User:DeCausa/Maximilian I's cultural and scientific patronage

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death. Historians of the second half of the nineteenth century like Leopold von Ranke tended to criticize Maximilian for putting the interest of his dynasty above that of Germany, hampering the nation's unification process. Ever since Hermann Wiesflecker's Kaiser Maximilian I. Das Reich, Österreich und Europa an der Wende zur Neuzeit (1971-1986) became the standard work, a much more positive image of the emperor has emerged. He is seen as an essentially modern, innovative ruler who carried out important reforms and promoted significant cultural achievements, even if the financial price weighed hard on the Austrians and his military expansion caused the deaths and sufferings of tens of thousands of people.

Background and personal motivation[edit]

Maximilian I and his father Frederick III were part of what was to become a long line of Holy Roman Emperors from the House of Habsburg. Maximilian was elected King of the Romans in 1486; upon his father's death in 1493 he succeeded to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire.[1]

Maximilian was a keen supporter of the arts and sciences, and he surrounded himself with scholars such as Conrad Celtis Joachim Vadian and Andreas Stoberl (Stiborius), promoting them to important court posts. Many of them were commissioned to assist him complete a series of projects, in different art forms, intended to glorify for posterity his life and deeds and those of his Habsburg ancestors.[2][3] He referred to these projects as Gedechtnus ("memorial"),[3][4] which included a series of stylised autobiographical works: the epic poems Theuerdank and Freydal, and the chivalric novel Weisskunig, both published in editions lavishly illustrated with woodcuts.[2] In this vein, he commissioned a series of three monumental woodblock prints: The Triumphal Arch (1512–18, 192 woodcut panels, 295 cm wide and 357 cm high – approximately 9'8" by 11'8½"); and a Triumphal Procession (1516–18, 137 woodcut panels, 54 m long), which is led by a Large Triumphal Carriage (1522, 8 woodcut panels, 1½' high and 8' long), created by artists including Albrecht Dürer, Albrecht Altdorfer and Hans Burgkmair. According to The Last Knight: The Art, Armor, and Ambition of Maximilian I, Maximilian dictated large parts of the books to his secretary and friend Marx Treitzsaurwein who did the rewriting.[5] Authors of the book Emperor Maximilian I and the Age of Durer cast doubt on his role as a true patron of the arts though, as he tended to favor pragmatic elements over high arts.[6] On the other hand, he was a perfectionist who involved himself with every stage of the creative processes. His goals extended far beyond the emperor's own glorification too: commemoration also included the documentation in details of the presence and the restoration of source materials and precious artifacts.[7]

Notorious for his micro-managing, there was a notable case in which the emperor allowed and encouraged free-ranging, even wild improvisions: his Book of Prayers. The work shows a lack of constraint, and no consistent iconographic program on the part of the artist (Dürer), which would be realized and highly praised by Goethe in 1811.[8]

Literature[edit]

In 1504, Maximilian commissioned the Ambraser Heldenbuch, a compendium of German medieval narratives (the majority was heroic epics), which was written by Hans Ried. The work was of great importance to German literature because among its twenty five narratives, fifteen was unique.[9][10][11] This would be the last time the Nibelungenlied was enshrined in German literature before being rediscovered again 250 years later.[12][13] Maximilian was also a patron of Ulrich von Hutten whom he crowned as Poet Laureate in 1517 and the humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, who was one of Germany's most important patrons of arts in his own right.[14][15][16][17][18]

As Rex litteratus, he supported all the literary genres that had been supported by his predecessors, in addition to drama, a genre that had been gaining in popularity in his era. Joseph Grünpeck attracted his attention with Comoediae duae, presumably the first German Neo-Latin festival plays. He was impressed with Joseph Grünpeck's Streit zwischen Virtus und Fallacicaptrix, a morality play in which Maximilian himself was asked to choose between virtue and base pleasure.[19] Celtis wrote for him Ludus Dianae and Rhapsodia de laudibus et victoria Maximiliani de Boemannis. The Ludus Dianae displays the symbiotic relationship between ruler and humanist, who are both portrayed as Apollonian or Phoebeian, while Saturn – as counterpole of Phoebus – is a negative force and Bacchus as well as Venus display dangerous aspects in tempting humans towards a depraving life. Locher wrote the first German Neo-Latin tragedy, also the first German Humanist tragedy, the Historia de Rege Frantie. Other notable authors included Benedictus Chelidonius and Hieronymus Vehus. These plays often doubled as encomium or dramatized newe zeittung (news reports) in support of imperial or princely politics. [20][21][22] Douglas A.Russel remarks that the academic mode of theater associated with the new interest Humanism and the Classics at that time that was mainly the work of Konrad Celtis, Joachim von Watt (who was a poet laureate crowned by Maximilian and at age 32 was Rector at the University of Vienna), and Benedictus Chelidonius.[23][24] William Cecil MacDonald comments that, in the context of German medieval literary patronage, "Maximilian’s literary activities not only 'summarize' the literary patronage of the Middle Ages, but also represent a point of departure — a beacon for a new age." Moreover, "Like Charlemagne, Otto the Great, Henry II, and Frederick Barbarossa, Maximilian was a fostering spirit, i.e. he not only commissioned literature, but through his policies and the force of his personality he created a climate conducive to the flowering of the arts."[25][26]

