Draft:Apartheid South Africa

| Submission declined on 22 July 2022 by Greenman (talk). This draft's references do not show that the subject qualifies for a Wikipedia article. In summary, the draft needs multiple published sources that are:

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

| Submission declined on 17 July 2021 by DoubleGrazing (talk). This submission is not adequately supported by reliable sources. Reliable sources are required so that information can be verified. If you need help with referencing, please see Referencing for beginners and Citing sources. This draft's references do not show that the subject qualifies for a Wikipedia article. In summary, the draft needs multiple published sources that are:

|  |

| Submission declined on 30 April 2021 by Greenman (talk). The proposed article does not have sufficient content to require an article of its own, but it could be merged into the existing article at Republic of South Africa (1961-1994). Since anyone can edit Wikipedia, you are welcome to add that information yourself. Thank you. |  |

Comment: Primary notability concern not addressed. Sources do not indicate that there was a "first republic", or that the republic ceased to exist in 1994. Greenman (talk) 19:06, 22 July 2022 (UTC)

Comment: Primary notability concern not addressed. Sources do not indicate that there was a "first republic", or that the republic ceased to exist in 1994. Greenman (talk) 19:06, 22 July 2022 (UTC)

Comment: 1) Firstly, the referencing is wholly inadequate: 15 citations in an article of this magnitude is nowhere near enough, leaving large parts unsupported.2) Secondly, please highlight clearly those sources which expressly discuss the concept of 'First Republic', so that the whole basis of this article can be verified, and notability established.3) Thirdly, the article is clearly unfinished, with several empty sections. DoubleGrazing (talk) 05:18, 17 July 2021 (UTC)

Comment: 1) Firstly, the referencing is wholly inadequate: 15 citations in an article of this magnitude is nowhere near enough, leaving large parts unsupported.2) Secondly, please highlight clearly those sources which expressly discuss the concept of 'First Republic', so that the whole basis of this article can be verified, and notability established.3) Thirdly, the article is clearly unfinished, with several empty sections. DoubleGrazing (talk) 05:18, 17 July 2021 (UTC)

Comment: Have you discussed with others about the basis for the article yet? Greenman (talk) 23:35, 25 May 2021 (UTC)

Comment: Have you discussed with others about the basis for the article yet? Greenman (talk) 23:35, 25 May 2021 (UTC)

Comment: The basis for this article is in question. The first line states that "The Republic of South Africa is predecessor to the present-day South Africa" which is not true - the Republic of South Africa still exists, although it did have a rather large change of government and system from 1994. I suggest first reaching consensus on Wikipedia:WikiProject South Africa and the South Africa page on where to integrate the contents here. Greenman (talk) 20:06, 30 April 2021 (UTC)

Comment: The basis for this article is in question. The first line states that "The Republic of South Africa is predecessor to the present-day South Africa" which is not true - the Republic of South Africa still exists, although it did have a rather large change of government and system from 1994. I suggest first reaching consensus on Wikipedia:WikiProject South Africa and the South Africa page on where to integrate the contents here. Greenman (talk) 20:06, 30 April 2021 (UTC)

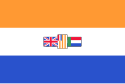

Union of South Africa (1948–1961) Republic of South Africa (1961–1994) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948–1994 | |||||||||||||

| Motto: Ex Unitate Vires (Latin for "From Unity, Strength") | |||||||||||||

| Anthem: "Die Stem van Suid-Afrika" (English: "The Call of South Africa") | |||||||||||||

Location of the Republic of South Africa until South West Africa became independent as Namibia in 1990. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Cape Town (legislative) Pretoria (administrative) Bloemfontein (judicial) Pietermaritzburg (archival) | ||||||||||||

| Largest city | Johannesburg[1][2] | ||||||||||||

| Official languages | Afrikaans English | ||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy (1948-1961) Unitary parliamentary republic (1961-1984) Unitary presidential republic (1984–1994) | ||||||||||||

| State President | |||||||||||||

• 1961–1967 (first) | C. R. Swart | ||||||||||||

• 1989–1994 (last) | F. W. de Klerk | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||

• 1961–1966 (first) | Hendrik Verwoerd | ||||||||||||

• 1978–1984 (last) | P. W. Botha | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament (1948-1984) Tricameral Parliament (1984-1994) | ||||||||||||

| Senate (dissolved 1981) | |||||||||||||

| House of Assembly | |||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Apartheid starts | 1948 | ||||||||||||

| 31 May 1961 | |||||||||||||

| 31 May 1961 | |||||||||||||

| 26 August 1966 | |||||||||||||

| 26 March 1970 | |||||||||||||

| 3 September 1984 | |||||||||||||

| 21 March 1990 | |||||||||||||

| 17 March 1992 | |||||||||||||

| 27 April 1994 | |||||||||||||

| 27 April 1994 | |||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1961 | 2,045,320 km2 (789,700 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1961 | 18,216,000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | South African Pound (1948-1961) South African rand (1961–1994) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

Apartheid South Africa, officially the Union of South Africa to 1961 and Republic of South Africa from 1961, was the former government of South Africa that existed from 1948 to 1994. The country was unified in 1910 after British Empire granted a de facto independence via South Africa Act, 1909. The republic was declared in 1961 after the referendum in favor of abandoning the Commonwealth and became a republic. It borders South Atlantic and Indian Ocean to the south; Angola (Portuguese colony before 1975), Zimbabwe (Southern Rhodesia before 1980), and Zambia (Northern Rhodesia before 1964) to the north; Swaziland (British colony before 1968) and Mozambique (Portuguese colony before 1975) in northeast; and its surrounds Lesotho (Basutoland before 1966) and Botswana (Bechuanaland before 1966).

