User:Dubyavee/WCConf

West Virginia became a state on June 20th, 1863, and consisted of 48 counties originally part of Virginia. By the end of 1863 Jefferson and Berkeley counties were also added to the new state. At the start of the war the population of these counties was//// It was the 6th most contested state with//// West Virginia was unique among the Union states for many reasons. It was the only state created as a direct result of the civil war, it was the only Union state that did not give most of its soldiers to the Union, and the only Union state containing counties that had formally voted to secede from the Union. It was also the only border state during the war which had one condidate for the highest offices at a time when the electorate was at war within itself. This comninatin of factors casued great gifficulty for the nbew state government, necessitating the presence of Union troops in the state until 1869.

Political Turmoil[edit]

With the secession of seven lower south states in 1860-1861 there was growing pressure on Virginia to join the newly formed Confederacy. Virginia governor John Letcher called for a state convention, which met on Feb. 13, 1861, with 152 delegates elected to represent Virginia's counties. [1] The 50 counties that would become the state of West Virginia had 49 delegates representing them at the convention.

The convention rejected secession until President Lincoln requested Virginia troops to help combat the southern Confederacy. On April 17 a secession ordinance was passed by a vote of 85 to 55. Delegates representing West Virginia counties voted 32 against and 13 for the ordinance, with 4 delegates absent or abstaining. The ordinance also required a public vote for final approval, to be held on May 23.

Returns from the western counties were slow in arriving when Gov. Letcher announced Virginia's passage of the secession ordinance. Some published returns were conflicting and some were missing. Historian Richard O. Curry estimated an approximate vote on the secession ordinance from West Virginia's counties as 34,677 against and 19,121 in favor of secession, with 24 counties supporting the ordinance and 26 rejecting it.[2]

Although most of West Virginia's delegates to the Richmond convention had opposed the secession ordinance the initiation of war in the west prompted most of them to return to Richmond in June for the second meeting of the convention, at which time they signed the secession ordinance, 29 of the original 49 members signing.[3]

With Virginia now part of the Confederacy a convention of Unionists in Wheeling organized a rump government on June 11, with Francis H. Pierpont as governor and a legislature composed of elected state delegates and senators who had refused to serve in the Richmond government. This "Restored Government of Virginia" was officially recognized by the Lincoln administration. The members of this government and the Wheeling convention that organized it had not been elected by the people of West Virginia for this purpose, however, and faced much opposition in the region.[4] Many of West Virginia's delegates and senators refused to join the Wheeling government and assumed their elected offices in Richmond.[5]

The extent of control by the Wheeling government was limited to the counties of the northern panhandle and the counties along the line of the B&O railroad, and depended upon the presence of the Union army in garrisoning towns and patrolling turnpikes and roads.[6][7] Historian Charles H. Ambler has said "There was no denying the fact that West Virginia was largely the creation of the Northern Panhandle and the counties along the Baltimore and Ohio railroad, which supplied her officers and funds for her public institutions."[8] The construction of the B&O railroad in the 1850's connecting Baltimore to towns in northwestern Virginia resulted in the settlement of thousands of northerners and immigrants in towns located along the railroad. In Wheeling by 1860 two of three heads-of-households were not native Virginians, and in the town of Grafton, an important hub for the railroad, about half the adult males were Irish or other immigrants.[9][10] While Grafton became a Unionist town, a short distance away secession flags flew from the courthouses of Barbour county in Philippi and Tucker county in St. George. On the Ohio river the town of Guyandotte in Cabell county raised the secession flag and began recruiting for the 8th Virginia Cavalry, while Mason County just to the north was heavily Unionist in sentiment.[11]

The May 23rd county vote on the secession ordinance was no guarantee of Union support once the war started in the west. Berkeley County, which had voted 3 to 1 against the ordinance, gave twice the number of men to the Confederate army than to the Union. Similarly, the counties of Cabell, Wayne, Putnam and others in the southwest, while voting 3 or 4 to 1 against the ordinance, gave half or nearly half their available men to the Confederate army.[12][13][14]

Partisan rangers and guerrillas were active in much of the interior of western Virginia.The Richmond government still had nominal control over counties in the southeastern section of West Virginia, with neither side able to claim many interior counties where local government had been abandoned.

