User:EvenBadScientistsCanObserve/sandbox

| This is a user sandbox of EvenBadScientistsCanObserve. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

Article Evaluation (2/16) - Convergent evolution[edit]

- The section on "Echolocation" should be clarified by explaining that the mutations in bats and dolphins arise at different times and thus is an example of convergent evolution

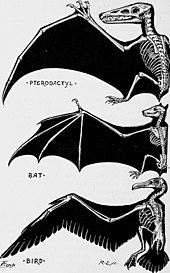

- In the opening section, the distinction is drawn between the analogy of bird and bat wings, and the forelimb which is homologous. However, in the "Flight" section, the the phrasing of the opening sentence says much the same thing but the wording suggests that it is not wings but flight which is the analogous trait. It's a subtle difference but one which should be reworded for clarity

- Again, in the "Flight" section, it is noted that the wings are functionally, but not anatomically convergent. This is another way of noting the difference between analogy and homology, but it could be more clearly noted so that it does not appear to contradict itself.

- In the section labelled "Opposable thumbs" it should be explicitly stated that the different anatomical origin of panda thumbs makes it an example of convergent evolution

- There are two sections about eyes: Eyes and Primates. The first section talks about the development of the eye, while the second section talks about the pigmentation of the eye. Would it be effective to talk about the pigmentation (or lack thereof) in the squids as well?

Flight[edit]

2/22 (added section on cerebroside content)

Birds and bats have homologous limbs because they are both ultimately derived from terrestrial tetrapods, but their flight mechanisms are only analogous, so their wings are examples of functional convergence. The two groups have powered flight, evolved independently. Their wings differ substantially in construction. The bat wing is a membrane stretched across four extremely elongated fingers and the legs. The airfoil of the bird wing is made of feathers, strongly attached to the forearm (the ulna) and the highly fused bones of the wrist and hand (the carpometacarpus), with only tiny remnants of two fingers remaining, each anchoring a single feather. So, while the wings of bats and birds are functionally convergent, they are not anatomically convergent.[1][2] Similarly, the extinct pterosaur also shows an independent evolution of vertebrate fore- and hindlimbs to wing. An even more distantly related group, the insects, have wings that evolved separately from different organs.[3]

Another similarity between birds and bats is the high concentration of cerebrosides in the epidermal layers of the wings which improves skin flexibility, a trait useful for flying animals. However, the low cerebroside content found in cutaneous lipid deposits of other mammals shows this phenomenon to have evolved separately across birds and bats making this trait an example of convergent evolution.[4]

- ^ "Homologies and analogies". University of California Berkeley. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- ^ "Plant and Animal Evolution". University of Waikato. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- ^ Alexander, David E. (2015). On the Wing: Insects, Pterosaurs, Birds, Bats and the Evolution of Animal Flight. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-19-999679-7.

- ^ Ben-Hamo, Miriam; Muñoz-Garcia, Agustí; Larrain, Paloma; Pinshow, Berry; Korine, Carmi; Williams, Joseph B. (2016-06-29). "The cutaneous lipid composition of bat wing and tail membranes: a case of convergent evolution with birds". Proc. R. Soc. B. 283 (1833): 20160636. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.0636. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 27335420.

Dissection/Article Choices (2/28)[edit]

1) Moray Eel:[edit]

I was researching this beautiful animal and I was reading about the pharyngeal jaw and now I have to research it because I have to know how it works. I have to know how it's connected to the rest of the eel so it can move so far forward and still bite down. I just really want to study this one part. Also I think they have super cute faces which is kind of weird I'm sure but hey.

Articles to modify:

- Pharyngeal jaw, just because I want to research this in more depth

- Most species pages for the Muraena genus do not exist so it may be worth doing that for the eel species we choose

- The page for Moray Eel says they have a good sense of smell. It may be interesting to explore this subject in more detail and add a section about sensory input to the page.

2) Skates:[edit]

My interest in skates has several facets. They are one of the animals on the list with which I have the least exposure (both in real life and through digital media) and so I am interested in learning more about them. The image on the page for Skate of skate movement is very interesting to me and I would be interested in exploring that. Furthermore, I vividly remember once finding a "mermaid's purse" (empty skate egg sac) washed up on a beach in the outer banks in North Carolina when I was little, and so it might be fun to explore skate reproduction because my little 6 year-old mind thought that was bonkers.

Articles to modify:

- the page for Skate (fish) is listed as a stub, so that would be worth expanding in some fashion

- Depending on which species of skate we dissect, many of the specific pages on different genera and species of skate are more or less empty, and could be filled out (no article listed because I don't know the species or genus of our specimen yet)

- There is as yet no page for synarcual (which I discovered on the rajiformes page), which could be fun to create and get some photos of one if our skate is one which has a synarcual

3) Pigeon:[edit]

The biggest reason I would want to study pigeons is because I see them all the time, but I don't know very much about them, so it would be fun to research the insides of a pigeon.