The territory consisted of 4 British colonies that was unified into one country; Cape Colony, Natal Colony, Orange River Colony, and Transvaal Colony. The four colonies were later unified after the British Empire passed South Africa Act of 1909 which created the Union of South Africa. The colonial administration was later transferred to provincial council. South West Africa was added to the territory later after the end of First World War administrated as League of Nations Mandate.

After the Afrikaner nationalist party, National Party rise to power in 1948[3], there are subsequent rise of Anglophobia within the country among Afrikaner nationalists which support secession of South Africa from the Commonwealth. The sentiment later triggered a referendum in 1961 that reserved for Whites only, which resulted the creation of the republic with majority of Afrikaners voted yes and English South Africans voted no.[4][5][6] After the referendum; Charles Robberts Swart, who was the Governor-General at that time asked Queen Elizabeth II to dismiss him from the position of Governor-General and Swart becomes the first State President of South Africa after the parliamentary vote and was inaugurated in 31 May 1961.[7]

Johannesburg was the largest city in the country while the executive capital located in Pretoria; legislative seat in Cape Town (Second largest city after Johannesburg]]; and Bloemfontein as the judicial seat. Since its transition to republic in 1961, South Africa has been ruled by white minorities and implemented the segregationist policy called apartheid which faced nationwide and international condemnation which triggered South African Border War and Internal resistance to apartheid movement. Most of the government Executive, Legislative, and Judicial branch has been dominated by white minorities. Until 1980, South Africa was one of two African nations under white minority rule along with Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) which later was transferred to black majority rule in 1980. Namibia was given independence later in 1990, ending the 75 years of South African occupation in the region. The racial segregation policy would come to an end in 1992 with a referendum in favor of abolishing the apartheid system and the first multi-racial election was held in 1994 with Nelson Mandela as winner and first black majority president in the country.

History[edit]

Background[edit]

The beginning of South Africa can be traced by by the British Empire invasion of Dutch Cape Colony which later established the Cape Colony, British Empire would later expands further by annexing both Orange Free State and Transvaal along with Natal. Before 1909, South Africa was divided into four colonies with several failed attempt to unify the country ranging from unitary to federation form of government until the South Africa Act 1909 which gave the nominal independence for Union of South Africa with Louis Botha serving as the first Prime Minister and Viscount Gladstone as the first Governor-General. the colonial parliament replaced by provincial councils.[8] the German South West Africa was later annexed as League of Nations mandate territory from 1919 to 1990. Union of South Africa later gained its full sovereignty status after the Balfour Declaration of 1926 and Statute of Westminster 1931.

Throughout its history, South Africa has participated in both World Wars and Korean War. South Africa participated in First World War under the banner of British Empire within the Allied Power. After the end of the war, South Africe become one founding member of League of Nations after the Treaty of Versailles was signed. South Africa also participated in Second World War along with British Empire and become the member of United Nations after the end of the war. Later in 1953, South Africa participated the Korean War along with other countries under United Nations Command.

Republic Declaration[edit]

The call for republicanism has grown stronger in South Africa after the defeat of Boer Republics. After the rise of D. F. Malan and the National Party, there has been a growing republican sentiment and discontent toward The Crown rule among Afrikaner nationalists. Majority of Afrikaners who were majority group of White South Africans was in favor of cutting ties with the Commonwealth while the English who supported Jan Smuts and United Party vocally opposed the republican proposal. In 1960, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan gave addressed the nation with the Wind of Change speech in Cape Town that criticized segregation policy in South Africa. Macmillan speech later met with opposition from Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd who was a staunch supporter of segregationist policy[9]

On 5 October 1960, Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd held referendum whether South Africa should become a republic and leave the Commonwealth as the republicanism has been long term goal of the National Party. The majority of whites consist of Afrikaners voted in favor of republic with 52.29% of votes with the opposition from the English-speaking minorities who mostly concentrated in Natal Province which only gained 47.71% of the votes. The vote was also opposed and condemned by Black South Africans who was denied vote. The African National Congress viewed the referendum as one of Verwoerd's effort to strengthen the apartheid system.[10] A year after the referendum results, Governor-General Charles Robberts Swart signed the Republican Constitution and met Queen Elizabeth II in order to dismiss his position as Governor-General of South Africa.

On 31 May 1961, The Republic of South Africa was declared. Queen Elizabeth II was dismissed as head of state and the head of state role was later replaced by State President. After the republic declaration, most symbols and public holidays referencing the British monarch was changed in the process of disassociating the republic with the Crown.[11] The election of State President were later held in 10 May 1961, shortly before the transition to republic between former Governor-General Charles Robberts Swart and former Chief Justice Henry Allan Fagan which ended with Swart victory winning 66.19% of the votes. Swart were later inaugurated on the same day republic was declared as the first State President of South Africa.