Recruitment was slow for both Union and Confederate forces.[15] The Wheeling government leaned on Ohio and Pennsylvania for men to help fill the "Virginia" quotas required by the Federal government, and the Confederacy was effectively blocked from recruitment in the populous counties of the northwest by the Union army.[16][17] When Gov. Letcher called out local militias for mustering most counties in the upper northwest refused to assemble, though many in the central and southern counties responded in varying degrees.[18]

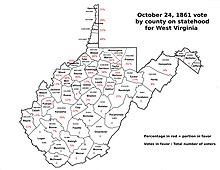

Some members of the Wheeling convention, such as John Carlile, had been demanding that western Virginia be organized as a new state and separated from Virginia. Others, such as Daniel Lamb, questioned the propriety of creating a new state and writing a constitution which included counties that could not or would not freely vote.[19] Nevertheless, the 2nd Wheeling Convention approved a statehood ordinance on August 20, with a public vote to be held of Oct. 24, 1861. The Convention was not the same as the Reorganized Government, though there were some crossover members.

The statehood vote was 18,408 in favor and and 781 against, with only 41 of the 50 counties included on the returns, 6 of which provided no votes at all. While the vote was successful in providing a referendum to offer Congress with the statehood bill, it was a failure in terms of sentiment in favor of statehood. With 79,515 voters enumerated by the 1860 census in the 50 counties the turnout was extremely low. As historian Otis K. Rice noted-"Although the Wheeling Intelligencer professed to see an "astonishing unanimity" of sentiment in the vote, in reality the returns reflected the deep division of feeling in western Virginia and intimidation on the part of supporters of the new state. Seventeen counties giving majorities for dismemberment had ratified the Virginia secession ordinance earlier in the year."[20]

The issue fractured the Unionist movement. Richard O. Curry divided the Unionists into four groups. "Thus, by the spring of 1862, Unionists of western Virginia had divided into four distinct factions: (1) opponents of statehood under any circumstances; (2) a militant free state group; (3) a moderate wing that feared the complications of the slavery question and attempted to avoid it; (4) a conservative faction that would oppose dismemberment rather than submit to Congressional interference."[21]

A convention to draft the new state constitution met in Wheeling on Nov. 26, 1861, with 61 members. The original name of the new state Kanawha was changed to "West Virginia". Delegates began to expand the boundaries of the new state to include more counties, at one time taking in all of the Shenandoah Valley, but the final tally was 48 counties, and the counties of Berkeley and Jefferson, provided they approved the constitution, which was done by a very small turnout of voters and which led to the 1871 Supreme Court decision which permanently gave those counties to West Virginia.

On April 3, 1862 a public vote was held on the constitution for the new state with 51 counties listed in the returns, with only Frederick county not included in the new state. The results were nearly identical to the vote on the statehood ordinance; 18,862 in favor and 514 against, with 13 counties giving no vote at all. [22]

Unionists who had been prominent supporters of the Wheeling government in 1861 found themselves on the outside by 1862. John Jay Jackson retired to his plantation in Wood County, Sherrard Clemens spoke against dismemberment throughout 1862, and even John Carlile, one of the primary proponents of statehood and one of Wheeling's "Virginia" senators in Washington, D.C., used his influence to derail the statehood bill. Wheeling's other senator, Waitman T. Willey, was able to restore the bill and attach an amendment to it authorizing gradual emancipation of slaves in the new state. Lincoln signed the statehood bill on Dec. 31, 1862.

