User:Savidan/United States v. Burr

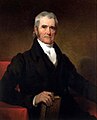

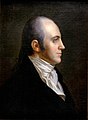

United States v. Burr was a federal criminal proceeding, from April to October 1807, against former Vice President Aaron Burr and others, on charges of treason and violations of the Neutrality Act of 1794, for their role in the Burr conspiracy. Burr was indicted and tried in the circuit court for the District of Virginia (C.C.D. Va.) before Chief Justice John Marshall and District Judge Cyrus Griffin.

The trial was a "celebrated legal contest which, with but little intermission, lasted for six months, and in which the ability, learning, ingenuity, and eloquence of counsel equalled any ever displayed in this, or possibly any other, country."[1] Specifically, the nine day argument over the meaning of the Treason Clause of Article Three was "doubtless the richest display of legal knowledge and ability of which the history of the American bar can boast."[2] According to Yoo, "[i]f the O.J. Simpson trial was the trial of this century, then the Aaron Burr case was the trial of the last."[3]

The report of the case, in twelve parts, occupies 207 octavo pages in the Federal Cases (F. Cas.). (That report is based on the notes of lawyer David Robinson.)[4] The case remains an important consitutional precedent applying the Treason Clause, the Compulsory Process Clause of the Sixth Amendment, and executive privilege under Article Two.

Dramatis personæ[edit]

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Witnesses

- Grand jurors

|

|

|

|

|

|

Background[edit]

Definition of treason[edit]

Article Three, Section Three, Clause One of the Constitution provides that:

- Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.[5]

Section 1 of the Crimes Act of 1790 provided that

- if any person or persons, owing allegiance to the United States of America, shall levy war against them, or shall adhere to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United States or elsewhere, and shall be thereof convicted, on confession in open court, or on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act of treason whereof he or they shall stand indicted, such person or persons shall be adjudged guilty of treason against the United States, and shall suffer death.[6]

In Ex parte Bollman (1807), a case concerning two other Burr conspirators, the Court held that conspiracy to wage war on the United States was not treason.[7] Further, Bollman held that the evidence against both Bollman and Swartwout was insufficient to justify pre-trial detention.[8] The prosecution of Burr relied in particular on one paragraph of the opinion in Bollman. Marshall had written:

- It is not the intention of the court to say that no individual can be guilty of this crime who has not appeared in arms against his county. On the contrary, if war be actually levied, that is, if a body of men be actually assembled for the purpose of effecting by force a treasonable purpose, all those who perform any part, however minute, or however remote from the scene of action, and who are actually leagued in the general conspiracy, are to be considered as traitors. But there must be an actual assembling of men for the treasonable purpose, to constitute a levying of war.[9]

Factual background[edit]

On November 5, 1806, U.S. Attorney for Kentucky Joseph Hamilton Daveiss—without seeking an indictment, presentment, or information—filed an affidavit with the circuit court alleging that Burr had violated the Neutrality Act and requesting that the court compell Burr to appear in the District of Kentucky.[10] The motion was denied by District Judge Harry Innes.[10]

President Jefferson addressed the Burr conspiracy in his 1806 annual message to Congress and in a January 1807 special message to Congress.[11] Burr was arrested in January 1807.[11] A grand jury in the Mississippi Territory refused to indict Burr.[11]

Burr arrived in Richmond, Virginia on March 26, 1807, under a military guard of nine men commanded by Major Nicholas Perkins.[12] He remained at the Eagle Tavern until March 30.[12]

Preliminary hearing[edit]

On March 30, 1807, Major Joseph Scott, U.S. Marshal of the District, brought Burr before Marshall at the Swan Hotel in Richmond.[13] Present in the room were: Attorney General Caesar Rodney and U.S. Attorney for Virginia George Hay, on behalf of the United States; Edmund Randolph and John Wickham, for Burr; Marshal Scott and two deputies; and some friends of Burr's counsel.[14]

