's rank instead.[3]

Aside from samurai clans, Ii Naomasa also employed Iga ninja clans from Iga Province which led by Miura Yo'emon.[93] Miura Yo'emon was reportedly entered the service of Ii clan in 1603.[94] These ninja army saw action during the Siege of Osaka under the lead of Ii Naotaka, heir of Naomasa who also given control of Ii clan's red demons after Naomasa died.[95]

Historian such as Michifumi Isoda opined that one factor why the Tokugawa clan's could conquer Japan was due to the incorporation of former Takeda clan's vassals into its rank, including Yamagata Masakage's elite red brigade cavalry into Naomasa's command.[96]

Popular culture[edit]

In theater and other contemporary works, Naomasa is often characterized as the opposite of Ieyasu's other great general, Honda Tadakatsu. While both were fierce warriors of the Tokugawa, Tadakatsu survived countless battles without ever suffering an injury, while Naomasa is often depicted as enduring many battle wounds, but fighting through them.[citation needed]

Appendix[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ According to Imatani Akira, professor of Tsuru University, and Ishikawa Tadashi, assistant professor University of Central Florida, during Sengoku period there are emergence of particularly dangerous groups called "Ochimusha-gari" or "fallen warrior hunt" groups. these groups were decentralized peasant or Rōnin self-defense forces who operates outside the law, while in actuality they often resorted to hunt Samurais or soldiers who has been defeated in wars.[16][17][15]

- ^ However, Murayama did not mention the sobriquet of "Four Guardians" here. He only mention that those four Tokugawa generals "became famous[41]

- ^ Noda Hiroko, member of Hikone castle museum directorate, has suspected that this is due to Naomasa being hailed from Ii clan, which status has Similar prestige with the Tokugawa clan themselves. Another reason was because Naomasa himself was a relative of Lady Tsukiyama.[43]。

- ^ The Gifu Sekigahara Battlefield Memorial Museum has preserved Ieyasu's letters including one which Ieyasu threaten Naomasa to complete the siege as fast as possible.[61]

- ^ However, modern era Japanese castle archaeologist Yoshimasa Miike theorized that the reason why Naomasa dismantled Sawayama castle and relocate its materials to Hikone was due to his concern that he could not secure the loyalty of the former Mitsunari vassals which reside in Sawayama castle.[78]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f 井伊直政 -Hatabo's Homepage Archived 2003-09-08 at archive.today

- ^ Arthur Lindsay Sadler (2014, p. 107)

- ^ a b c d e 山本博文監修 (2007). 江戸時代人物控1000. 小学館. p. 23. ISBN 978-4-09-626607-6.

- ^ Tetsuo Owada (2001). 争乱の地域史: 西遠江を中心に - Volume 4 [Regional history of conflict: Focusing on Nishiotomi - Volume 4] (in Japanese). 清文堂出版. p. 153. ISBN 9784792404956. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ ð̇Æ̇̌Þ̄ʹđ̇: Rekicho yoki (in Japanese). 1998. p. 九日圍:田中城、井伊直政歲十八. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Kajiwara Ai; Matsudaira Yoriyasu (2003). 歴朝要紀 Volume 2 (in Japanese). 神道大系編纂会. p. 田中城、井伊直政歲十八. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Kimura Takaatsu (1976). 武徳編年集成 (in Japanese). 名著出版. p. 229. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Motonao Narushima; Tadachika Kuwata; Takehisa Udagawa (1976). 改正三河後風土記 Volume 2 [Revised Mikawa Go Fudoki Volume 2] (in Japanese). 秋田書店. p. 110. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Arthur Lindsay Sadler (2014, p. 107)

- ^ 戦国武将100列伝 (in Japanese). 展望社. 2020. p. 121. ISBN 978-4885463730.

- ^ 小宮山敏和「戦国大名家臣の徳川家臣化について 戦国大名武田家家臣を事例として」『論集きんせい』26号、2004年

- ^ 岡谷繁実 (1944). 名将言行録. 岩波文庫. Vol. 6巻. 岩波書店. pp. 200–91. ISBN 9784003317365.