Articles to modify:

- Depending on the kind of pigeon we do, many of the articles for species of pigeon are rather incomplete. For example, the page for homing pigeon has several sections labelled incomplete, including the one for sexual dimorphisms which would be fun to contribute to.

- The page for magnetoreception is rather fleshed out, but it may be interesting to add photos or contributions to the section on pigeons, especially if we have something like a rock pigeon which makes long trips using magnetoreception as guidance.

- the page for columbidae has an extensive exploration of external anatomy, but nothing on the internal anatomy of doves. It would be interesting to provide descriptions of shared internal characteristics of the columbidae family.

Article Propositions (3/9)[edit]

- Note that group has compiled resources in Sandbox of user Anahita

Pharyngeal Jaw - adding a section either on this page or creating a new section in the page for moray eel about pharyngeal jaws. Mehta et al. (2009) is an interesting source which examines the relationship between tooth morphology on the pharyngeal jaw and diet which could be interesting to examine in detail (especially in relationship to the species we dissect). Mehta et al. (2007) has an interesting exploration of the biomechanics of the jaw opening and closing as well as the muscle groups in the area, which would be very useful for us.

Mehta, Rita S. "Ecomorphology of the Moray Bite: Relationship between Dietary Extremes and Morphological Diversity." Physiological & Biochemical Zoology, vol. 82, no. 1, Jan/Feb2009, pp. 90-103. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1086/594381.

Mehta, Rita S. and Peter C. Wainwright. "Raptorial Jaws in the Throat Help Moray Eels Swallow Large Prey." Nature, vol. 449, no. 7158, 06 Sept. 2007, pp. 79-82. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1038/nature06062. (this article is already cited on both Pharyngeal jaw and Moray eel, but I'm including it as a useful reference for later)

Mehta, Rita S. and Peter C. Wainwright. "Biting releases constraints on moray eel feeding kinematics." Journal of Experimental Biology 2007 210: 495-504; doi: 10.1242/jeb.02663

Article Draft (3/16)[edit]

Again, note that group has compiled resources in Sandbox of user Anahita

More Sources (for reference later):

Reece, Joshua S. Bowen, Brian W., Smith, David G., Larson, Allan. "Molecular phylogenetics of moray eels (Muraenidae) demonstrates multiple origins of a shell-crushing jaw (Gymnomuraena, Echidna) and multiple colonizations of the Atlantic Ocean." Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, vol. 57, no. 2, Nov 2010, pp 829-835. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.07.013

Tang, K. L., & Fielitz, C. (2013). Phylogeny of moray eels (Anguilliformes: Muraenidae), with a revised classification of true eels (Teleostei: Elopomorpha: Anguilliformes). Mitochondrial DNA: The Journal Of DNA Mapping, Sequencing & Analysis, 24(1), 55-66. doi:10.3109/19401736.2012.710226

Böhlke, E., & Randall, J. (2000). A Review of the Moray eels (Angulliformes: Muraenidae) of the Hawaiian Islands, with Descriptions of Two New Species. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 150, 203-278. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4065071

Collar, D., Reece, J., Alfaro, M., Wainwright, P., Mehta, R., Associate Editor: Dean C. Adams, & Editor: Judith L. Bronstein. (2014). Imperfect Morphological Convergence: Variable Changes in Cranial Structures Underlie Transitions to Durophagy in Moray Eels. The American Naturalist, 183(6), E168-E184. doi:10.1086/675810

Moray jaw morphology[edit]

- to be added to page Moray eel, as a subheading under the "Anatomy" section

Where most predatory fish feed using suction to pull prey into their mouths, moray eels (which show smaller pectoral structures than other teleosts) rely on biting to capture prey, using specialized jaw structures to do so.[1] In the action of lunging at prey and biting down, water flows out the posterior side of the mouth opening, reducing waves in front of the eel and allowing the eel to bite down on prey without the aid of negative pressure, with the result that bite times are greatly increased but an aggressive approach to predation is supported.[1]

The shape of the jaw also reflects the respective diets of different species of moray eel. Evolving separately multiple times across the Muraenidae, rounded jaws, and molar-like teeth allow durophagous eels like Gymnomuraena zebra, genus Echidna, and some others to consume crustaceans, while other piscivorous genera of Muraenidae have pointed jaws and longer teeth.[2][3][4] This division between durophagous and piscivorous morays is not entirely clearly defined, however, with the extent of jaw optimization for prey types being varied across different species, and bodily actions such as knotting equalizing differences in feeding ability based on jaw morphologies.[4]

- side note: The first paragraph seems too similar to a section already on the Moray eel page, and so I'm not sure it needs to be in here. However, it fits well into the themes of the section and provides useful background so I'm not positive yet if I should remove it either.

- ^ a b Mehta, Rita S.; Wainwright, Peter C. (2007-02-01). "Biting releases constraints on moray eel feeding kinematics". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (3): 495–504. doi:10.1242/jeb.02663. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 17234619.