Humanism[edit]

Universities[edit]

Under his rule, the University of Vienna reached its apogee as a centre of humanistic thought. He established the College of Poets and Mathematicians which was incorporated into the university.[29] Maximilian invited Conrad Celtis, the leading German scientist of their day to University of Vienna. Celtis found the Sodalitas litteraria Danubiana (which was also supported by Maximilian), an association of scholars from the Danube area, to support literature and humanist thought. Maximilian also promoted the development of the young Habsburg University of Freiburg and its host city, in consideration of the city's strategic position. He gave the city privileges, helped it to turn the corner financially while utilizing the university's professors for important diplomatic missions and key positions at the court. The Chancellor Konrad Stürtzel, twice the university's rector, acted as the bridge between Maximilian and Freiburg.[30][31][32][33] Maximilian supported and utilized the humanists partly for propaganda effect, partly for his genealogical projects, but he also employed several as secretaries and counsellors - in their selection he rejected class barriers, believing that "intelligent minds deriving their nobility from God", even if this caused conflicts (even physical attacks) with the nobles. He relied on his humanists to create a nationalistic imperial myth, in order to unify the Reich against the French in Italy, as pretext for a later Crusade (the Estates protested against investing their resources in Italy though).[34] Maximilian told his Electors each to establish a university in their realm. Thus in 1502 and 1506, together with the Elector of Saxony and the Elector of Brandenburg, respectively, he co-found the University of Wittenberg and the University of Frankfurt.[35] The University of Wittenberg was the first German university established without a Papal Bull, signifying the secular imperial authority concerning universities. This first center in the North where old Latin scholarly traditions were overthrown would become the home of Luther and Melanchthon.

Burgundian Netherlands[edit]

As he was too distant, his patronage of Humanism and humanistic books in particular did not reach the Netherlands (and as Mary of Burgundy died too young while Philip the Fair and Charles V were educated in the Burgundian tradition, there was no sovereign who fostered humanistic Latin culture in the Netherlands, although they had their own mode of learning.) [36] There were exchanges and arguments over political ideas and values between the two sides though. Maximilian greatly admired his father-in-law Charles the Bold (he even adopted Charles's motto as one of his own, namely, "I dared it!", or "Je l'ay emprint!") [37] and promoted his conception that the sovereign's power and magnificience came directly from God and not through the mediation of the Church. This concept was part of Maximilian's political program (including other elements such as the recovery of Italy, the position of the Emperor as dominus mundi, expansionism, the crusade...etc), supported in the Netherlands by Paul of Middelburg but considered extreme by Erasmus. Concerning heroic models that rulers should follow (especially concerning the education of Archiduke Charles, who would later be influenced much by his grandfather's knightly image), Antoine Haneron proposed ancient heroes, above all Alexander (who Charles also adopted as a great role model for all his life) while Molinet presented Alexander, Caesar and Semiramis, but Erasmus protested Alexander, Caesar and Xerxes as models. Maximilian strongly promoted the first two though, as well as St.George (both in "Frederican" and "Burgundian" forms). The idea of peace also became more pronounced in Maximilian's court in his last years though, likely influenced by Flemish humanism, especially Erasmian (Maximilian himself was an unabashed warlike prince, but late in his life, he did recognize that his 27 wars only served the devil[38]). Responding to the intense Burgundian humanistic discourse on nobility by birth and nobility by virtue, the emperor pushed his own modification: office versus birth (with a strong emphasis on the primacy of office over birth). Noflatscher opines that the emperor was probably the most important mediator of the Burgundian model himself, with Bianca Maria also having influence (although she could only partially fulfill her role).[39]

Philosophy and esotericism[edit]

In philosophy, besides Humanism, esotericism had a notable influence during Maximilian's time. In 1505, he sent Johannes Trithemius eight questions concerning spiritual and religious matters (Questions 3, 5, 6, 7 were concerned with witchcraft) that Trithemius answered and later published in the 1515 book Liber octo questionum (Books of eight questions). Maximilian displayed a skeptical aspect, posing questions such as why God permitted witches and their powers to control evil spirits.[40][41][42] The authors (now usually identified as Heinrich Kramer alone) of the most notorious work on witchcraft of the time, Malleus Maleficarum, claimed that they had his letter of approval (supposedly issued in November 1486) to act as inquisitors, but according to Behringer, Durrant and Bailey, he likely never supported them (although Kramer apparently went to Brussels, the Burgundian capital, in 1486, hoping to influence the young King – they did not dare to involve Frederick III, whom Kramer had offended some years earlier).[43][44] Trithemius dedicated the De septem secundeis ("The Seven Secondary Intelligences"), which argued that the cycle of ages was ruled by seven planetary angels, in addition to God (the First Intelligence).[45][46] The historian Martin Holleger notes though that Maximilian himself did not share the cyclical view of history, typical for their contemporaries, nor believed that their age would be the last age. He had a linear understanding of time – that progresses would make the world better.[47][a] The kabbalistic elements in the court as well as Trithemius himself influenced the thinking of the famous polymath and occultist Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (who in Maximilian's time served mainly as secretary, soldier and diplomatic spy).[49][50] The emperor, having interest in the occult himself, intended to write two books on magic (Zauberpuech) and black magic (Schwartzcunnstpuech) but did not have time for them.[51][52]