- ^ a b 丸島, 和洋 (2015). "土屋昌恒". In 柴辻, 俊六; 平山, 優; 黒田, 基樹; 丸島, 和洋 (eds.). 武田氏家臣団人名辞典. 東京堂出版. p. 505. ISBN 9784490108606.

- ^ 柴辻俊六「武田家臣団の解体と徳川政権」『戦国大名領の研究』名著出版、1981年

- ^ a b c Akira Imatani (1993). 天皇と天下人. 新人物往来社. pp. 152–153, 157–158, 、167. ISBN 4404020732.

Akira Imatani"Practice of attacking fallen warriors"; 2000; p.153 chapter 4

- ^ Fujiki Hisashi (2005). 刀狩り: 武器を封印した民衆 (in Japanese). 岩波書店. p. 29・30. ISBN 4004309654.

Kunio Yanagita "History of Japanese Farmers"

- ^ Kirino Sakuto (2001). 真説本能寺 (学研M文庫 R き 2-2) (in Japanese). 学研プラス. pp. 218–9. ISBN 4059010421.

Tadashi Ishikawa quote

- ^ Mitsuhisa Takayanagi (1958). 戦国戦記本能寺の変・山崎の戦 (1958年) (in Japanese). 春秋社. p. 65. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

Luís Fróis;History of Japan..; Nihon Yoso-kai Annual Report", Japanese historical materials also show that Ieyasu distributed a large amount of gold and silver to his subordinates) A certain " Ishikawa Tadashi Sosho

- ^ 藤田達生 (2005). "「神君伊賀越え」再考". 愛知県史研究. 9. 愛知県: 1–15. doi:10.24707/aichikenshikenkyu.9.0_1.

- ^ Masahiko Iwasawa (1968). "(Editorial) Regarding the original of Ietada's diary" (PDF). 東京大学史料編纂所報第2号. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- ^ Morimoto Masahiro (1999). 家康家臣の戦と日常 松平家忠日記をよむ (角川ソフィア文庫) Kindle Edition. KADOKAWA. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Masaru Hirayama (2016). "天正壬午の乱【増補改訂版】─本能寺の変と東国戦国史" [Tensho Migo Rebellion [revised and enlarged edition] - Honnoji Incident and the history of the Sengoku period in the Togoku region] (in Japanese). Ebisukosyo. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Okaya Shigezane (1967). 名将言行錄 定本 · Volume 6 (in Japanese). Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha. p. 33. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Toshikazu Komiyama (2002, p. 50~66)

- ^ Kōya Nakamura (1965). 德川家康公傳 / Tokugawa Ieyasu-kō den (in Japanese). 東照宮社務所. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Hotta Masaatsu (1917). 寛政重修諸家譜: 第4輯 [Various Kyushu clans record: Part 4] (in Japanese). Keio University: 榮進舍出版部. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ 竹井英文「“房相一和”と戦国期東国社会」(佐藤博信 編『中世東国の政治構造 中世東国論:上』(岩田書店、2007年) ISBN 978-4-87294-472-3

- ^ Masaru Hirayama (2016). 真田信之 : 父の知略に勝った決断力 (in Japanese). PHP研究所. ISBN 9784569830438. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Aida Nirō (1976). 日本古文書学の諸問題 (in Japanese). 名著出版. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ 千葉琢穂 (1989). 藤原氏族系図 6 [Fujiwara clan genealogy 6]. 展望社. p. 227. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ a b Arthur Lindsay Sadler (2014, p. 127-9)

- ^ a b c d 参謀本部 編 (1978). 日本戦史第13巻 小牧役 [Japanese War History Volume 13: Komaki Role] (in Japanese). p. 35-39. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

modern digital library edit of original edition 1908

- ^ 花見朔已 (1942). "小牧・長久手の役". 大日本戦史. 三教書院: 44.