Apartheid[edit]

South Africa implemented the segregationist system called apartheid that was implemented in South Africa]] and South West Africa from 1949 to 1992. The apartheid system has been implemented in 1948 after the victory of Afrikaner nationalist politician D.F. Malan in 1948 South African general election. During his tenure as Prime Minister, Malan passed several racial segregation law in order to ensure white domination in politics and economy. In 1950, Malan government signed the Population Registration Act that classify South African nationals into four racial classifications; Black, White, Coloureds (including Cape Coloureds, Cape Malays, and Chinese), and Indians (South Asians hailed from British Raj). In 1953, Malan signed the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act which segregates public services, public transports, and other premises reserved for certain races within the country. Malan also implemented the Pass laws that segregates the blacks and the whites further. The law has met further domestic resistance demanding the end of the apartheid system ranging from protests, mass strikes, and even guerilla warfare. The peaceful movement has reached its boiling point after Sharpeville massacre in front of the police station in Sharpeville township when 7,000 protesters gathered to protest against the pass law, this even marks the beginning of South Africa's departure from Commonwealth and international isolation.

After the removal of Dominion, Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd, who was staunch supporter of apartheid policy expanded the apartheid policy further calling it as "good neighbourliness policy". Due to his large role implementing apartheid policy, he was dubbed as "Architect of Apartheid". During his tenure, Verwoerd signed three legislative act;[12] Promotion of Bantu Self-government Act which marks the creation of Bantustan, Promotion of Bantu Self-government Act which allowed South African businesses to invest in Bantustan, and Extension of University Education Act which bar non-whites to enroll in certain universities. Verwoerd policies has met condemnation from the international community. The United Nations later passed the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1761 after Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld visit to Pretoria.[13] The United States and United Kingdom government implemented arms embargo as protest to the apartheid policy.[14][15][16]

Border War[edit]

End of Apartheid[edit]

Government and Politics[edit]

From 1961 to 1984, South Africa adopted Westminster model Parliamentary system. the State President were elected by the parliament while the Prime Minister was elected by election. The State President serves as ceremonial head of state and required advice from the Cabinet while the head of government position was largely held by the Prime Minister.

The legislative branch of the government was vested by the Parliament of South Africa which consist of House of Assembly and the Senate. The House of Assembly consist of 150 members and was elected for five years term with First-past-the-post voting. The vote was reserved for whites only with six members voted by White Namibians in South West Africa and four Coloureds voters from Cape Province. The assembly system has undergo several changes for three times, with the following changes were made later:

- Coloured representation was ended in 1968, leaving both the Senate and the House of Assembly representing white voters only.

- South West Africa ceased to be represented in Parliament from 1977.[17]

- The Senate was abolished in 1981, changing Parliament to a unicameral legislature

While the senate consists of eight people, consist of two representative from the provinces nominated by the state president. Four senators from South West Africa was also nominated by state president until 1977. A Coloured senator was also nominated to represent the Cape Coloureds community of the Cape Province until 1970. The senate election was jointly held with the House of Assembly election with elected senators serve five years term.

Divisions[edit]

The First Republic of South Africa were divided into four provinces with one mandate territory of South West Africa that were governed as the de-facto "fifth province" of South Africa. Each provinces were administrated by Province Administrator appointed by the central government.

| Province | Capital | Peak population | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cape of Good Hope (1910–1994) | Cape Town | 6,125,335 | |

| Natal (1910–1994) | Pietermaritzburg | 2,430,753 | |

| Orange Free State (1910–1994) | Bloemfontein | 2,193,062 | |

| Transvaal (1910–1994) | Pretoria | 9,491,265 | |

| Mandates | Capital | Peak population | Location |

| South-West Africa | Windhoek | 1,415,000 |

Bantustans[edit]

The origins of the Bantustans or “homelands” can be traced to the colonial conquest and rule which was imposed on the native Africans. Beginning with the British rulers of Natal, as well as the Cape Colony and the two Boer Republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State, the policy of the colonial administration being based on the confinement of African people to reserves or specific locations, from which they would only be able to emerge to fulfill the labour needs of the economy, originated. [18]

The first pieces of Bantustan legislation began with the Bantu Authorities Act of 1951, which gave traditional tribal authorities power within the native reserves of South Africa and made them salaried employees of the National Party government. This provided the legal basis for the potential establishment of Bantustans. The act was implemented under the leadership of Native Affairs Minister and future Prime Minister Dr. H.F. Verwoerd. The act deprived Africans of South African citizenship and separated them into false nationalities created by the South African government [19].

The Summary of the Report of the Commission for the Socio-Economic Development of the Bantu Areas within the Union of South Africa, commonly known as the Tomlinson Report, made it clear that the policy of separate development was premised on maintaining the ‘foundations on which European civilisation rests’ which ‘would vanish before the European himself disappeared in the absence of discrimination.’ [20] The entire basis of the apartheid system was focused on the maintenance of this European identity or ‘civilisation’ with warnings that dire consequences could occur if it was not ensured [21]. Following the Tomlinson Report, the 1959 Bantu Self-Government Act inaugurated a period of what was named: “grand apartheid” [22]. The act laid the foundation for the formation of the Bantustans, which were to be created based upon territorial division, the revival of chieftaincies, and separate development. The strategy of the South African government’s Bantustan program was centred on instilling ‘national unity’ and ‘national culture’ in each of the homelands, and in doing so, they attempted to forge linkages between the territories and all black South Africans. [23]. A process was later set in motion that saw four Bantustans being declared independent (Transkei, Ciskei, Venda, and Bophuthatswana) and six territories gaining limited self-determination (Gazankulu, KaNgwane, KwaNdebele, Lebowa, KwaZulu, and QwaQwa)[24].