The Italian philosopher Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola dedicated his 1500 work De imaginatione, a treatise on the human mind (in which he synthesized Aristotle, Neoplatonism and Girolamo Savonarola), to Maximilian.[53][54] The Italian philosopher and theologian Tommaso Radini Tedeschi also dedicated his 1511 work La Calipsychia sive de pulchritudine animae to the emperor.[55][56]

Legal scholarship[edit]

The establishment of the new Courts and the formal Reception of Roman Law in 1495 led to the formation of a professional lawyer class as well as a bureaucratic judiciary. Legal scholars trained in mos italicus (either in Italian universities or in newly established German universities) became in demand.[57][58][59][60] Among the prominent lawyers and legal scholars who served Maximilian in various capacities and provided legal advices to the emperor were Mercurino Gattinara, Sebastian Brandt and Ulrich Zasius.[61][62] Together with the aristocrats and the literati (who participated in Maximilian's propaganda and intellectual projects), the lawyers and legal scholars became one of three main groups in Maximilian's court. Konrad Stürtzel, the Chancellor, belonged to this group. In Maximilian's court – more egalitarian than any previous German or Imperial court, with its burghers and peasants – all these groups were treated equally in promotions and rewards. The individuals were also blending in many respects, usually through marriage alliances.[63][64][65]

Library and encyclopaedic projects[edit]

Maximilian was an energetic patron of the library.[70] Previous Habsburg rulers such as Albert III and Maximilian's father Frederick III (who collected the 110 books that were the core inventory of the later library) had also been instrumental in centralizing art treasures and book collections.[71][72] Maximilian became a bibliophile during the time he was in the Low Countries.[73] As husband of Mary of Burgundy, he would come into possession of the huge Burgundian library, which according to some sources[74][75] was brought to Austria when he returned to his native land. According to the official website of the Austrian National Library though, the Habsburgs only brought the collection to Vienna in 1581.[68] Maximilian also inherited the Tyrol library of his uncle Sigismund, also a great cultural patron (which had received a large contribution from Eleanor of Scotland, Sigismund's wife and also a great lover of books).[76][77] When he married Bianca Maria, Italian masterpieces were incorporated into the collection.[68] The collection became more organized when Maximilian commissioned Ladislaus Sunthaim, Jakob Mennel and Johannes Cuspinian to acquire and compose books. By the beginning of the sixteenth century, the library had acquired significant Bohemian, French and Italian book art. In 1504, Conrad Celtis spoke the first time of the Bibliotheca Regia (which would evolve into the Imperial Library, and as it is named today, the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek or the Austrian National Library), an organized library that had been expanded through purchases.[74][78] Maximilian's collection was dispersed between Innsbruck, Vienna and Wiener Neustadt.[68] The Wiener Neustadt part was under Conrad Celtis's management. The more valuable part was in Innbruck.[79][80] Already in Maximilian's time, the idea and function of libraries were changing and it became important that scholars gained access to the books.[81][82] Under Maximilian, who was casual in his attitude to scholars (which marvelled the French chronicler Pierre Frossart[b], it was fairly easy for a scholar to gain access to the emperor, the court and thus the library.[84][85] But despite the intention of rulers like Maximilian II (and his chief Imperial Librarian Blotius) and Charles VI to make the library open to the general public, the process was only completed in 1860.[86][87]

During Maximilian's time, there were several projects of an encyclopaedic nature, among them the incomplete projects of Conrad Celtis. However, as the founder of the Collegium poetarum et mathematicorum and a "program thinker" (programmdenker, term used by Jan-Dirk Müller and Hans-Joachim Ziegeler), Celtis established an encyclopaedic-scientific model that increasingly integrated and favoured mechanical arts in relation to the combination between natural sciences and technology and associated them with divina fabrica (God's creation in the six days). In consistence with Celtis's design, the University's curriculum and the political and scientific order of Maximilian's time (which was also influenced by developments in the previous eras), the humanist Gregor Reisch, who was also Maximilian's confessor, produced the Margarita Philosophica, "the first modern encyclopaedia of any importance", first published in 1503. The work covers rhetoric, grammar, logic, music, mathematical topics, childbirth, astronomy, astrology, chemical topics (including alchemy), and hell.[88][89]

Cartography and ethnography[edit]