- ^ a b Fujita Tatsuo (2006). 小牧・長久手の戦いの構造 [Structure of the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute] (in Japanese). 岩田書院. p. 107. ISBN 4-87294-422-4. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ 神谷存心 (1889). 小牧陣始末記(日本戦史材料 ; 第1巻) [The story of the end of the Komaki camp (Japanese military history materials; Volume 1)] (in Japanese). Tokyo: 武蔵吉彰. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Kimura Takaatsu. Naotoki, Tamaru (ed.). 武徳編年集成 (in Japanese). 拙修斎. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Narushima shichoku; Udagawa Takehisa; kuwata tadachika (1976). 改正三河後風土記 Volume 1 [Revised Mikawa Go Fudoki Volume 1] (in Japanese). 秋田書店. p. 197. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Shinano Historical Materials Publication Society (1977). 新編 信濃史料叢書 (in Japanese). 信濃史料刊行会. p. 302. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Hayashi Razan (1918). Honchō tsugan Volume 2 (in Japanese). Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Kazumasa Okusunoki (2012). 浜松城時代の徳川家康展 (in Japanese). Hamamatsu city centra Library. p. 13. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ a b Tetsuo Nakamura; Kazuo Murayama (1991). 徳川四天王: 精強家康軍団奮闘譜 歴史群像シリーズ22号. 学研プラス. pp. 111, 125. ISBN 4051053679.

- ^ Stephen Turnbull (2019). Tanaka 1587: Japan's Greatest Unknown Samurai Battle (From Retinue to Regiment). Helion and Company. ISBN 978-1912866496.

- ^ Noda Hiroko (2015). "徳川家康の家中序列構想―徳川一門衆としての井伊直政―" (PDF). 彦根城博物館だより (in Japanese) (111号).

- ^ Turnbull 1998, p. 241.

- ^ kuwata tadachika; yamaoka sōhachi; Army. General Staff Headquarters (1965). 日本の戦史 Volume 4 (in Japanese). Japan: 德間書店, 昭和 40-41 [1965-66]. p. 263. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ 高崎市史編さん委員会 (1968). 高崎市史 Volume 1 (in Japanese). 高崎市. p. 151. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ a b 青森県 (2004). 青森県史: 資料編. 中世, Volume 1 [Aomori Prefectural History: Documents. Middle Ages, Volume 1] (in Japanese). Aomori Prefecture History Editor Medieval Section. pp. 274, 702. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Seiji Kobayashi (1994). 秀吉権力の形成 書札礼・禁制・城郭政策 [Formation of Hideyoshi's power: Calligraphy, prohibition, and castle policy] (in Japanese). 東京大学出版会. p. 189. ISBN 9784130260596. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Iwate Prefectural Educational Research Institute (1966). 岩手県史 [Iwate Prefecture History] (in Japanese). 杜陵印刷. p. 105. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Ishidoriya Town History Compilation Committee (1979). 石鳥谷町史 上-下卷 [1-2] · Volume 1. 石鳥谷町. p. 299. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ 打越武志 (2021). 歴史絵巻打越家伝 : 楠木正家後裔/河内 (甲斐) 源氏流. デザインエッグ. p. 236. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2010). Hatamoto: Samurai Horse and Foot Guards 1540-1724. Osprey. ISBN 9781846034787.

- ^ 中央公論新社(編) (2020). 歴史と人物 Volume 11 [History and People volume 11 Interesting People Japanese History Ancient and Medieval Edition] (in Japanese). 中央公論新社(編). p. 104. ISBN 9784128001453. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Hosoi Kei (2002). 南部と奥州道中 [Nanbu and Oshu Road]. Yoshikawa Kobunkan. p. 104. ISBN 4642062068.

- ^ Noda 2007.

- ^ 日本吉 - Nippon-Kichi

- ^ Kyôto Daigaku. Jimbun kagaku Kenkyûjo. Chôsa hokoku Issues 37-38 (in Japanese). Kyôto Daigaku. Jimbun kagaku Kenkyûjo. p. 109. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Fujii Jōji (1994). 近世前期政治的主要人物の居所と行動 (in Japanese). 京都大学人文科学研究所. p. 109. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ a b 竹鼻町史編集委員会 (1999). 竹鼻の歴史 [Takehana] (in Japanese). Takehana Town History Publication Committee. pp. 30–31.