The underdeveloped and fragmented Bantustans were frequently portrayed as being able to offer opportunities for the advancement of black people as well as being able to achieve ‘independence’. This gave a facade of legitimacy to white rule in the rest of South Africa [25]. The authority of Bantustan governments were limited and many of them were in subordination to the South African government. Major aspects of government such as finance, commerce, and security were operated by the South African government [26]. Likewise, all Bantustans relied on South Africa for 65-85% of their entire government's revenue and all senior administrative positions were held by white officials who were paid by the South African government [27]. Phatlane argues that by “introducing the concept of homeland independence, a new way of justifying the white monopoly power in the economic heartland of South Africa was being prepared... instead of justifying discrimination against blacks purely on grounds of race, it would now be done on the grounds that they were citizens of separate states” [28]. Under apartheid planning, the Bantustans experienced large economic neglect, underdevelopment, overcrowding, and forced resettlement [29]. The creation of the ethnically defined enclaves fulfilled the economic and political objectives for the apartheid government, one of which was enabling and maintaining the low-wage economy for the urban-industrial heartland of South Africa. These spaces became the sites of forced removals of established communities and their ‘dumping’ as surplus people in remote and barren rural slums. This was a product of social engineering which was a cornerstone in apartheid planning [30].

Agriculture was the primary economic activity of the Bantustans [31]. However, the main export of the Bantustans was the labour of its citizens. Able bodied males (and to a lesser extent, females) were drawn away from agriculture in the Bantustans towards employment in the designated white areas of South Africa [32]. The system of migrant labour provided the income by which citizens of Bantustans survived [33]. Furthermore, nearly all the mineral-rich parts of South Africa have been excised from the Bantustans, aside from large platinum mines in Bophuthatswana. However, mineral-rich parts of Bantustans are owned and operated by whites [34].

Decline in the national economy following international sanctions, as well as the costs related to upholding the Bantustan system placed more pressure on the government and further revealed the inherent contradictions of the policy of separate development [35]. In 1986, South African citizenship was restored to citizens of the Bantustans, which effectively ended the idea of separate development [36]. The continuing pressure faced by the apartheid system domestically and internationally, contributed towards the waning support for the apartheid policies in place, and led to the 1992 referendum on the dismantling of apartheid which white South Africans overwhelmingly voted in favour. All the Bantustans were later reincorporated back to South Africa prior to the 1994 democratic election [37].

Nominally independent Bantustans[edit]

| Bantustan | Capital | Ethnic group | Self-government years |

Nominal independence years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Umtata | Xhosa | 1963–1976 | 1976–1994 | |

| Tswana | 1972–1977 | 1977–1994 | ||

|

Venda | 1973–1979 | 1979–1994 | |

| Xhosa | 1972–1981 | 1981–1994 |

Self-governing Bantustans[edit]

| Bantustan | Capital | Tribe | Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lebowakgomo (1974–1994) Seshego (provisionally, until 1974) |

Northern Sotho (Pedi) | 1972–1994 | |

| Giyani | Tsonga (Shangaan) | 1973–1994 | |

| Phuthaditjhaba (until 1974 called Witsieshoek) | Southern Sotho | 1974–1994 | |

| Ulundi (1980–1994) Nongoma (provisionally, until 1980) |

Zulu | 1977–1994 | |

| KwaMhlanga (1986-1994) Siyabuswa (provisionally, until 1986) |

Ndebele | 1981–1994 | |

| Louieville Schoemansdal (provisionally, until the mid-1980s) |

Swazi | 1984–1994 |

Economy[edit]

South Africa have vast amount of mineral resources like old, diamond, coal, iron ore and platinum and also have very vast agricultural land. During the apartheid era, South Africa has faced multiple embargoes from the western countries, most notably the United States[38] and United Kingdom. The embargo has caused the South African manufacturers struggle to import their products overseas due to sanctions. It also caused the local business have to cater the local market in order to keep the economy running[39]

Military[edit]

Society and Culture[edit]

Censorship[edit]

The origins of the censorship of the press began in 1950 with the Suppression of Communism Act, which allowed the Minister of Justice to ban newspapers and magazines, many of which were not affiliated with the communism, but were simply against the apartheid regime.[40] Furthermore, the Minister of Justice could label people as ‘communists’ which allowed the government to restrict movement and lead to banning orders. This began the silencing of opponents of apartheid.[41]

Moreover, the South African Censorship Commission had been given authority to ban books, newspapers, and magazines. The Publications Control Board was able to ban any publication that was considered ‘undesirable.’ This mostly meant any publication may be banned if it undermined the race policy of South Africa. From 1960, more than 300 magazines and newspapers, as well as 20,000 books were suppressed by South African censorship.[42]