On Jan. 1, 1863 Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation which freed slaves in territory in rebellion against the United States. The proclamation specifically exempted the 48 counties which at that time constituted West Virginia, since as a newly constituted Union state West Virginia was technically not "in rebellion", though in fact much of West Virginia was in rebellion, particularly those counties that had voted for the secession ordinance.[23]. Arthur Boreman wrote to Gov. Pierpont on Feb. 27, 1863, stating "After you get a short distance below the Panhandle, it is not safe for a loyal man to go into the interior out of sight of the Ohio River."[24]

West Virginia's constitutional emancipation amendment, known as the Willey Amendment, was put to a public vote on April 4, 1863. If passed, the new state was to take effect on June 20, 1863, which it did. The Willey amendment freed no slaves during the war and provided no emancipation for any slave over the age of 21. Slavery was ended in West Virginia by the legislature on Feb. 3, 1865.

May 28, 1863 was the election date for new state offices. Arthur Boreman was elected the first governor of the new state. Elections were also held for Virginia state offices under the Confederacy and West Virginians in at least nine counties voted in those elections, though returns are incomplete.[25][26] With the creation of West Virginia on June 20, 1863, Pierpont and the Restored Government of Virginia removed themselves to Alexandria, which was in Union control and later established themselves in Richmond at the war's end in 1865.

West Virginia civilians were arrested by both Confederate and Union authorities. Historian Mark E. Neely, Jr., found 337 cases of civilian arrest by the Confederacy in western Virginia, although this includes present-day southwestern Virginia as well as West Virginia.[27] Hundreds of civilians were also arrested by Union authorities, although the total number has not yet been determined.[28] Most were held in the Union prison Camp Chase in Cleveland, Ohio, though some were also held at Fort Delaware.

In 1865 the Wheeling government passed a law depriving the right to vote for anyone who had served in the Confederate armed forces or government, or who had been a sympathizer.[29] The state governments elected in 1863 and after were not fully representative of the population and were elected with a low turnout of voters. In 1864 Gov. Boreman was elected unopposed with 19,353 votes which representd 24% of the voting population. The state government in 1865 had a high percentage of non-native officers, including Gov. Boreman and 40% of the state legislature, who were natives of New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and other states.Many former Confederates left the state, such as Brig. Generals William L. Jackson of Wood County and John Echols of Monroe county. Guerrilla bands still operated in some counties and violent disturbances around the state required the presence of Federal troops, which remained until early 1869.[30][31]

Military Events[edit]

Although Virginia had a long western border with Ohio and Ohio's Governor Dennison had been organizing and arming regiments of soldiers the Richmond government made little attempt to defend its western counties. Robert E. Lee as commander of Virginia forces had ordered Alonzo Loring in Wheeling and F.M. Boykin to gather volunteers in the northern counties, and Col. Thomas J. Jackson to collect volunteers at Harper's Ferry. Gov. Letcher ordered the militia to muster, but many companies in the northern counties refused to do so. Militia in the central and southern counties responded but arms and supplies were lacking. Col. George A. Porterfield of Berkeley county was given command of forces in the northwest but conditions were chaotic. He eventually gathered about 1200 men, some of whom had to provide their own arms. Fearing that the gathering Ohio troops would use the railroad as an invasion route Porterfield ordered the burning of several railroad bridges. The commander of Union forces in Ohio, George McClellan, saw this as a reason to enter Virginia and sent two regiments across the Ohio river on May 26 into Wheeling and another two regiments into Parkersburg, south of Wheeling on the river.

Some Union volunteers had organized in Wheeling and the northern panhandle of Virginia and they managed to secure 2000 rifles from the Federal government. The 1st Virginia Infantry (Union) had been organized in Wheeling, though it consisted largely of Ohio and Pennsylvania men, its commander was Benjamin F. Kelley. The 1st Virginia along with McClellan's forces proceeded towards Col. Porterfield's command, which had moved to Philippi in Barbour County. On the morning of June 3, they were surprised by the Union troops and routed in what became known as the "Philippi races". Porterfield was relieved of his command and was replaced by Brig. Gen. Robert Garnett.

McClellan had delayed the invasion of the Kanawha river valley, having been informed by George W. Summers that his troops would be treated as invaders by the populace. On June 9 McClellan ordered Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox to cross the Ohio river with three Ohio regiments and two regiments officially designated "Kentucky", though they were mostly Ohio men also. Union troops suffered a minor defeat at Scary Creek, but soon captured Charleston on July 25.