The charges were treason and the violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794 by conspiring to wage war against Spain, with whom the United States was at peace.[15] The evidence against Burr at the preliminary hearing was limited to the record of the case of Ex parte Bollman—in which the affadavits of generals James Wilkinson and William Eaton implicated Burr—and the testimony of Major Perkins regarding the circumstances of Burr's arrest.[16] Hay submitted a written motion to commit Burr on the two charges.[16]

Marshall continued to the hearing until the next day at the House of Delegates chamber of the Virginia State Capitol, the site of all later proceedings.[17] Two days of argument ensued.[18] Hay opened for the United States, following by Wickham, Randolph, and Burr himself for the defense, followed by Rodney in rebuttal.[18]

On April 1, Marshall refused to require any bond on the treason charge, having already held the affadavit of General James Wilkinson to be unconstitutionally insufficient in his decision in Bollman.[4] Burr was required to post bail on the Neutrality Act charge.[4] After discussion, bail was set at $10,000.[19] After an adjournment, Burr returned with five sureties, and entered the sum into recognizance.[19] Burr's next appearance was set for May 22, at the next term of the circuit court.[19]

Grand jury[edit]

On May 22, the circuit court–now consisting of both Marshall and District Judge Cyrus Griffin—convened in the House of Delegates chamber in Richmond.[20] Hay, William Wirt, and Alexander McRae appeared for the United States; Randolph, Wickham, Benjamin Botts, and John "Jack" Baker, for Burr.[4] Luther Martin joined Burr's team on May 28; Charles Lee on August 17.[4] All of Burr's counsel served pro bono.[21] Burr himself sometimes addressed on the Court on the legal issues.[21]

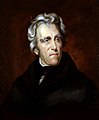

The House of Delegates chamber was packed with many spectators, including: Andrew Jackson, a voiciferous defender of Burr, and Winfield Scott.[22]

After Burr was bailed, John Wickham, one of his attorneys, invited both Burr and Marshall to a dinner.[23] Marshall reportedly did not know Burr would be in attendance until his arrival, and left the party early, but the incident was "freely used by his enemies."[23]

Selection[edit]

The Judiciary Act of 1789 provided that federal jury selection would follow the law of the forum state.[24] Contemporary Virginia law vested the sheriff of the county with unfettered discretion in choosing the 24 freeholders on a grand jury.[25] A quorum of 16 grand jurors was required.[25] If fewer than 16 grand jurors appeared, the sheriff could fill the panel out with "bystanders"—i.e. people who happened to be present at the courthouse.[25] It was not uncommon for a federal grand jury to be "on the whole more respectable than representative."[26] At least nearly all federal grand juries included at least one state or federal legislator.[26]

According to Tarter and Holt: "The most conspicuously partisan of all the grand juries during the first two decades was the one Joseph Scott summoned to Richmond in May 1807 which indicted Aaron Burr and his alleged collaborators for treason."[27] Burr's lawyers objected to the entire grand jury panel as improperly drawn.[21] This objection was overruled.[21] Burr's challenges for favor against William Branch Giles and Wilson Cary Nicholas, both Senators from Virginia, were successful.[21] Challenging a grand juror for favor was "a novel claim then and now."[28]

The impanelled grand jurors were: John Randolph of Roanoke (foreman), John Ambler, James Barbour, Munford Beverly, John Brockenbrough, Joseph C. Cabell, John W. Daniel, William Daniel, Joseph Eggleston, James M. Garnett, Thomas Harrison, John Francis Mercer, Edward Pegram, James Pleasants, Alexander Shephard, Robert Taylor, and Littleton Waller Tazewell.[29] All together, eight of the seventeen members of the grand jury would at one time serve as a U.S. Representative or Senator from Virginia or Governor of Virginia: three former Representatives (Eggleston, Mercer, and Tazewell), two current Representatives (Garnett and Randolph), two future Representatives (Pleasants and Taylor), four future Senators (Barbour, Pleasants, Randolph, and Tazewell), one former Governor (Mercer), and three future Governors (Barbour, Pleasants, and Tazewell).[29]