- ^ 尾西市史 通史編 · Volume 1 [Onishi City History Complete history · Volume 1] (in Japanese). 尾西市役所. 1998. p. 242. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "家康の手紙を読む 静岡家康紀行 NHK静岡 静岡家康紀行 NHK静岡放送局". nhk.or.jp (in Japanese). NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation). 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

Gifu Sekigahara Battlefield Memorial Museum Curator, Yamagata Takashi

- ^ 参謀本部 (1911), "石川貞清三成ノ陣ニ赴ク", 日本戦史. 関原役 [Japanese military history], 元真社

- ^ Mitsutoshi Takayanagi (1964). 新訂寛政重修諸家譜 6 (in Japanese). Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ James Murdoch (1996). A History of Japan Volume 2. Routledge. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-415-15416-1. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Kasaya Kazuhiko (2000). 関ヶ原合戦と近世の国制 [The Battle of Sekigahara and the Early Modern State System] (in Japanese). 思文閣出版. pp. 69–73. ISBN 4784210679. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Arthur Lindsay Sadler (2014, p. 127-9)

- ^ Sakuto Kirino (2010). 関ケ原島津退き口: 敵中突破三〇〇里 (学研新書 78 (in Japanese). 学研プラス. p. 234. ISBN 978-4054046016.

- ^ Arthur Lindsay Sadler (2009). Turnbull, Stephen (ed.). Shogun The Life of Tokugawa Ieyasu. Tuttle Publishing. p. 136. ISBN 9781462916542. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ 野田 2007, p. 典拠史料は「真田家武功口上之覚」(『真田家文書』中巻、1982年.

- ^ 川村 真二 (2014). 徳川四天王 家康に天下を取らせた男たち (in Japanese). PHP研究所. p. 54. ISBN 978-4569761930.

- ^ a b Arthur Lindsay Sadler (2011). Japanese Tea Ceremony Cha-No-Yu. Tuttle Publishing. p. https://www.google.co.id/books/edition/Japanese_Tea_Ceremony/pS_RAgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=ii+naomasa+sekigahara&pg=PT291&printsec=frontcover. ISBN 9781462903597. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Constantine Nomikos Vaporis Ph.D. (2019, p. 79)

- ^ Constantine Nomikos Vaporis Ph.D. (2019, p. 370)

- ^ John Whitney Hall (8 March 2015). Marius B. Jansen, Marius B. Jansen (ed.). Studies in the Institutional History of Early Modern Japan. Princeton University Press. pp. 117–8. ISBN 9781400868957. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b 村川

- ^ 井伊達夫 (2007). 井伊軍志 (新装版 ed.). 宮帯出版社. p. 107.

- ^ The Virginia Review of Asian Studies Volume 9. Virginia Consortium of Asian Studies. 2006. p. 220. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ 三池純正 (2009). 義に生きたもう一人の武将 (石田三成). 宮帯出版社. pp. 267-8.

- ^ Hoan, Oze (1626). – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Arai Shiraishi (1967). 新編 藩翰譜 第一巻 Arai Shiraishi (1657-1725) (in Japanese). Tokyo: 人物往来社. p. 458. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ なかむら, p. 126.

- ^ 中川昌久. 武備神木抄. 内閣文庫和書和書(多聞櫓文書を除く). Retrieved 5 May 2024.

Acceptable: CC0 (CC0 1.0 Worldwide Public domain provided)

- ^ Shinji Kawamura (2014). 徳川四天王 家康に天下を取らせた男たち (in Japanese). PHP研究所. p. 286. ISBN 9784569761930. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ 小宮山敏和「井伊直政家臣団の形成と徳川家中での地位」(初出:『学習院史学』40号(2002年)/所収:小宮山『譜代大名の創出と幕藩体制』(吉川弘文館、2015年) ISBN 978-4-642-03468-5)

- ^ Isomura, Yukio; Sakai, Hideya (2012). (国指定史跡事典) National Historic Site Encyclopedia. 学生社. ISBN 4311750404.(in Japanese)

- ^ Mass, Jeffrey P. and William B. Hauser. (1987). The Bakufu in Japanese History, p. 150.