Complicating the Confederate defense of the Kanawha valley was the appointment of former Virginia Governor John B. Floyd as a Brigadier-General assigned to the area and the senior officer to Brig. Gen. Henry A. Wise. Both men were political generals, without military training, and they had an intense antagonism towards each other. The inability to arm and supply their men was another severe handicap. Jedediah Hotchkiss stated "Nothing more fully illustrates the poverty of preparation that Virginia had made for a most gigantic warfare than General Floyd's appeal of July 1st, by special messenger, to the governors of South Carolina and Georgia, for the loan of arms."(pg. 60) After the Union defeat at 1st Manassas Henry Wise was pleading for a share of the small arms seized.

The weapons available to most West Virginians were the usual assortment of guns used in hunting and many were outdated. Rutherford B. Hayes commented in his diary at Weston, Taylor County, Aug. 12, 1861- "Wagon and cattle trains and small parties are fired on by guerrillas from the hills on two of the roads leading from here. Dr. Joe has about eight or ten in charge who have been wounded in this way. Two only have been killed. None in our regiment. The men all laugh at "squirrel guns" and the wounds they make. Several would have been killed if shot in the same part by the conical balls of our military guns." (pg. 63, Vol. 2)

On June 8th Brig. Gen. Robert S. Garnett assumed command of Confederate troops in northwestern Virginia.(Rice, pg. 125) Garnett arrived at Huttonsville, where Porterfield had assembled 24 companies, mostly from west Virginia. These were organized into the 25th Virginia Cavalry, the 31st Virginia Infantry, and the 9th Virginia Infantry Batallion. These troops were reinforced by Col. John Pegram commanding the 20th Virginia Infantry and other regiments from eastern Virginia and Georgia.(CMH17)

Garnett disposed 3,381 of his troops at Laurel Hill under his command, 1,300 at Rich Mountain under Col. Pegram, and 375 in the town of Beverly. He anticipated an attack by McClellan at his position at Laurel Hill, but McClellan instead sent Rosencrans on July 11th to attack Pegram at Rich Mountain. The battle resulted in a Union Victory and Garnett abandoned his position at Laurel Hill. (CMH 19) In his retreat he was pursued by Morris and in a battle at Corrick's Ford Gen. Garnett was killed, either by Union fire or friendly fire.(Fout DDCW)

Brig-Gen. Jacob D. Cox was given command of the 21st Ohio Regiment, the 11th Ohio, 12th Ohio, the 1st and 2nd Kentucky Regiments and ordered to Gallipolis, OH, and crossed the Ohio River on June 10th to Point Pleasant, VA. with a combined force of approximately 3,000 men.(JDCox, Milit Remin., pgs. 59-63) Former Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise, appointed a Brigadier-General, was raising Confederate troops in the Kanawha Valley and reported on July 8 a total force of 2,705. (OR, Series 1 Vol. 5 pg. 293). He would eventually assemble around 4,000. Military action in the Kanawha Valley was delayed by McClellan, who had been told by George W. Summers that most of the people in that region would regard the entry of Union forces as an invasion and unite in resistance.(Rice, pg. 127)

Cox began advancing his troops on July 11, moving up the Kanwaha River on flatboats. He ordered the 12th Ohio and 2 companies of the 21st Ohio towards Scary Creek, and there they engaged in a battle with Confederate forces under Capt. George S. Patton, who was wounded in the fighting. AG Jenkins rallied the troops and won the first victory for the Confederates in western Virginia. (Phillips, Soldier's Story, pgs 23-4) Nevertheless, Brig-Gen Wise retreated from Charleston to Lewisburg, although he had numerical superiority in troops.(White, og. 27)