When the National Party came to power in 1948, the SABC began to function as a propaganda instrument for the South African government. The SABC became a government institution which was managed by Afrikaner nationalists[43] appointed by the State President[44] who instituted broadcasting policies through the lens of apartheid.[45] The SABC also controlled the radio and television programmes of the Bantustans in order to keep them within South Africa’s press censorship.[46]

The Afrikaans-language press were typically advocates of the government’s positions, while the English-language press were typically liberal opponent of apartheid.[47] The English-language press had a much better record at exposing human rights abuses than did the Afrikaans press, who never opposed the National Party or security forces in any important issue.[48] Due to this, the English-language press were frequent targets of infiltration by government agents whose goal was to disseminate disinformation and propaganda as well as spy on journalists.[49]

Censorship enormously restricted freedom of expression and freedom of press in South Africa. It was forbidden to write about the police and arrests of political prisoners; forbidden to write about the torture of detainees; forbidden to write about national security and the South African Defence Force, and following the State of Emergency in 1985, it was forbidden to quote opponents of the regime like the African National Congress.[50] Consequently, many newspapers adopted legal advisors in fear of prosecution and imprisonment.[51]

Religion[edit]

Role of Women[edit]

Education[edit]

Sport[edit]

White rule in South Africa was celebrated through international sport. Particularly through rugby, which had been frequently conceptualized as a defining demonstration of Afrikaner strength and determination. Whenever South African rugby teams would win at the international level, their victories were hailed as a justification of white rule. [52]

Most western nations were initially against racial mixing in sport, but by the late 1960s, the South African government remained the lone advocate of racial segregation, as the countries racial policies overrode the core ideology of sport being for all. Ministers of the National Party argued that interracial contact in sport would increase social stress. Acting on their assumptions, the government ordered national sports federations to separate into African, Coloured, Indian, and White associations. Non-white sportspeople were allowed to compete abroad, but only the white athletes could earn Springbok honours and only were white officials able to represent South Africa in international federations. [53]

Some sports refused to separate into racially-based federations, and over time this would later coalesce into the non-racial sports movement. On rare occasions individual white athletes would test the limits of the apartheid policy. In 1961, cricketer John Waite led a white team against a non-white team. Waite’s team included Ali Bacher, who supported the principle of merit based selection irrespective of race, and was the creator of programmes to promote cricket in African townships. In 1962, H.R. Klopper, president of the whites-only South African National Olympic Committee, rejected segregation but government pressure forced him to rescind his comment. [54]

The first reforms made in sport came in 1968 when Prime Minister Vorster allowed New Zealand to include Maori players in the teams touring South Africa. Previously Maori players were omitted from touring South Africa. In 1971, the National Party formalized a new policy. Multinationalism, a political scheme that divided South Africa into ten black ‘nations’ each with their own responsibility, including sport. This allowed black people to compete against white South Africans in ‘open international events.’ Multinationalism was seen as a very limited approach to apartheid reform. Despite its limitations, multinationalism in sport marked a turning-point in the ideology of the National Party. The South African government viewed mixed sport as something that would now ease racial conflict, not inflame it. However, the deracialization attempts by the National Party failed to end South Africa’s sporting isolation. [55]

In February 1990, State President F.W. de Klerk unbanned the African National Congress, the Communist Party of South Africa and the Pan-Africanist Congress, as well as repealed apartheid legislation as a precursor to the political negotiations that would lead to a post-apartheid South Africa.[56] However, South Africa was still not readmitted into international sport until Nelson Mandela asked the international boards of cricket, rugby, and soccer to allow for South Africa’s re-entry.[57]In 1992, the IOC invited South Africa to participate in the Olympics in Barcelona and the following year, 93 South African sports enjoyed international recognition. [58]

Sporting Boycotts[edit]

South Africa’s 1971 rugby tour of Australia led to violence and arrests which amounted between 500 and 700; a State of Emergency in the State of Queensland for 18 days; a worker’s strike by 125,000 people; and a cost of police protection which is estimated at R 11,600,000. After the end of the tour, there were calls to cancel the 1971 South African cricket tour of Australia which had come to garner more opposition than the previous rugby tour. The cricket tour was opposed by leading Australian newspapers, leading citizens, the State Governments of Western Australia and South Australia, the Council of Churches, and the Council of Trade Unions. The estimated cost of police protection for the tour would be up to R40,000,000. Following the federal Government’s refusal to back the tour, the Australian Board of Cricket Control cancelled the tour before it began.[59]

The 1973 South African rugby tour of New Zealand caused more protests from HART (Halt All Racist Tours) and CARE (Citizens’ Association for Racial Equality). Both organizations promised not to protest the tour if the South Africa team chose its players on merit rather than race, but when the South African Government refused to allow merit selection, HART and CARE began their plans to mobilize their anti-apartheid movement. New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Norman Kirk, refused to cancel the tour but withdrew government support for it. Around half of the commonwealth nations, led by the Supreme Council of Sport in Africa, threatened to boycott the 1974 Commonwealth Games being held in New Zealand if the tour went on as planned.[60] With the potential of violence threatening the tour, Prime Minister Kirk was forced to ask for the tour to be cancelled. Following an election, New Zealand’s newly elected Prime Minister, Rob Muldoon reversed the decisions made by his predecessor and a New Zealand rugby team toured South Africa in 1976. Sporting relations with South Africa was a primary topic in the 1975 New Zealand election, which Muldoon campaigned on a platform of no government interference in sports.[61] New Zealand’s subsequent rugby tour of South Africa led to a mass boycott by African nations.[62] 29 African nations departed from the 1976 Olympic Games held in Montreal as a protest of the IOC’s decision to not punish New Zealand for its sporting relation with South Africa. [63]

