User:SashiRolls/sandbox2

Indigenous peoples and European colonization[edit]

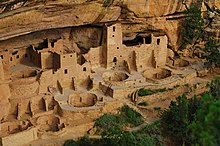

The first inhabitants of North America migrated from Siberia across the Bering land bridge at least 12,000 years ago;[1][2] the Clovis culture, which appeared around 11,000 BC, is believed to be the first widespread culture in the Americas.[3][4] Over time, indigenous North American culutures grew increasingly sophisticated, and some, such as the Mississippian culture, developed agriculture, architecture, and complex societies.[5] Indigenous peoples and cultures such as the Algonquian peoples,[6] Ancestral Puebloans,[7] and the Iroquois developed across the present-day United States.[8] Native population estimates of what is now the United States before the arrival of European immigrants range from around 500,000[9][10] to nearly 10 million.[10][11]

Christopher Columbus began exlporing the Caribbean in 1492, leading to Spanish settlements in present-day Florida and New Mexico.[12][13][14] France established their own settlements along the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico.[15] British colonization of the East Coast began with the Virginia Colony (1607) and Plymouth Colony (1620).[16][17] The Mayflower Compact and the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut established precedents for representative self-governance and constitutionalism that would develop throughout the American colonies.[18][19] While European settlers experienced conflicts with Native Americans, they also engaged in trade, exchanging European tools for food and animal pelts.[20] The native population of America declined after European arrival,[21][22][23] primarily as a result of infectious diseases brought from Europe such as smallpox and measles,[24][25] and native peoples were displaced by European expansion.[26] Colonial authorities pursued policies to force Native Americans to adopt European lifestyles,[27][28] and European settlers trafficked African slaves into the colonial United States through the Atlantic slave trade.[29]

The original Thirteen Colonies[a] were administered by Great Britain,[30] and had local governments with elections open to most white male property owners.[31][32] The colonial population grew rapidly, eclipsing Native American populations;[33] by the 1770s, the natural increase of the population was such that only a small minority of Americans had been born overseas.[34] The colonies' distance from Britain allowed for the development of self-governance,[35] and the First Great Awakening—a series of Christian revivals—fueled colonial interest in religious liberty.[36]

- ^ Erlandson, Rick & Vellanoweth 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Savage 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Waters & Stafford 2007, pp. 1122–1126.

- ^ Flannery 2015, pp. 173–185.

- ^ Lockard 2010, p. 315.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution—Handbook of North American Indians series: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15—Northeast. Bruce G. Trigger (volume editor). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. 1978 References to Indian burning for the Eastern Algonquians, Virginia Algonquians, Northern Iroquois, Huron, Mahican, and Delaware Tribes and peoples.

- ^ Fagan 2016, p. 390.

- ^ Snow, Dean R. (1994). The Iroquois. Blackwell Publishers, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55786-938-8. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ Thornton 1998, p. 34.

- ^ a b Perdue & Green 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Haines, Haines & Steckel 2000, p. 12.

- ^ Davis, Frederick T. (1932). "The Record of Ponce de Leon's Discovery of Florida, 1513". The QUARTERLY Periodical of THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY. XI (1): 5–6.

- ^ Florida Center for Instructional Technology (2002). "Pedro Menendez de Aviles Claims Florida for Spain". A Short History of Florida. University of South Florida.

- ^ "Not So Fast, Jamestown: St. Augustine Was Here First". NPR. February 28, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Petto, Christine Marie (2007). When France Was King of Cartography: The Patronage and Production of Maps in Early Modern France. Lexington Books. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7391-6247-7.

- ^ Seelye, James E. Jr.; Selby, Shawn (2018). Shaping North America: From Exploration to the American Revolution [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-4408-3669-5.

- ^ Bellah, Robert Neelly; Madsen, Richard; Sullivan, William M.; Swidler, Ann; Tipton, Steven M. (1985). Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. University of California Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-520-05388-5. OL 7708974M.

- ^ Remini 2007, pp. 2–3

- ^ Johnson 1997, pp. 26–30

- ^ Ripper, 2008 p. 6

- ^ Cook, Noble (1998). Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62730-6.

- ^ Treuer, David. "The new book 'The Other Slavery' will make you rethink American history". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ Stannard, 1993 p. xii

- ^ "The Cambridge encyclopedia of human paleopathology Archived February 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". Arthur C. Aufderheide, Conrado Rodríguez-Martín, Odin Langsjoen (1998). Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-521-55203-5

- ^ Bianchine, Russo, 1992 pp. 225–232

- ^ Joseph 2016, p. 590.

- ^ Ripper, 2008 p. 5

- ^ Calloway, 1998, p. 55

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (1997). The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440–1870. Simon and Schuster. pp. 516. ISBN 0-684-83565-7.

- ^ Bilhartz, Terry D.; Elliott, Alan C. (2007). Currents in American History: A Brief History of the United States. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1817-7.

- ^ Wood, Gordon S. (1998). The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. UNC Press Books. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-8078-4723-7.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Donald (2013). "The Right to Vote and the Rise of Democracy, 1787–1828". Journal of the Early Republic. 33 (2): 220. doi:10.1353/jer.2013.0033. S2CID 145135025.

- ^ Walton, 2009, pp. 38–39

- ^ Walton, 2009, p. 35

- ^ Otis, James (1763). The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved. ISBN 978-0-665-52678-7.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1998). The Story of American Freedom (1st ed.). W.W. Norton. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-393-04665-6.

story of American freedom.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).