Gen. Floyd surpised Federal troops at Cross Lanes on Aug. 26, which resulted in another Confederate victory. Floyd took up a position at Carnifex Ferry, and Rosencrans moved to attack Floyd from the north with 8 regiments. Floyd asked Wise for reinforcements but none were sent. The Federals attacked on Sept. 10th but were repulsed in 5 separate assaults. After nightfall Floyd managed to move his guns and troops across the river undetected into a stronger position. He estimated Confederate forces at 4,200 and Federal at 12,000. Floyd soon moved to join Brig.=Gen. Wise near Dogwood Gap and as Cox advanced the Confederates moved again to a position on Sewell Mountain.(White, pgs. 36-9)

Nov. 10 Guyandotte burned

Dec. 13 Battle Allegheny

Dec. 29-30 Sutton

1862

Stonewall Jackson was placed in charge of the district composing the Shenandoah, while Union commander Johnn C. Fremont was placed in charge of the newly created "Mountain Department", which included sections of western Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky. The B&O railroad was a primary concern to both Fremont and Jackson who, respectively, were committed to its protection and its destruction. Neither commander was completely successful in his goals. Fremont resigned his command in June of 1862 rather than serve under Major General John Pope.

Union forces under Jacob D. Cox sought to destroy the Virginia & Tennessee railroad but their efforts were unsuccessful, despite Union success in a battle at Lewisburg. No further attempts to destroy the railroad were made by Cox during the year.

After the Second Battle of Manassas, Henry Halleck ordered almost all Union troops from the Kanawha valley to protect Washington, D.C., leaving only 5,000 men under the command of Joseph Lightburn. Taking advantage of the situation, Confederate forces under the command of William W. Loring moved into the valley and drove Lightburn and his men from Virginia and across the Ohio river. Loring had little reinforcement however and facing a large advancing Union force he abandoned Charleston depsite orders to hold, and he was replaced by Lee with John Echols. This would be the last time Confederate forces would hold Charleston.

May 23 Battle Leisburg

Aug 22 Jenkins raid

Sept 11 Loring in Charleston

Oct 16 Exhols relieves Loring

Nov. 9 activities of Imboden

1863

On Jan. 20th Gen. Lee ordered Gen. Imboden to disrupt the efforts of the Pierpont government, to arrest any officials he could and to make the office of "sheriff" as dangerous as possible. On March 2 Imboden wrote to Lee outlining a plan for a large raid into western Virginia, an operation originally proposed by Hanse McNeill of Hardy county and enlarged by Imboden. The raid commenced on April 20 when Imboden left Shenanodah Mountain with 3,400 men of which 700 were cavalry. Coordinating with Imboden was Gen. William E> Jones, who left Rockingham county with about 2500 cavalry. Jones burned bridges along the B&O railroad line though failed in the attempt to burn the Cheat River bridge.

Imboden and Jones joined forces at Weston, Lewis county, where they were greeted by many in the town who were southern sympathizers. A flag had been made and presented to Gen. Jones. From Weston Jones proceeded to the oil field in Tyler county and burned the equipment and 150,000 barrels of crude oil. Before Union forces could counter the raid effectively Jones and Imboden returned to their home bases. They claimed to have destroyed 21 railroad bridges, commandered 5,000 head of cattle and 2,000 horses. Imboden recruited about 500 men and though Jones was also recruiting he did not report the number.

The actions of Gen. Jones, who treated all citizens, Union or Confederate, without sympathy, hurt Confederate efforts in western Virginia. Imboden, most of whose command were soldiers from West Virginia, was more careful in his accessing of horses and cattle. In Weston the citizens who had greeted the Confederate forces were punished by Gen. Roberts, about 60 of whom were sent to Camp Chase, and families were forced from their homes to be sent behind Confederate lines.

On May 23 William Averell was given command of Federal troops in West Virginia after Gen. Benjamin J. Roberts' poor performance in countering the raid. In June Imboden moved through Hampshire county on his way north preliminary to the Gettysburg campaign. The battle of Gettysburg from July 2-4 involved 4 West Virginia Union units; Battery C, Ist WV Light Artillery, 7th WV Infantry, 3rd WV Cavalry, and the 1st WV Infantry, though many of the soldiers were from Ohio and Pennsylvania. The greatest number of West Virginians in the battle however were in the Army of Northern Virginia, notably the Stonewall Brigade and Jenkin's Cavalry Brigade.