Marshall instructed the grand jury on the law of treason.[30] Burr requested additional instructions on the admissibility of evidence.[30] Hay promised to give notice to Burr of all evidence to be placed before the grand jury.[30]

Wirt, for the government, moved to place Burr in custody, before the grand jury proceedings began.[30] The court held that such a motion was permissible at that time and announced that it would hear evidence on the question.[30] Amid a discussion relating to the order of the presenment of evidence, Hay moved to increase Burr's bail.[30] After some fuss, Burr consented to the increase.[30]

Subpoena duces tecum[edit]

On June 9, Burr moved the court to issue a subpoena duces tecum requiring President Jefferson to produce a letter, written from General Wilkinson to him dated October 21, 1806, as well as certain army and navy orders relating to Burr.[31] Jefferson had cited this letter in his special address to Congress as evidence of Burr's guilt and as the impetus for Jefferson's calling out the militia to suppress Burr's expedition.[32] Burr hoped to use the letter both as substantive evidence of his innocence and to impeach Wilkinson.[32] More generally, the letter would "transform the treason trial into a confrontation between the judicial and executive branches" and provide Burr with an "opportunity to attack Jefferson personally."[33]

Debate on this motion consumed four or five days.[34] During the argument, Martin described the Jefferson administration as "blood hounds."[35] Wirt rebuked the court for not interrupting the defense's criticism of the administration.[34] After unsuccessfully arguing that the documents were not relevant to Burr's defense, Hay argued that a subpoena was unnecessary because the documents would be produced voluntarilly as long as some provision was made with regard to state secrets.[36] Hay read a letter from Jefferson promising "voluntarily to furnish on all occasions, whatever the purposes of justicemay require."[37]

On June 13, Marshall granted the motion, citing the Compulsory Process Clause of the Sixth Amendment and § 29 of the Crimes Act of 1790.[34] Marshall held that the president was not wholly immune to judicial process. "The propriety of introducing any paper into a case, as testimony, must depend on the character of the paper, not the character of the person who holds it."[38] Marshall suggested that the president might be immune from process if "his duties as chief magistrate demand his whole time for national objects," although he doubted that the duties were so "unremitting."[38] "The guard, furnished to this high officer, to protect him from being harassed by vexatious and unecessary subpoenas, is to be looked for in the conduct of the court after those subpoenas have issued; not in any circumstance which is to precede their being issued."[38]

Jefferson directed the Attorney General to turn over the letter ot Hay, and authorized Hay to redact the portions that were not "proper or pertinent" to Burr's defense.[39] The entire, unredacted letter was made available to the court and defense counsel.[40] Jefferson asked for clarification as to which army and navy orders were desired.[34]

A common misconception is that Marshall ordered Jefferson to personally appear and testify, and thus that Jefferson refused to comply with such an order.[33] In fact, a subpoena decus tecum, unlike a subpoena ad testificandum, requires no such appearance, and Marshall never sought Jefferson's testiomony—either in person or by deposition.[33]

Testimony of Wilkinson[edit]

General Wilkinson did not arrive in Richmond until June 14.[30] In full uniform, he was sworn and testifed on June 15.[30] Foreman Randolph was immediately hostile to Wilkinson.[41] Randolph asked the Marshall to disarm Wilkinson of his sword upon his entry.[41] At one point, Wilkinson challenged Randolph to a duel, but Randolph refused to "descend to your level."[41] Randolph later opinioned that he would not have voted for the indictment of Burr if he had known that Wilkinson would not also be charged.[41]

On June 19, Burr moved to hold attach Wilkinson for obstruction of justice for coercing the attendance of James Knox, a witness against Burr.[42] Knox had been summoned in New Orleans, and, when his willingness to appear was in doubt, ordered arrested by Judge Hall and sent to Richmand under guard.[42] The motion was denied.[42]