- ^ Reece, Joshua S.; Bowen, Brian W.; Smith, David G.; Larson, Allan. "Molecular phylogenetics of moray eels (Muraenidae) demonstrates multiple origins of a shell-crushing jaw (Gymnomuraena, Echidna) and multiple colonizations of the Atlantic Ocean". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 57 (2): 829–835. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.07.013.

- ^ Mehta, Rita S. (2009-01-01). "Ecomorphology of the Moray Bite: Relationship between Dietary Extremes and Morphological Diversity". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 82 (1): 90–103. doi:10.1086/594381. ISSN 1522-2152.

{{cite journal}}: no-break space character in|first=at position 5 (help) - ^ a b Collar, David C.; Reece, Joshua S.; Alfaro, Michael E.; Wainwright, Peter C.; Mehta, Rita S. (2014-06-01). "Imperfect Morphological Convergence: Variable Changes in Cranial Structures Underlie Transitions to Durophagy in Moray Eels". The American Naturalist. 183 (6): E168–E184. doi:10.1086/675810. ISSN 0003-0147.

Feedback Responses (4/9)[edit]

- Several reviewers suggested posting my section on the page for Pharyngeal jaw. I have decided against this, for a few reasons. Other types of fish have pharyngeal jaws, although only morays are known to use their pharyngeal jaws to draw prey into their mouth and my article addition takes a teleological approach to specifically moray diets and habits. Furthermore, my article, while originally intended to discuss the pharyngeal jaw, eventually became more about the primary jaw than the pharyngeal jaw. I'll fix the title eventually

- We discussed on Tuesday a plan to dissect the eel we have, and to peel away the skin and muscle around the jaw to attempt to get a useful photo of the moray's jaw. Otherwise, I'll attempt to find a public domain drawing or diagram of the jaw to be used if a photo cannot be found.

- I have yet to decide if I will keep the first passage (about the use of the pharyngeal jaw for eating versus suction in other fish) or discard it. As mentioned in notes on my draft, this factoid is already mentioned in the article for moray eel, and since it focuses heavily on the pharyngeal jaw and my article is about the primary jaw I may scrap it. However, some of my sources do explicitly link jaw morphology to feeding style, so perhaps as a useful preface to the second passage it may need to stay if I make it fit logically. Perhaps I put it on the talk page for the moray eel, or ask the class expert if it may be prudent to rearrange the moray eel page a bit if I add this section. (side note: one reviewer suggested I edit the section that used the factoid I reuse, so I can keep my passage there. While this seems a good idea, that passage is in the center of the section on anatomy, and I fear my section focuses too much on diet and behavior, and so may warrant its own section. Again, this may be best put to the class expert)

- Many reviewers found the last sentence of my draft to be somewhat confusing, and at least one offered a useful rewording (though I fear they misconstrue my words a bit, which in itself is useful review). I will absolutely have to rework my phrasing for the purpose of improved clarity.

- I feel that I have perhaps too few sources concerning the difference in jaw shape between species, and my section lacks detail. I will do more research as I edit, of course

Article Draft #2 (4/13)[edit]

Moray jaw morphology[edit]

- to be added to page: Moray eel, as a subheading under the "Anatomy" section, with minor restructuring of paragraph in "Anatomy" that discusses use of suction vs. Pharyngeal jaw for feeding (rolling it into this section).

Where most predatory fish feed using suction to pull prey into their mouths, moray eels (which show smaller pectoral structures than other teleosts) rely on biting to capture prey, using specialized jaw structures to do so.[1] In the action of lunging at prey and biting down, water flows out the posterior side of the mouth opening, reducing waves in front of the eel and allowing the eel to bite down on prey without the aid of negative pressure, with the result that bite times are greatly increased but an aggressive approach to predation is supported.[1] In addition, The first of the five ossified branchial arches present in morays has evolved to become the pharyngeal jaw, which aids in pulling prey into the throat.[2][1]

Differing shapes of the jaw and teeth also reflect the respective diets of different species of moray eel. Evolving separately multiple times across the Muraenidae, rounded jaws, and molar-like teeth allow durophagous eels like Gymnomuraena zebra, genus Echidna, and some others to consume crustaceans, while other piscivorous genera of Muraenidae have pointed jaws and longer teeth.[3][4][5] These morphological patterns carry over to teeth positioned on the roof of the mouth, which acts as an extension of the jaw.[6][2] This division between durophagous and piscivorous morays is not entirely clearly defined, however. The extent to which jaw morphology is optimized for different prey types varies across different species, and specialized body movements such as knotting equalize morphology-predicated differences in feeding ability across different species.[5]

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Böhlke, ed. Eugenia B. (1989). Fishes of the Western North Atlantic, part 9 : Orders Anguilliformes and Saccopharyngiformes. New Haven: Sears Foundation for marine research, Yale University. ISBN 0935868453. OCLC 30092375.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:3was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

:1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ 1876-1970., Gregory, William K. (William King), (2002). Fish skulls : a study of the evolution of natural mechanisms. Malabar, Fla.: Krieger Pub. ISBN 1575242141. OCLC 48892721.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)