August 22 saw the Battle of White Sulphur Sprints in Greenbrier county between Averell and Confederate general Sam Jones and the course of the battle lasted 2 days.

1864

Feb 3 Scammon captured on boat

March 3 Breckenrige assumes command

May 2 Dublin raid

1865

Notes[edit]

- ^ Rice, Otis K. and Stephen W. Brown, West Virginia, A History, Second Edition, Univ. Press of Kentucky, 1993, pg. 114

- ^ Curry, Richard Orr, A House Divided, A Study of Statehood Politics and the Copperhead Movement in West Virginia, Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1965, pgs.141-147

- ^ How Virginia Convention Delegates Voted on Secession

- ^ Ambler, Charles Henry, A History of West Virginia, Prentice-Hall, 1933, pg. 318

- ^ Leonard, Cynthia Miller, The General Assembly of Virginia, July 30, 1619 - January 11, 1978, A Bicentennial Register of Members, Virginia State Library, 1978, pgs. 478-482

- ^ The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Series 1, Vol. 5, pg. 564

- ^ Ambler, Charles H., Francis H. Pierpont; Union War Governor of Virginia and Father of West Virginia, Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1937, pg. 188

- ^ Ambler, Charles Henry, A History of West Virginia, Prentice-Hall, 1933, pg. 357

- ^ Fones-Wolf, Ken, Reconstructing Appalachia, The Civil War's Aftermath, Univ. Press of Kentucky, 2010, pg. 239

- ^ Newell, Clayton R., Lee vs. McClellan, The First Campaign, Regnery Publishing, 1996, pg. 71

- ^ Geiger, Joe, Jr., Civil War in Cabell County, West Virginia 1861-1865, Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1991, pg. 13

- ^ Eldridge, Carrie, Torn Apart, How Cabell Countians Fought the Civil War, Heritage Books, 2007, intro.

- ^ Dickinson, Jack L., Wayne County, West Virginia in the Civil War, Hugginson Book Co., 2003, pg. 164

- ^ Putnam County, eWV, The West Virginia Encyclopedia [1]

- ^ Francis H. Peirpoint to Abraham Lincoln, Friday, August 01, 1862 (Recruitment in Virginia) [2]

- ^ Rafuse, Ethan, McClellan's War, The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union, Indiana Univ. Press, 2005, pg. 104

- ^ Snell, Mark, West Virginia and the Civil War, History Press, 2011, pgs. 28-29

- ^ Wallace, Lee A., Jr., A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations, 1861-1865, Virginia Civil War Commission, 1964, pgs. 261-299

- ^ How West Virginia Was Made, by Virgil A. Lewis, 1909, pgs. 262-263

- ^ Rice, Otis K. and Stephen W. Brown, pg. 140

- ^ Curry, pgs. 96-97

- ^ A Certified Copy of the Constitution of the State of West Virginia

- ^ Nicolay, John G. and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume VI, p. 419-420

- ^ Ambler, Charles H., Francis H. Pierpont: Union War Governor of Virginia and Father of West Virginia, Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1937, pg. 188

- ^ Martis, Kenneth C., The Historical Atlas of the Congresses of the Confederate States of America: 1861-1865, Simon & Schuster, 1994

- ^ Dubin, Michael J., United States Gubernatorial Elections, 1861-1911: The Official Results by State and Count, McFarland and Co., 2010. Pgs. 584-585

- ^ Neely, Mark E., Jr., Southern Rights, Political Prisoners and the Myth of Confederate Constitutionalism, Univ. Press of Virginia, 1999, pg. 120

- ^ The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1897, Series II, Vol. II, pgs. 264-266

- ^ Rice, pg. 156

- ^ Journal of the Senate of the State of West Virginia for the Sixth Session, Commencing January 21, 1868, Wheeling, WV, 1868, pgs. 8-10

- ^ Papers of Governor Arthur I. Boreman, Item 281 [3]