Indictment[edit]

At 2 pm, June 24, while the attachment motion was still being argued, the grand jury informed the Marshall that its deliberations were complete.[42] The grand jury returned two "true bills each against Burr and Harman Blennerhassett for treason and the Neutrality Act.[42] The indictment cited the December 10, 1806 meeting on Blennerhassett Island as an instance of levying war against the United States.[43]

Burr moved for bail on the ground that the indictment had been obtained by perjury.[42] The motion was denied, and the Marshall took Burr to the Richmond jail.[42] That same day, on affidavits citing Burr's health and access to counsel, the court permitted Burr to be moved to the home of Luther Martin, which was fitted with bars and locks and guarded by seven men.[41]

On June 26, returned the same true bills against Jonathan Dayton, Davis Floyd, Israel Smith, John Smith, and Comfort Tyler.[44] On June 29, the court adjourned until August 29, by which time the Marshall would have summoned a venire from Wood County (the location of Blennerhassett Island).[41] Burr was moved to a recently-constructed, three-room, third-story portion of the penitentiary.[41]

Treason trial[edit]

Petit jury selection[edit]

Arguments over the qualifications of the veniremen transpired from August 3 to August 17.[43] "Few, if any" of the Wood County venire survived challenge and the "bystanders were summoned finally."[43] On venireman, upon being excluded, said to Burr: "I know why you object to me; my given name is Alexander Hamilton."[43] The twelve petit jurors selected were: Edward Carrington, David Lambert, Richard E. Parker, Hugh Mercer, Christopher Anthony, James Sheppard, Reuben Blaky, Benjamin Franklin Graves, Miles Bott, Henry E. Coleman, John M. Sheppard, and Richard Curd.[43]

Evidence[edit]

Burr argued that the overt act of treason should be first established before the prosecution could introduce any evidence to connect Burr to the act.[43] The court denied Burr's motion.[45]

General William Eaton was the prosecution's first witness.[46] Eaton testified that Burr told him about his plan to invade Mexico, and then incite revolution in the U.S. territory west of the Allegheny Mountains.[46] Commander Thomas Truxtun took the stand next.[46] Truxtun also testified that Burr told him about his plan to invade Mexico.[46]

Jacob Albright, a laborer on Blennerhassett Island, testifed that 20 or 30 armed men assembled there on December 10, 1806 and had then fled down the river on a boat.[46] He further testified that General Tupper had attempted to arrest Blennerhassett, who had desisted only when seven or eight muskets were levelled at him.[46] Other witnesses corroborated the assembly and the flight down river, but only Albright testified to the attempted arrest of Blennerhassett.[46] Tupper himself was present in the courtroom, but not called as a witness.[46]

The prosecution indicated that it had finished presenting its evidence as to the overt act on Blennerhassett Island.[46] The proseuction admitted that Burr was not on the island, or even in Virginia, on December 10.[46]

Motion for the arrest of evidence[edit]

Burr moved to arrest the admission of evidence to connect him to the overt act on Blennerhassett Island as irrelevant, on the grounds that the overt act had not been proven in conformity with the Treason Clause.[46] "Upon it arose a great legal contest, to which all that had gone before . . . was but skirmishing."[46] Wickham spoke for almost two days, followed by Randolph.[46] Then McRae spoke for a day, followed by Wirt.[46] Wirt's argument is famous for his comparison of Blennerhassett Island to the Garden of Eden, and Burr to the temper.[46] Botts, Hay, Lee, Martin, and Randolph followed.[46] All together, the argument lasted from August 20 to August 28.[46]

On August 31, Marshall sustained the motion.[2]

Verdict[edit]