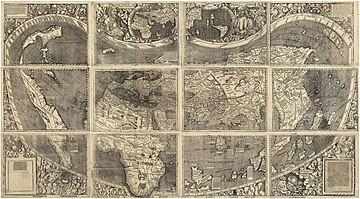

An area that saw many new developments under Maximilian was cartography, of which the important center in Germany was Nuremberg. In 1515 Dürer and Johannes Stabius created the first world map projected on a solid geometric sphere.[90][91] Bert De Munck and Antonella Romano make a connection between the mapmaking activities of Dürer and Stabius with efforts to grasp, manipulate and represent time and space, which was also associated with Maximilian's "unprecedented dynastic mythmaking" and pioneering printed works like the Triumphal Arch and the Triumphal Procession.[92] Maximilian assigned Johannes Cuspinianus and Stabius to compile a topography of Austrian lands and a set of regional maps. Stabius and his friend Georg Tannstetter worked together on the maps. The work appeared in 1533 but without maps. The 1528 Lazarus-Tannstetter map of Tabulae Hungariae (one of the first regional maps in Europe) though seemed to be related to the project. The cartographers Martin Waldseemüller and Matthias Ringmann dedicated their famous work Universalis Cosmographia to Maximilian, although the direct backer was Rene II of Loraine.[93] The 1513 edition of Geography, which contained this map and was also dedicated to Maximilian, by Jacobus Aeschler and Georgius Ubelin, is considered by Armando Cortes to be the climax of a cartography revolution.[94] The emperor himself dabbled in cartography.[95][c] According to Buisseret, Maximilian could "call upon a variety of cartographic talent unrivalled anywhere else in Europe at that time" (that included Celtis, Stabius, Cuspinianus, Jacob Ziegler, Johannes Aventinus and Tannstetter).[97] The development in cartography was tied to the emperor's special interest in sea route exploration, as an activity concerning his global monarchy concept, and his responsibilities as Duke consort to Mary of Burgundy, grandfather of the future ruler of Spain as well as ally and close relation to Portuguese kings. He sent men like Martin Behaim und Hieronymus Münzer to the Portuguese court to cooperate in their exploration efforts as well as to act as his own representatives.[98][99] Another involved in the network was the Flemish Josse van Huerter or Joss de Utra who would become the first settler of the island of Faial in the Portuguese Azores. Maximilian also played an essential role in connecting the financial houses in Augsburg and Nuremberg (including the companies of Höchstetter, Fugger and Welser etc) to Portuguese expeditions. In exchange for financial backing, King Manuel provided German investors with generous privileges. The humanist Conrad Peutinger was an important agent who acted as advisor to financiers, translator of voyage records and imperial councillor.[100] Harald Kleinschmidt opines that regarding the matter of world exploration as well as the "transformation of European world picture" in general, Maximilian was "a crucial though much underestimated figure" of his time.[101]

The evolution of cartography was connected to development in ethnography and the new Humanist science of chorography (promoted by Celtis at the University of Vienna).[102][103] As Maximilian already promoted the Ur-German after much archaeological and textual excavation as well as embraced the early German wildness, Peutinger correctly deduced that he would support German exploration of another primitive people as well. Using the Welser's commercial ventures as a pretext, Peutinger goaded Maximilian into backing his ethnographical interests in the Indians and supporting the 1505–1506 voyage of Balthasar Springer around Africa to India.[104][105] Besides, this endeavour added to the emperor's image as a conqueror and ruler, also to rival the claims of his arch-rival Suleiman the Magnificent regarding a global empire.[106] Based on an instruction dictated by Maximilian in 1512 regarding Indians in the Triumphal Procession, Jörg Kölderer executed a series of (now lost) drawings, which served as the guideline for Altdorfer's miniatures in 1513–1515, which in turn became the model for woodcuts (half of them based on now lost 1516–1518 drawings by Burgkmair) showing "the people of Calicut."[107] In 1518, Burgkmair produced the People of Africa and India series, focusing on depicting the peoples whom Springer encountered along coastal Africa and India.[104] The series brought into being "a basic set of analytic categories that ethnography would take as its methodological foundation".[108] As part of his dealings with Moscow, the Jagiellons and the Slavic East in general, Maximilian surrounded himself with people from the Slovenian territories and familiar with Slavic languages, such as Sigismund von Herberstein (himself a prominent ethnographer), Petrus Bonomo, Goerge Slatkonia and Paulus Oberstain. Political necessities overcame the prejudice against living languages, which started to find a place along Latin throughout central Europe, also in scholarly areas.[109][110]

Astrology, astronomy and horological instruments[edit]

The emperor's program of restoring the University of Vienna to its former pre-eminence was also concerned with astrology and astronomy. He realized the potential of the print press when combined with these branches of learning, and employed Georg Tannstetter (who, in 1509, was appointed by Maximilian as the Professor of Astronomy at the University of Vienna and also worked for a joint calendar reform attempt with the Pope) to produce yearly practica and wall calendars. In 1515, Stabius (who also acted as the court astronomer), Dürer and the astronomer Konrad Heinfogel produced the first planispheres of both southern and northerns hemispheres, also the first printed celestial maps. These maps prompted the revival of interest in the field of uranometry throughout Europe.[111][112][113][114] The Ensisheim meteorite fell on earth during the reign of Maximilian (7 November 1492). This was one of the oldest meteorite impacts in recorded history. King Maximilian, who was on his way to a campaign against France, ordered for it to be dug up and preserved at a local church. The meteorite, as a good omen, was utilized for propaganda against France through the use of broadsheets with dramatic pictures under the direction of the poet Sebastian Brandt (as Maximilian defeated a far larger French army to his own in Senlis two months later, the news would spread even more).[115][116][117] On the subject of calendars and calendar reform, already in 1484, the famous Flemish scientist Paul of Middelburg dedicated his Praenostica ad viginti annos duratura to Maximilian. His 1513 magnum opus Paulina de recta Paschae celebratione was also dedicated to Maximilian, together with Leo X.[118][119]