Demographics[edit]

Foreign Relations[edit]

Africa[edit]

Asia[edit]

The apartheid government has maintained relations with 3 Eastern Asian nations, most particularly Japan, Taiwan, and Hong Kong (British overseas territories at that time). From 1960s, the Japanese are actively trading in South Africa despite sanctions from United Nations due to its apartheid policy. This resulted Japanese are granted the honorary whites status by the apartheid government. After the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758, South African government began to pursue more friendlier relationship with Kuomintang regime in Taiwan due to its shared struggle. The good relations would later make the government to designate the trade immigrants from Taiwan honorary whites status. The government also offered South Koreans a honorary whites status, but the South Koreans government refused and denounced the apartheid system in the country.[64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72]

Western World[edit]

After South Africa severed ties with the Commonwealth, South African relationship with the western world started to sour. The government of United Kingdom denounced the apartheid system that were practiced by the government and issued arms embargo.

Use of Bantustan leaders[edit]

The South African government had portrayed the Bantustan system to both Africa and the western hemisphere as an alternative to the progressive policies advocated by liberation movements such as the prominent anti-apartheid movement, the Organisation of African Unity, and the United Nations. [73] In doing so, the government found its traditional allies in Bantustans and native reserves willing to help. Chief Buthelezi was invited by the United States Government to conduct a two month tour from April 1971 to June 1971. This was only a year after Buthelezi was installed as the chief executive officer of the Zulu “territorial authority”. Likewise, three months later in October 1971, Chiefs Matanzima, Mangope, and Buthelezi spent 3 ½ weeks in the United Kingdom as guests at the request of the British government, and thereafter two weeks in West Germany as guests of the Federal Government. Since these visits occurred, most, if not all, of the Bantustan leaders spend two to three months every year visiting the United States, the United Kingdom, West Germany, Switzerland, The Netherlands, and other Western countries. In addition to Western countries, Chief Buthelezi has also visited numerous African countries, including countries that are involved in the anti-apartheid movement, and countries that are more sympathetic to Prime Minister Vorster’s policies of dialogue and détente. [74]

The availability of Bantustan leaders to become ambassadors of South Africa’s Bantustan program created a new dimension of South Africa’s foreign policy. For the first time African spokesmen are traveling abroad to advocate for the policies of the apartheid regime, as well as being able to gain admittance in influential circles in Western nations, such as religious, commercial, financial and intellectual circles. This contrasts the South African government who had long been unable to gain credibility for its policies by conventional diplomatic methods. The spokesmen are able to garner participation in economic development for their Bantustans in these influential circles and oppose any policy which isolates South Africa on the grounds that such policies would also harm the Bantustans. [75]

International Condemnation[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ travelfilmarchive (8 November 2012). "The Union of South Africa, 1956" – via YouTube.

- ^ darren lennox (23 February 2017). "British Empire: The British Colony Of The Union Of South Africa 1956" – via YouTube.

- ^ Brian Bunting, Rise of the South African Reich, Chapter Nine, "South Africa's Nuremberg Laws"

- ^ South Africa: A War Won, Time, 9 June 1961

- ^ The Statesman's Year-Book 1975-76, J. Paxton, 1976, Macmillan, page 1289

- ^ "Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd". South African History Online. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

On 5 October 1960 a referendum was held in which White voters were asked "Do you support a republic for the Union?" — 52 percent voted 'Yes'.

- ^ South Africa & Apartheid, Robert W. Peterson, Facts on File, 1975, page 84

- ^ South Africa Act, 1909, Part V, sections 68 to 94.

- ^ The White Tribe of Africa, David Harrison, University of California Press, 1983, page 163

- ^ The Lion and the Springbok: Britain and South Africa Since the Boer War, Ronald Hyam, Peter Henshaw, Cambridge University Press, 2003, page 301

- ^ Justice of the Peace and Local Government Review, Volume 125, Justice of the Peace Limited, 1961, page 1875

- ^ "Apartheid Legislation in South Africa". Africanhistory.about.com. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ http://richardknight.homestead.com/files/armsembargo.htm

- ^ John Dugard, Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid, New York: UN Office of Legal Affairs, 2013. Accessed 26 July 2015

- ^ International Defence and Aid Fund, The Apartheid War Machine, London, 1980.

- ^ Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi, The Israeli Connection: Whom Israel arms and why, London: I B Tauris 1998, pp. 108–174 ISBN 1-85043-069-1

- ^ SOUTH AFRICA Date of Elections: 30 November 1977, Inter-Parliamentary-Union

- ^ The South African Bantustan programme: its domestic and international implications. United Nations Centre against Apartheid.

- ^ van der Merwe, Nicola S. (2017). Gambling in the Bophuthatswana Sun: Sun City and the Political Economy of a Bantustan Casino: 1965-1994 (MA). University of the Witwatersrand.

- ^ Summary of the Report of the Commission for the Socio-Economic Development of the Bantu Areas within the Union of South Africa. 1955.