Immediately after Marshall's order, the case was submitted to the jury.[2] Within minutes, they returned the following verdict: "We, of the jury, say that Aaron Burr is not proved to be guilty under the indictment by any evidence submitted to us; we therefore find him not guilty."[2] Burr objected to the form of the verdict, but to no avail.[2]

Neutrality Act trial[edit]

The second set of indictments, for the Neutrality Act of 1794 charges, had yet to be tried.[2] Hay advised Jefferson to drop the remaining charges, but Jefferson—on the advice of Secretary of State James Madison—decided to try these charges as well, predicting that a second acquittal would further embarrass Marshall.[47] Thus, Jefferson ordered Hay to hold all the defendants and witnesses for a trial of the Neutrality Act charges.[48]

Venue for this charge was not proper against Burr in Virginia because the prosecution could not prove that any of the relevant acts occurred within the state.[2] Burr was required to post bail to ensure his appearance before the circuit court in the District of Ohio.[2]

The Neutrality Act trial began on September 3, 1807.[47] Burr moved for a second subpoena for the original copy of the October 21, 1806 letter, although he soon dropped his argument that Jefferson should be held in contempt of court for failure to provide it earlier.[47] Burr also asked for a November 12, 1806 letter, also from Wilkinson to Jefferson.[47] Hay proposed either that the court clerk should redact the letter or that Burr's counsel should inspect his redactions—"depend[ing] on their candor and integrity to make no improper disclosures"—and with the court available to resolve any dispute between cousenl.[49] Burr rejected these offers and moved to postpone the trial until the letter was provided in full.[49] Thereafter, Hay provided a version of the letter redacted by himself.[50]

On September 4, Marshall issued a second subpoena addressed to President Jefferson.[32] While this second subpoena is "overlooked" compared to the first subpoena, it had an "equally significant impact" on the questions of executive privilege and judicial supremacy.[32] In his opinion, Marshall laid out a theory of executive privilege centered on the personal privacy of the president.[51] "In no case of this kind would a court be required to proceed against the president as against an ordinary individual."[52] But, Marshall held that only the president could exercise executive privilege; in other words, Jefferson could not delegate the power to Hay.[53]

Hay returned the letter and a copy of Marshall's opinion to Jefferson.[53] On September 7, Jefferson sent Hay a redacted copy of the letter and a certificate explaining the omissions.[53] Jefferson explained that the omitted portions were irrelevant to Burr's defense and were "confidential, given for my information in the discharge of my executive functions, and which my duties & the public interest forbit me to make public."[54] Jefferson retained the original.[54] Hay turned over the redacted letter and certificate in open court, on September 9, and no further action was taken on the subpoena.[54]

As a precedent[edit]

Compulsory process[edit]

The Supreme Court has referred to Burr as the "first and most celebrated analysis" of the Compulsory Process Clause.[55] "Despite the implications of the Burr decision for federal criminal procedure, the Compulsory Process Clause rarely was a factor in this Court's decisions during the next 160 years."[56]

Executive privilege[edit]

The Supreme Court revisiting the issue of executive privilege, and discussed the nature of the holding in Burr, in United States v. Nixon (1974)[57] and Clinton v. Jones (1997).[58] Both cases quoted Marshall's admonition that no court is required to "proceed against the president as against an ordinary individual."[59] And, as the Court noted in Clinton: "We unequivocally and emphatically endorsed Marshall's position when we held that President Nixon was obligated to comply with a subpoena commanding him to produce certain tape recordings of his conversations with his aides."[60] The case remains the origin of the "modern rule that only the President can claim executive privilege."[53]

"[J]ust as the Clinton cases were merely the sequel to the Nixon cases, so too were the Nixon cases a constitutional rerun of the Aaron Burr treason trial."[61] Due to the contested nature of the Burr case in the litigation of these and other cases, "[w]hether, why, and how President Jefferson complied with this judicial order is the source of some confusion and controversy."[62] "As the first case in which a President claimed executive privilege against a court order, Burr's trial has been taken to mean different things by the different sides of the executive power/judicial supremacy debate."[62] According to Yoo, "[t]he story of the Burr trial, however, is not so simple and does not stand as a rock-solid precedent for either side."[63]