In addition to maps, other astrological, geometrical and horological instruments were also developed, chiefly by Stiborius and Stabius, who understood the need to cooperate with the emperors to make these instruments into useful tools for propaganda also.[120][121] The extraordinarily luxurious planetarium, that took twelve men to carry and was given as a diplomatic gift by Ferdinand I to Suleiman the Magnificient in 1541, originally belonged to Maximilian.[122][123] He loved to introduce newly invented musical instruments.[124][125] In 1506, he had a special regal, likely the apfelregal seen in one of Hans Weiditz's woodcuts, built for Paul Hofhaimer.[126][127] The emperor's favourite musical instrument maker was Hans Georg Neuschel, who created an improved trombone (Neuschel was a talented trombonist himself).[128][129] In 1500, an elaborated lathe (Drehbank) was created for the emperor's personal carpentry hobby. This is the earliest extant lathe, the earliest known surviving lapidary instrument as well as one of the earliest examples of scientific and technological furniture.[130] The earliest surviving screwdriver has also been found attached to one of his suits of armour.[131] Regiomontanus reportedly made an eagle automaton that moved and greeted him when he came to Nuremberg.[132] He liked to end his festivals with fireworks. In 1506, on the surface of Lake Konstanz, on the occasion of the gathering of the Reichstag, he staged a show of firework (this was the first recorded German firework, inspired by the example of Italian princes), completed with firework music provided by singers and court trumpeters. Machiavelli judged him as extravagant, but these were not fireworks done for pleasure, peaceful celebration or religious purpose as the type often seen in Italy, but a core ritual of Maximilian's court, that demonstrated the link between pyrotechnics and military technology. The show caused a stir (the news about the event was distributed through a Briefzeitung, or "letter newspaper"), leading to fireworks becoming fashionable. In the Baroque era, it would be a common form of self-stylization for monarchs.[133][134][135][136]

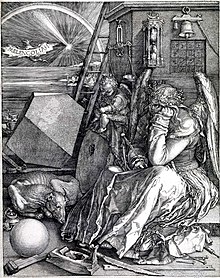

The development in astronomy, astrology, cosmography and cartography as well as an developing economy with demand for training in book-keeping is tied with the change in status and professionalization of mathematical studies (that once stood behind medicine, jurisprudence and theology as the lowest art) in the universities.[138] The leading figure was George Tanstetter (also the emperor's astrologer and physician), who provided his students with reasonably priced books through the collection and publication of works done by Joannes de Muris, Peuerbach and Regiomontanus and others, as well as wrote Viri Mathematici (Lives of Mathematicians), the first historical study of mathematics of Austria (and also a work to consolidate the position of astronomers, astrologers in Maximilian's court, in imitation of Maximilian's genealogical projects that reinforced his imperial titles).[139][140] The foremost exponent (and one of the founders[141][142]) of "descriptive geometry" was Albrecht Dürer himself, whose work Melencolia I was a prime representation[143][144] and inspired a lot of discussions, including its relation or non-relation to Maximilian's status as the most known melancholic of the time, his and his humanists' fear of the influence of the planet Saturn (some say that the engraving was a self-portrayal of Dürer while others think that it was a talisman for Maximilian to counter Saturn), the Triumphal Arch, hieroglyphics and other esoteric developments in his court, respectively etc. [145][146][147][148][149]

Medicine[edit]

Maximilian continued with the strong tradition of supporting physicians at court, started by his father Frederick III, despite Maximilian himself had little personal use for them (he usually consulted everyone's opinions and then opted for some self-curing folk practices).[150][151][152] He kept on his payroll about 23 court physicians, whom he "poached" during his long travels from the courts of his relatives, friends, rivals and urban hosts.[152] An innovative solution was entrusting these physicians with healthcare in the most important cities, for which purpose an allowance and horses were made available to them.[153] Alessandro Benedetti dedicated his Historia Corporis Humani: sive Anatomice (The Account of Human Body: or Anatomy) to the emperor.[154] As Humanism was established, the Medical Faculty of the University of Vienna increasingly abandoned Scholasticism and focused on studying laws of disease and anatomy based on actual experiences.[155] the early fifteenth century, the Medical Faculty of the University tried to gain influence upon the apothecaries of the city in order to enhance the dispensed medicines' quality and to enforce uniform preparation modes. Finally, in 1517, Maximilian granted them a privilege which allowed the faculty to inspect the Viennese pharmacies and to check the identity, quality and proper storage of the ingredients as well as the formulated preparations.[156] Likely a victim of syphilis (dubbed the "French disease" and used by Maximilian and his humanists like Joseph Grünpeck in their propaganda and artistic works against France) himself, Maximilian had an interest in the disease, which led him to establish eight hospitals in various hereditary lands.[157] He also retained an interest in the healing properties of berries and herbs all his life and invented a recipe for an invigorating stone beer.[158]

Archaeology[edit]