- ^ Jones, Peris S. (1999). "To Come Together for Progress': Modernization and Nation-building in South Africa's Bantustan Periphery ‐ the case of Bophuthatswana". Journal of Southern African Studies. 25 (4): 583. doi:10.1080/030570799108489. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ Jensen, Steffen; Zenker, Olaf (2015). "Homelands as Frontiers: Apartheid's Loose Ends – An Introduction". Journal of Southern African Studies. 41 (5): 940. doi:10.1080/03057070.2015.1068089. S2CID 146345481. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ Jones, Peris S. (1999). "To Come Together for Progress': Modernization and Nation-building in South Africa's Bantustan Periphery ‐ the case of Bophuthatswana". Journal of Southern African Studies. 25 (4): 583. doi:10.1080/030570799108489. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ Jensen, Steffen; Zenker, Olaf (2015). "Homelands as Frontiers: Apartheid's Loose Ends – An Introduction". Journal of Southern African Studies. 41 (5): 940. doi:10.1080/03057070.2015.1068089. S2CID 146345481. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ Drummond, James H.; Rogerson, Christian M.; Drummond, Fiona J. "Adventure Tourism in the Apartheid Era: Skydiving in Mafikeng- Mmabatho". African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure: 580.

- ^ The South African Bantustan programme: its domestic and international implications. United Nations Centre against Apartheid.

- ^ The South African Bantustan programme: its domestic and international implications. United Nations Centre against Apartheid.

- ^ Phatlane, Stephens N. (2002). "The Farce of Homeland Independence: Kwa-Ndebele, the Untold Story". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 37 (3–5): 401. doi:10.1177/002190960203700308. S2CID 145418729.

- ^ Phillips, Laura (2017). "History of South Africa's Bantustans". Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of African History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.80. ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4.

- ^ Platzky, Laurine; Walker, Cherryl (1985). The Surplus People: Forced Removals in South Africa. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

- ^ The South African Bantustan programme: its domestic and international implications. United Nations Centre against Apartheid.

- ^ Kaur, Abnash (1994). "White Prosperity with Cheap Black Labour". World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues: 48.

- ^ Kaur, Abnash (1994). "White Prosperity with Cheap Black Labour". World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues: 44.

- ^ The South African Bantustan programme: its domestic and international implications. United Nations Centre against Apartheid.

- ^ King, Brian H.; McCusker, Brent (2007). "Environment and Development in the Former South African Bantustans". The Geographical Journal. 173 (1): 9. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2007.00229.x. JSTOR 30113489. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ King, Brian H. (2006). "Placing Kangwane in the New South Africa". Geographical Review. 96 (1): 82. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2006.tb00388.x. JSTOR 30034005. S2CID 153455398. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ King, Brian H.; McCusker, Brent (2007). "Environment and Development in the Former South African Bantustans". The Geographical Journal. 173 (1): 9. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2007.00229.x. JSTOR 30113489. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ^ "Sanctions Against South Africa (1986)". United States Embassy. 1986.

- ^ "South Africa's Economic History". South African Market Insights. 20 June 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Roskam, Karel (1989). 'South Africans may not know everything' (and that goes for foreigners too) – 'Zuidafrikanen mogen niet alles weten' (en buitenlanders ook niet). Netherlands Institute For Southern Africa. Omroep voor Radio Freedom.

- ^ Roskam, Karel (1989). 'South Africans may not know everything' (and that goes for foreigners too) – 'Zuidafrikanen mogen niet alles weten' (en buitenlanders ook niet). Netherlands Institute For Southern Africa. Omroep voor Radio Freedom.

- ^ Roskam, Karel (1989). 'South Africans may not know everything' (and that goes for foreigners too) – 'Zuidafrikanen mogen niet alles weten' (en buitenlanders ook niet). Netherlands Institute For Southern Africa. Omroep voor Radio Freedom.

- ^ Scharnick-Udemans, Lee-Shae S. (2018). "TV is the Devil, the Devil is on TV: Wild Religion and Wild Media in South Africa". Journal for the Study of Religion. 31 (2): 187. doi:10.17159/2413-3027/2018/v31n2a8. JSTOR 26778580.

- ^ Roskam, Karel (1989). 'South Africans may not know everything' (and that goes for foreigners too) – 'Zuidafrikanen mogen niet alles weten' (en buitenlanders ook niet). Netherlands Institute For Southern Africa. Omroep voor Radio Freedom.

- ^ Scharnick-Udemans, Lee-Shae S. (2018). "TV is the Devil, the Devil is on TV: Wild Religion and Wild Media in South Africa". Journal for the Study of Religion. 31 (2): 187. doi:10.17159/2413-3027/2018/v31n2a8. JSTOR 26778580.

- ^ Roskam, Karel (1989). 'South Africans may not know everything' (and that goes for foreigners too) – 'Zuidafrikanen mogen niet alles weten' (en buitenlanders ook niet). Netherlands Institute For Southern Africa. Omroep voor Radio Freedom.

- ^ Graybill, Lyn (2000). "Lingering Legacy: Apartheid and the South African Press". Current History. 99 (637): 227–230. doi:10.1525/curh.2000.99.637.227. JSTOR 45318448.

- ^ Graybill, Lyn (2000). "Lingering Legacy: Apartheid and the South African Press". Current History. 99 (637): 229. doi:10.1525/curh.2000.99.637.227. JSTOR 45318448.