Analysis[edit]

Views on Burr's guilt[edit]

"Historians still are not sure whether Burr actually intended only to lead an attack upon the Spanish, or whether he held the more treasonous motive of separating the Western states from the Union."[64] Walter McCaleb argues that Burr intended only to attack Spain, not committ treason.[65] Thomas Abernethy argues that Burr did plot treason.[66] Forrest McDonald and Yoo argue that Burr flirted with treason but eventually decided only to attack Spain.[67]

Evaluations of Marshall's judging[edit]

Scholars have long criticized Marshall's decision in Burr as political rather than principled and as inconsistent with his decision in Ex parte Bollman (1807).[68] This "prevailing belief was most cogently spelled out, if not originated, by" Professor Edward Samuel Corwin in 1919.[69] Yoo also notes the disparity between Bollman—which stated that a traitor need not be present at the site of the treasonous mobilization—and Burr—which halted the government's presentation of evidence against Burr because he could not be placed at Blennerhassett Island.[48] Merrill D. Peterson attributes this discrepancy to bias on Marshall's part.[70]

Others defend Marshall. Faulkner concludes, "with some irony, Marshall did display a kind of bias during the trial of Burr, but it was only a prudent bias toward the popular clamor and toward Jefferson. But even this conciliation of the public was limited by Marshall's devotion to justice as he understood it: protection with 'liberality and tenderness' of the rights of the accused."[71]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Henry, 1897, at 485–86.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Henry, 1897, at 499.

- ^ Yoo, 1998, at 1439.

- ^ a b c d e Henry, 1897, at 486.

- ^ U.S. Const. art. III, § 3, cl. 1.

- ^ Crimes Act of 1790, § 1, 1 Stat. 112, 112.

- ^ Ex parte Bollman, 8 U.S. (4 Cranch) 75, 125–28.

- ^ Bollman, 8 U.S. at 128–35.

- ^ Bollman, 8 U.S. at 126.

- ^ a b United States v. Burr (Burr I), 25 F. Cas. 1 (C.C.D. Ky. 1806) (No. 14,692).

- ^ a b c Yoo, 1998, at 1441.

- ^ a b Brady, 1913, at 9.

- ^ Brady, 1913, at 9; Henry, 1897, at 485.

- ^ Brady, 1913, at 9–10; Henry, 1897, at 486.

- ^ Henry, 1897, at 485.

- ^ a b Brady, 1913, at 10.

- ^ Brady, 1913, at 11; Henry, 1897, at 485.

- ^ a b Brady, 1913, at 11.

- ^ a b c United States v. Burr (Burr II), 25 F. Cas. 2 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,692a).

- ^ Baker, 1912, at 13–14; Henry, 1897, at 486.

- ^ a b c d e Henry, 1897, at 491.

- ^ Baker, 1912, at 14–16.

- ^ a b Henry, 1897, at 487–88; Yoo, 1998, at 1444.

- ^ Tarter & Holt, 2007, at 261.

- ^ a b c Tarter & Holt, 2007, at 262.

- ^ a b Tarter & Holt, 2007, at 263.

- ^ Tarter & Holt, 2007, at 279.

- ^ Tarter & Holt, 2007, at 258.

- ^ a b Henry, 1897, at 491–92.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Henry, 1897, at 492.

- ^ Henry, 1897, at 493; Yoo, 1998, at 1447.

- ^ a b c d Yoo, 1998, at 1446.

- ^ a b c Yoo, 1998, at 1447. Cite error: The named reference "y1447" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Henry, 1897, at 493.

- ^ Henry, 1897, at 493; Yoo, 1998, at 1447.

- ^ Yoo, 1998, at 1448.

- ^ Yoo, 1998, at 1450.