Maximilian had an interest in archaeology, "creative and participatory rather than objective and distancing" (and sometimes destructive), according to Christopher S.Wood.[161] His chief advisor on archaeological matters was Konrad Peutinger, who was also the founder of classical Germanic and Roman studies.[162] Peutinger commenced an ambitious project, the Vitae Imperatorum Augustorum, a series of biographies of emperors from Augustus to Maximilian (each biography would also include epigraphic and numismatic evidences), but only the early sections were completed. The search for medals ultimately led to a broad craze in Germany for medals as an alternative for portraiture. At the suggestion of the emperor, the scholar published his collection of Roman inscriptions.[163][164][165] Maximilian did not distinguish between the secular and the sacred, the Middle Ages and antiquity, and considered equal in archaeological value the various searches and excavations of the Holy Tunic (rediscovered in Trier in 1513 after Maximilian demanded to see it, and then exhibited, reportedly attracting 100,000 pilgrims), Roman and German reliefs and incriptions, etc. and the most famous quest of all, the search for the remains of hero Siegfried. Maximilian's private collection activities were carried out by his secretary, the humanist Johann Fuchsmagen, on his behalf. Sometimes, the emperor came in contact with antiquities during his campaigns – for example, an old German inscription found in Kufstein in 1504, that he immediately sent to Peutinger.[166][167][7][168] Around 1512–1514, Pirckheimer translated and presented Maximilian with Horapollo's Hieroglyphica. The hieroglyphics would be incorporated by Dürer into the Triumphal Arch, which Rudolf Wittkower considers "the greatest hieroglyphic monument".[169][170][171][172]

Cryptography[edit]

Maximilian's time was an era of international development for cryptography.[173] His premier expert on cryptography was the Abbot Trithemius, who dedicated Polygraphiae libri sex (controversially disguised as a treatise on occult, either because its real target audience was the selected few such as Maximilian or to attract public attention to a tedious field) to the emperor and wrote another work on steganography (Steganographia, posthumously published).[174][175][176]

Historiography and forged histories[edit]

In the fields of history and historiography, Trithemius was also a notable forger and inventive historian who helped to connect Maximilian to Trojan heroes, the Merovingians and the Carolingians.[179][180] The project had contributions from Maximilian's other court historiographers and genealogists such as Ladislaus Suntheim, Johann Stabius, Johannes Cuspinian and Jakob Mennel. While his colleagues like Jakob Mennel and Ladislaus Suntheim often inserted invented ancient ancestors for the missing links, Trithemius invented entire sources, such as Hunibald (supposedly a Scythian historian), Meginfrid and Wastald.[181][182][183][184] The historiographer Josef Grünpeck wrote the work Historia Friderici III et Maximiliani I (which would be dedicated to Charles V). The first history of Germany based on original sources (patronized by Maximilian and cultivated by Peutinger, Aventin, Pirchkheimer, Stabius, Cuspianian and Celtis) was the Epitome Rerum Germanicarum written by Jakob Wimpheling, in which it was argued that the Germans possessed their own flourishing culture.[185][186][187]

Maximilian's time was the age of great world chronicles.[188] The most famous and influential is the Nuremberg Chronicle, of which the author, Hartmann Schedel, is usually considered one of the important panegyrists and propagandists, hired and independent, of the emperor and his anti-Ottoman propaganda agenda.[189][190][191][192]

According to Maria Golubeva, Maximilian and his court preferred the fictional settings and reimagination of history (such as the Weisskunig, an "unique mixture of history and heroic romance"), so no outstanding works of historiography (such as those of Molinet and Chastelain at the Burgundian court) were produced.[193] The authors of The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 3: 1400-1800 point out three major distinctives in the historical literature within the imperial circle. The first was genealogical research, which Maximilian elevated to new heights and represented most prominently by the Fürstliche Chronik, written by Jakob Mennel. The second encompassed projects associated with the printing revolution, such as Maximilian's autobiographical projects and Dürer's Triumphal Arch. The third, and also the most sober strain of historical scholarship, constituted "a serious engagement with imperial legacy", with the scholar Johannes Cuspinianus being its most notable representative.[194] Seton-Watson remarks that all his important works show the connection to Maximilian, with the Commentarii de Romanorum Consulibus being "the most profound and critical"; the De Caesaribus et Imperatoribus Romanorum (also considered by Cesc Esteve as his greatest work[195]) possessing the most practical interest, especially regarding Maximilian's life, and the Austria giving a complete history of the nation up to 1519.[196]

Music[edit]

He had notable influence on the development of the musical tradition in Austria and Germany as well. Several historians credit Maximilian with playing the decisive role in making Vienna the music capital of Europe.[197][198][199] Under his reign, the Habsburg musical culture reached its first high point[200] and he had at his service the best musicians in Europe.[201] He began the Habsburg tradition of supporting large-scale choirs, which he staffed with the brilliant musicians of his days like Paul Hofhaimer, Heinrich Isaac and Ludwig Senfl.[202] His children inherited the parents' passion for music and even in their father's lifetime, supported excellent chapels in Brussels and Malines, with masters such as Alexander Agricola, Marbriano de Orto (who worked for Philip), Pierre de La Rue and Josquin Desprez (who worked for Margaret).[203] After witnessing the brilliant Burgundian court culture, he looked to the Burgundian court chapel to create his own imperial chapel. As he was always on the move, he brought the chapel as well as his whole peripatetic court with him. In 1498 though, he established the imperial chapel in Vienna, under the direction of Goerge Slatkonia, who would later become the Bishop of Vienna.[204] Music benefitted greatly through the cross-fertilization between several centres in Burgundy, Italy, Austria and Tyrol (where Maximilian inherited the chapel of his uncle Sigismund).[205]

