User:Jdanielle92/sandbox/Sexualized Violence: Nanjing and it's survivors

Nanjing Massacres (December 13, 1937 - January 1938)[edit]

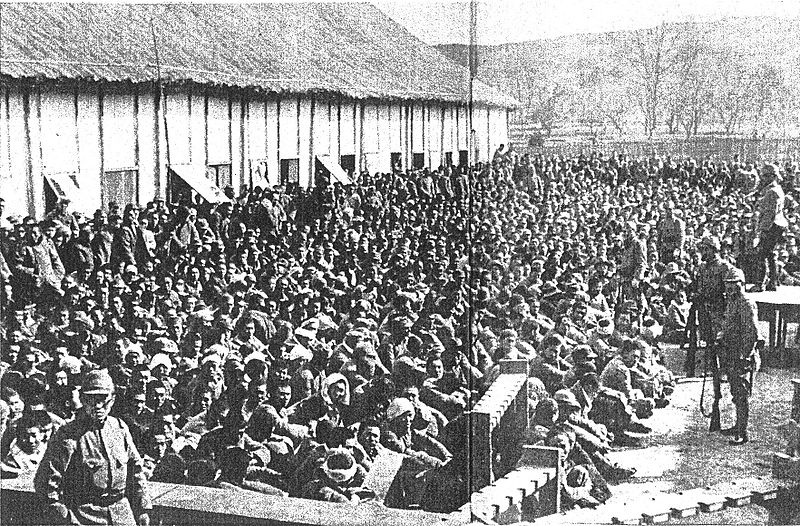

During the Second Sino-Japanese war, Japanese soldiers seized Nanjing, China. Those who were wealthy and of high stature were able to evacuate, as for the middle and low class people they were left to be subjected to mass cruelty, rape, and murder. This period in history is known as the Nanjing or Nanking Massacres. Thousands of families torn apart, people of all ages gone missing and for six weeks china endured it with no other options. Safety zones were created by American missionaries who were residing in Nanjing during the ordeal, but after a short time they too were closed down and the people of china were still subjected to harsh crimes.[2]

Sexual Violence[edit]

Used as a war tactic, war enemies often times use sexualized violence as a means to succeed in conquering territory. Sexual Violence can be defined as a sexual act or seeking sexual favors through aggression or aggravated assault. Torture, rape, kidnapping, and forced prostitution are examples of sexualized violence[3]. Sometimes these acts can even lead to automatic death or be followed by death. In the case of Nanjing, an estimated 20,000 cases of rape[4] were committed. Let alone that estimation is just based off of testimonies of those that survived their attacks or witnessed them.

Torturing[edit]

Causing harm to the masses of people this way instills fear in your enemies, that way they won't rebel against you. Fear in your enemy makes it easier to gain control or take what you want. Especially when the acts are psychologically traumatic. Based of Japanese soldier testimonies, Japanese soldiers would force citizens to watch soldiers do cruel things to their neighbors, friends, families as well as try to humiliate them just to break down their spirits and patriotism. The order of looting and destroying properties would happen with their occupants still inside to witness, just to show masculinity and power. Children were forced to watch their parents be butchered. Women and young girls were raped and bayoneted sometimes resulting in death. Nanjing citizens were dismembered, disfigured, or set a blaze.[5]

Rape and Prostitution[edit]

Sexual violence more often time resulted in Rape and the forcing of prostitution. An estimated 20,000 cases of rape were reported in trials held against japan for the take over of Nanjing. Based of testimonial accounts, Soldiers would rape men, women, and children. Women and children would go missing or taken to be forced into prostitution, placed into government sanctioned brothel like places called comfort stations[6] so that way Japanese soldiers were able to have intercourse with them. Families were forced to have incestuous relations out of humiliation as well as men were forced to have sex with the dead. Women were raped because of the needs of men before battle based off the thought that women need to care for their men.[7]

American Influence[edit]

American missionaries residing in Nanking at the time, held a neutral stature during the battle. Those who did not evacuate the city, gathered up and tried to save the lives of many refugees. Some of the more influential missionaries were that of Minnie Vautrin, John Magee, and John Rabe. Minnie Vautrin worked in a school, John Magee was a priest, and John Rabe was a german businessman who all created safety zones [8]where soldiers weren't allowed because they were american. Unfortunately the Japanese government eventually made their way into these refugee camps to recruit women for their comfort stations, to take away unclaimed men because they may have been Chinese soldiers, and eventually to its complete closure. The Japanese government attempted to close down some of the refugee camps but Minnie Vautrin, John Magee, and John Rabe fought to keep their zones open and were able to save thousands of people from rape, abuse, and murder. Minnie Vautrin housed refugees in the school in which she worked at, protecting many women and kids from being raped and sold into prostitution. John Magee pleaded with Japan to to leave his zone open where he housed thousands as well, he was able to recover proof by having someone film certain events in secrecy[9], take photos of the many people who came in injured, half way near death, or after death. All three of the missionaries recorded their daily experiences which in turn helped keep record of the events going on as well as help prosecute Japan once the wars were over.

Aftermath[edit]

With the closing of the safety camps, the Japanese was forcing the refugees back to their homes despite the broken city due to all the violence and air raids. Over time especially right after the wars commenced, the Japanese soldiers slowly evacuated the city decreasing Japanese influences. After the war, some of the officers in charge of the Japanese armies were put on trial. Many were tried and found guilty, while others were immune or weren't tried at all[10]. And although there is much evidence and witness testimonies to back of the chain of events of what happened in Nanjing, but many Japanese refused and denied that the massacre of Nanjing ever happened.

References[edit]

- ^ "Nanjing Massacre".

- ^ https://thenankingmassacre.org/2015/07/04/reference-the-new-york-times-article-18-december-1937/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Chang, Iris. The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II. New York: BasicBooks, 1997

- ^ "Nanking - Women's Media Center". Retrieved 2018-05-08.

- ^ Guttentag, Bill and Dan Sturman, directors. Nanking. ThinkFilm, 2007.

- ^ "Comfort women".

- ^ http://www.womensmediacenter.com/women-under-siege/conflicts/nanking.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Safety Zones".

- ^ "Nanking Massacre John Magee". YouTube.

- ^ https://thenankingmassacre.org/2015/07/04/nanking-war-crimes-tribunal/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Doubt". The New York Times.

External links[edit]