- ^ a b c Burr V, 25 F. Cas. at 34.

- ^ Henry, 1897, at 493; Yoo, 1998, at 1456–57.

- ^ Yoo, 1998, at 1457.

- ^ a b c d e f g Henry, 1897, at 495.

- ^ a b c d e f g Henry, 1897, at 494.

- ^ a b c d e f Henry, 1897, at 497.

- ^ Henry, 1897, at 494–95.

- ^ Henry, 1897, at 497–98.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Henry, 1897, at 498.

- ^ a b c d Yoo, 1998, 1458.

- ^ a b Yoo, 1998, at 1445.

- ^ a b Yoo, 1998, at 1459.

- ^ Yoo, 1998, at 1459–60.

- ^ Yoo, 1998, at 1460–61.

- ^ Burr XI, 25 F. Cas. at 192.

- ^ a b c d Yoo, 1998, at 1462.

- ^ a b c Yoo, 1998, at 1463.

- ^ Pennsylvania v. Ritchie, 480 U.S. 39, 55 (1987).

- ^ Ritchie, 480 U.S. at 55–56.

- ^ United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 702, 707–08, 713–16 (1974).

- ^ Clinton v. Jones, 520 U.S. 681, 695, 699, 703–04 & n.39 (1997).

- ^ Clinton, 520 U.S. at 704 n.39 (quoting Nixon, 418 U.S. at 708, 715 (quoting Burr XI, 25 F. Cas. at 192)).

- ^ Clinton, 520 U.S. at 704.

- ^ Yoo, 1998, at 1436.

- ^ a b Yoo, 1998, at 1437.

- ^ Yoo, 1998, at 1438.

- ^ Yoo, 1998, at 1440.

- ^ Walter Flavious McCaleb, A New Light on Aaron Burr (1966).

- ^ Thomas P. Abernethy, The Burr Conspiracy (1968).

- ^ Forrest McDonald, The Presidency of Thomas Jefferson 110–14, 120–30 (1976); Yoo, 1998, at 1440 n.19.

- ^ Edward S. Corwin, John Marshall and the Constitution: A Chronicle of the Supreme Court 86–120 (1919).

- ^ Faulkner, 1966, at 247.

- ^ Merrill D. Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography 873 (1970).

- ^ Faulkner, 1966, at 258.

References[edit]

- Joseph Plunkett Brady, The Trial of Aaron Burr (1913). Text from Archive.Org • Google Play

- Robert K. Faulkner, John Marshall and the Burr Trial, 53 J. Am. Hist. 247 (1966).

- William Wirt Henry, The Trial of Aaron Burr, 3 Va. L. Reg. 477 (1897).

- Brent Tarter & Wythe Holt, The Apparent Political Selection of Federal Grand Juries in Virginia, 1789-1809, 49 Am. J. Legal Hist. 257 (2007).

- John C. Yoo, The First Claim: The Burr Trial, United States v. Nixon, and Presidetial Power, 83 Minn. L. Rev. 1435 (1998).

Case reports[edit]

- United States v. Burr (Burr III), 25 F. Cas. 25 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,692b)

- United States v. Burr (Burr IV), 25 F. Cas. 27 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,692c)

- United States v. Burr (Burr V), 25 F. Cas. 30 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,692d)

- United States v. Burr (Burr VI), 25 F. Cas. 38 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,692e)

- United States v. Burr (Burr VII), 25 F. Cas. 41 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,692f)

- United States v. Burr (Burr VIII), 25 F. Cas. 49 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,692g)

- United States v. Burr (Burr IX), 25 F. Cas. 52 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,692h)

- United States v. Burr (Burr X), 25 F. Cas. 55 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,693)

- United States v. Burr (Burr XI), 25 F. Cas. 187 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,694)

- United States v. Burr (Burr XII), 25 F. Cas. 201 (C.C.D. Va. 1807) (No. 14,694a)

External links[edit]