In the service of Maximilian, Isaac (the first Continental composer who provided music on demand for the monarch-employer[206]) cultivated "the mass-proper genre with an intensity unrivalled anywhere else in Europe".[207] He created a huge cycle of polyphonic Mass Propers, most of which was published posthumously in the collection Choralis Constantinus, printed between 1550 and 1555 – David J. Rothenberg comments that, like many of the other artistic projects commissioned (and instilled with Maximilian's bold artistic vision and imperial ideology), it was never completed. A notable artistic monument, seemingly of great symbolic value to the emperor, was Isaac's motet Virgo prudentissima, which affiliated the reigns of two sovereign monarches – the Virgin Mary of Heaven and Maximilian of the Holy Roman Empire. The motet describes the Assumption of the Virgin, in which Mary, described as the most prudent Virgin (allusion to Parable of the Ten Virgins), “beautiful as the moon”, “excellent as the sun" and “glowing brightly as the dawn”, was crowned as Queen of Heaven and united with Christ, her bridegroom and son, at the highest place in Heaven. Rothenberg opines that Dürer’s Festival of the Rose Garlands (see below) was its "direct visual counterpart". The idea was also reflected in the scene of the Assumption seen in the Berlin Book of hours of Mary of Burgundy and Maximilian (commissioned when Mary of Burgundy was still alive, with some images added posthumously).[208][209]

The "Media Emperor"[edit]

Among some authors, Maximilian has a reputation as the "media emperor". The historian Larry Silver describes him as the first ruler who realized and exploited the propaganda potential of the print press both for images and texts.[210] The reproduction of the Triumphal Arch (mentioned above) in printed form is an example of art in service of propaganda, made available for the public by the economical method of printing (Maximilian did not have money to actually construct it). At least 700 copies were created in the first edition and hung in ducal palaces and town halls through the Reich.[211]

Historian Joachim Whaley comments that: "By comparison with the extraordinary range of activities documented by Silver, and the persistence and intensity with which they were pursued, even Louis XIV appears a rather relaxed amateur." Whaley notes, though, that Maximilian had an immediate stimulus for his "campaign of self-aggrandizement through public relation": the series of conflicts that involved Maximilian forced him to seek means to secure his position. Whaley further suggests that, despite the later religious divide, "patriotic motifs developed during Maximilian's reign, both by Maximilian himself and by the humanist writers who responded to him, formed the core of a national political culture."[212]

Historian Manfred Hollegger notes though that the emperor's contemporaries certainly did not see Maximilian as a "media emperor": "He achieved little political impact with pamphlets, leaflets and printed speeches. Nevertheless, it is certainly true that he combined brilliantly all the media available at that time for his major literary and artistic projects".[213] Tupu Ylä-Anttila notes that while his daughter (to whom Maximilian entrusted a lot of his diplomacy) often maintained a sober tone and kept a competent staff of advisors who helped her with her letters, her father did not demonstrate such an effort and occasionally sent emotional and erratic letters (the letters of Maximilian and Margaret were often presented to foreign diplomats to prove their trust in each other).[214] Maria Golubeva opines that with Maximilian, one should use the term "propaganda" in the sense suggested by Karl Vocelka: "opinion-making".[215] Also, according to Golubeva, unlike the narrative usually presented by Austrian historians including Wiesflecker, Maximilian's "propaganda", that was associated with 'militarism', universal imperial claims and court historiography, with a tendency towards world domination, was not the simple result of his Burgundian experience – his 'model of political competition' (as shown in his semi-autobiographical works), while equally secular, ignored the negotiable and institutional aspects inherent in the Burgundian model and, at the same time, emphasized top-down decision making and military force.[216]

During Maximilian's reign, with encouragement from the emperor and his humanists, iconic spiritual figures were reintroduced or became notable. The humanists rediscovered the work Germania, written by Tacitus. According to Peter H. Wilson, the female figure of Germania was reinvented by the emperor as the virtuous pacific Mother of Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.[217] Inheriting the work of Klosterneuburg canons and his father Frederick III, he promoted Leopold III, Margrave of Austria (who had family ties to the emperor), who was canonized in 1485 and became the Patron of Austria in 1506.[218][219][220] To maximize the effect that consolidated his rule, the emperor delayed the translation of Leopold's bones for years until he could personally be there.[221][222]

He promoted the association between his own wife Mary of Burgundy and the Virgin Mary, that had already been started in her lifetime by members of the Burgundian court before his arrival. These activities included the patronage (by Maximilian, Philip the Fair and Charles V) of the devotion of the Seven Sorrows[226][227][228][229] as well as the commission (by Maximilian and his close associates) of various artworks dedicating to the topic such as the famous paintings Feast of the Rosary (1506) and Death of the Virgin (1518, one year before the emperor's death) by Albrecht Dürer,[230][231] the famous diptych of Maximilian's extended family (after 1515) by Strigel,[232] the Manuscript VatS 160 by the composer Pierre Alamire.[233]