- ^ Elison, George and Bardwell L. Smith (1987). Warlords, Artists, & Commoners: Japan in the Sixteenth Century, p. 18.

- ^ "朝日日本歴史人物事典". DIGITALIO.

- ^ a b Ii Hikone Museum.

- ^ kazutoshi harada; Metropolitan Museum of Art (2009). Ogawa, Morihiro (ed.). Art of the Samurai Japanese Arms and Armor, 1156-1868. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 80. ISBN 9781588393456. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ Constantine Nomikos Vaporis Ph.D. (2019, p. 22)

- ^ Toshikazu Komiyama (2002, p. 50~66)

- ^ Stephen Turnbull (2008, p. 55)

- ^ Stephen Turnbull (2012, p. 48)

- ^ Stephen Turnbull (2008, p. 55)

- ^ Michifumi Isoda (2023). 家康の誤算: 「神君の仕組み」の創造と崩壊 (in Japanese). 株式会社PHP研究所. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

Bibliography[edit]

- Arthur Lindsay Sadler (2014). The Maker of Modern Japan The Life of Tokugawa Ieyasu. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781136924705. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- Constantine Nomikos Vaporis Ph.D. (2019). Samurai An Encyclopedia of Japan's Cultured Warriors. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9781440842719. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- 村川浩平 (2013). "天正・文禄・慶長期、武家叙任と豊臣姓下賜の事例" (PDF). 駒沢史学. 80.

- Motomaro Nakamura; Fusai Nakamura (1951). Ii Naomasa/Naotaka. 彦根史談会.

- Noda, Hiroko (2007). "徳川家康天下掌握過程における井伊直政の役割" [The role of Ii Naomasa in the process of Tokugawa Ieyasu taking control of the country]. 彦根城博物館研究紀要. 18. Hikone Castle Museum.

- Turnbull, Stephen (1998). The Samurai Sourcebook. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 9781854095237.

- Stephen Turnbull (2008). Ninja (in Indonesian). Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. p. 55. ISBN 9789799101242. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- Stephen Turnbull (2012). Ninja AD 1460–1650. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781782002567. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- 野田浩子 (2017). 井伊直政: 家康筆頭家臣への軌跡 [Naomasa Ii: His path to becoming Ieyasu's top vassal]. Ebisukosyo Publication. ISBN 978-4-86403-262-9. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- なかむらたつお (1991). 歴史群像シリーズ22 徳川四天王 (in Japanese). 学習研究社. ISBN 978-4051053673.

- 野田, 浩子 (2007). "徳川家康天下掌握過程における井伊直政の役割". 彦根城博物館研究紀要. 18.

- Tatsuo Nakamura (1991). (知勇兼備の戦国武将の典型 井伊直政) VOL 2 [Ii Naomasa, a typical Sengoku warlord with wisdom and courage VOL 2] (in Japanese). 歴史群像シリーズ /Rekishi Gun-sho series.

- Toshikazu Komiyama (2002). 井伊直政家臣団の形成と徳川家中での地位 [Formation of Ii Naomasa's vassals and their status within the Tokugawa clan] (in Japanese). Gakushuin University Historical Society. pp. 50~66. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

External links[edit]

- "Guardians of the Tokugawa, the Ii Clan". go-centraljapan.jp/ (in English and Japanese). Central Japan Tourism Association. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- Ii Hikone Museum. "Hikone Castle Museum". ii-museum.jp (in Japanese). Kanakicho, Hikone City, Shiga Prefecture: Hikone Castle Museum. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- Ii family information (in Japanese)

- Painting and brief bio of Naomasa (in Japanese)

- Information on Naomasa, including images of his flag, battle standard, and armor (in Japanese)