- ^ Graybill, Lyn (2000). "Lingering Legacy: Apartheid and the South African Press". Current History. 99 (637): 228. doi:10.1525/curh.2000.99.637.227. JSTOR 45318448.

- ^ Roskam, Karel (1989). 'South Africans may not know everything' (and that goes for foreigners too) – 'Zuidafrikanen mogen niet alles weten' (en buitenlanders ook niet). Netherlands Institute For Southern Africa. Omroep voor Radio Freedom.

- ^ Roskam, Karel (1989). 'South Africans may not know everything' (and that goes for foreigners too) – 'Zuidafrikanen mogen niet alles weten' (en buitenlanders ook niet). Netherlands Institute For Southern Africa. Omroep voor Radio Freedom.

- ^ Anderson, Connie M.; Bielert, Troy A.; Jones, Ryan P. (2004). "One Country, One Sport, Endless Knowledge: The Anthropological Study of Sports in South Africa". Anthropologica. 46 (1): 47–55. doi:10.2307/25606167. JSTOR 25606167.

- ^ Booth, Douglas (2003). "Hitting Apartheid for Six? The Politics of the South African Sports Boycott". Journal of Contemporary History. 38 (3): 478. doi:10.1177/0022009403038003008. JSTOR 3180648. S2CID 145730533.

- ^ Booth, Douglas (2003). "Hitting Apartheid for Six? The Politics of the South African Sports Boycott". Journal of Contemporary History. 38 (3): 478. doi:10.1177/0022009403038003008. JSTOR 3180648. S2CID 145730533.

- ^ Booth, Douglas (2003). "Hitting Apartheid for Six? The Politics of the South African Sports Boycott". Journal of Contemporary History. 38 (3): 481. doi:10.1177/0022009403038003008. JSTOR 3180648. S2CID 145730533.

- ^ Booth, Douglas (2003). "Hitting Apartheid for Six? The Politics of the South African Sports Boycott". Journal of Contemporary History. 38 (3): 490. doi:10.1177/0022009403038003008. JSTOR 3180648. S2CID 145730533.

- ^ Anderson, Connie M.; Bielert, Troy A.; Jones, Ryan P. (2004). "One Country, One Sport, Endless Knowledge: The Anthropological Study of Sports in South Africa". Anthropologica. 46 (1): 49. doi:10.2307/25606167. JSTOR 25606167.

- ^ Booth, Douglas (2003). "Hitting Apartheid for Six? The Politics of the South African Sports Boycott". Journal of Contemporary History. 38 (3): 490. doi:10.1177/0022009403038003008. JSTOR 3180648. S2CID 145730533.

- ^ Lapik, Richard E. International Seminar on the Eradication of Apartheid and in Support of the Struggle for Liberation in South Africa: Apartheid Sport and South Africa's Foreign Policy:1976. United Nations Centre against Apartheid. p. 4.

- ^ Lapik, Richard E. International Seminar on the Eradication of Apartheid and in Support of the Struggle for Liberation in South Africa: Apartheid Sport and South Africa's Foreign Policy:1976. United Nations Centre against Apartheid. p. 4.

- ^ Lapik, Richard E. International Seminar on the Eradication of Apartheid and in Support of the Struggle for Liberation in South Africa: Apartheid Sport and South Africa's Foreign Policy:1976. United Nations Centre against Apartheid. p. 4.

- ^ Nixon, Rob (1992). "Apartheid on the Run: The South African Sports Boycott". Transition (58): 78. doi:10.2307/2934968. JSTOR 2934968.

- ^ Guttmann, Allen (1988). "The Cold War and the Olympics". International Journal. 43 (4): 559. doi:10.2307/40202563. JSTOR 40202563.

- ^ South Africa: Honorary Whites, TIME, 19 January 1962

- ^ "In South Africa, Chinese is the New Black". The Wall Street Journal. 19 June 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Gerardy, Justine (21 June 2008). "Chinese have trod murky path as 'non-people'". IOL News. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

they had to get permission right down to the neighbours

- ^ Ho, Ufrieda (24 April 2015). "Alan Ho's death stirs hope out of tragedy". The M&G Online. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

Still, a family that wanted to move into a white suburb had to ask the permission of their neighbours – 10 houses to the front, 10 to the back and 10 on each side of the house they intended to call home.

- ^ Far Eastern Economic Review, 1964, page 518

- ^ Sanctions and Honorary Whites: Diplomatic Policies and Economic Realities in Relations Between Japan and South Africa, Masako Osada, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, page 94

- ^ A Matter of Honour: Being Chinese in South Africa, Yoon Jung Park, Lexington Books, 2008 page 159

- ^ "South Korea–South Africa Relations". The Embassy of the Republic of Korea to the Republic of South Africa. 6 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ "Premier Sun visits four African countries". Taiwan Review. Government Information Office, Republic of China (Taiwan). 5 January 1980. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011.

- ^ The South African Bantustan programme: its domestic and international implications. United Nations Centre against Apartheid.

- ^ The South African Bantustan programme: its domestic and international implications. United Nations Centre against Apartheid.

- ^ The South African Bantustan programme: its domestic and international implications. United Nations Centre against Apartheid.