The German language[edit]

Maximilian's reign witnessed the gradual emergence of the German common language. His chancery played a notable role in developing new linguistic standards. Martin Luther credited Maximilian and the Wettin Elector Frederick the Wise with the unification of German language. Tennant and Johnson opine that while other chanceries have been considered significant and then receded in important when the research direction changes, the chanceries of these two rulers have always been considered important from the beginning. As a part of his influential literary and propaganda projects, Maximilian had his autobiographical works embellished, reworked and sometimes ghostwritten in the chancery itself. He is also credited with a major reform of the imperial chancery office: "Maximilian is said to have caused a standardization and streamlining in the language of his Chancery, which set the pace for chanceries and printers throughout the Empire."[234] The form of written German language he introduced into his chancery was called Maximilian's Chancery Speech (Maximilianische Kanzleisprache) and considered a form of Early New High German. It replaced older forms of written language that were close to Middle High German. This new form was used by the imperial chanceries until the end of the 17th century and therefore also referred to as the Imperial speech.[235]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "His belief in progress was already remarkably “modern,” leading him to instruct obstinate powers like the Austrian estates that the world was constantly moving forward into a better future, so that they should just allow him to set his reforms in motion even if they failed to understand the new developments themselves."[48]

- ^ "'The Emperor', he writes, 'not only calls them his friends, but treats them as such, and it appears to me that he seeks their society gladly, and is much influenced by them. There is certainly no other ruler who is so willing to learn from those more learned than he is, and whose own mind is so cultivated that his questions are themselves instructive'.")[83]

- ^ [...]The bishop of Chiemsee, writing to the cardinal of Siena in January of 1491, that Maximilian knew the topography of his lands so well that he could jot down an impromptu map of any region."[96]

- ^ "Maximilian and his father Emperor Frederick III were present at the 1475 gathering in Cologne, and were among the first members of the Fraternity of the Rosary. Barely three years later, in 1478, the Burgundian court chronicler Molinet added his allegoric eulogy Le chappellet des dames, in which he placed a symbolic rosary (chappellet) upon the head of Maximilian’s first wife Mary. It is in this same allegory that the birth of Philip receives its parallel in the depiction of the baby Jesus in a manger, surrounded by an ox and an ass. The German-speaking community in Venice also united in a Fraternity of the Rosary. It was for this fraternity in 1506 that Dürer began his famous Feast of the Rosary in Augsburg. This painting is extraordinary because of the extreme tenderness with which the Virgin Mary, now in her function as Virgin with Child Enthroned, places a rosary of white and red roses upon the head of Maximilian. In so doing, Dürer made a single entity of the religious and the worldly".[224]

References[edit]

- ^ Terjanian 2019, p. 303

- ^ a b Watanabe-O'Kelly, Helen (2000). The Cambridge History of German Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-521-78573-0. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ a b Westphal, Sarah (2012). "Kunigunde of Bavaria and the 'Conquest of Regensburg': Politics, Gender and the Public Sphere in 1485". In Emden, Christian J.; Midgley, David (eds.). Changing Perceptions of the Public Sphere. Berghahn Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-85745-500-0. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ Kleinschmidt 2008, p. 162.

- ^ Terjanian 2019, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Michel & Sternat 2012, p. 16.

- ^ a b Terjanian 2019, p. 56.

- ^ Bulletin. Department of Fine Arts of Oberlin College. 1997. p. 9. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ Konzett, Matthias (11 May 2015). Encyclopedia of German Literature. Routledge. p. 449. ISBN 978-1-135-94129-1. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Classen, Albrecht (30 June 2011). Sexual Violence and Rape in the Middle Ages: A Critical Discourse in Premodern German and European Literature. Walter de Gruyter. p. 63. ISBN 978-3-11-026338-1. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Gentry, Francis G.; Wunderlich, Werner; McConnell, Winder; Mueller, Ulrich (2002). The Nibelungen Tradition: An Encyclopedia. Psychology Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8153-1785-2. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Wagner, Richard (2010). Wagner's Ring in 1848: New Translations of The Nibelung Myth and Siegfried's Death. Camden House. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-57113-379-3. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Nissen, Cristina (April 2013). Das Nibelungenlied als Volksbuch: Friedrich Heinrich von der Hagen und der moderne Mythos des ?Nibelungenliedes? (in German). Diplomica Verlag. p. 54. ISBN 978-3-8428-9483-9. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Walker, Richard Ernest (2008). Ulrich Von Hutten's Arminius. Peter Lang. p. 83. ISBN 978-3-03911-338-5. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Konzett 2015, p. 449.

- ^ Posset, Franz (23 April 2021). Catholic Advocate of the Evangelical Truth: Marcus Marulus (Marko Marulić) of Split (1450-1524): Collected Works, Volume 5. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-5326-7870-7. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Fletcher, Stella (4 February 2014). The Longman Companion to Renaissance Europe, 1390-1530. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-317-88562-7. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Müller & Ziegeler 2015, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Silver 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Orbán, Áron (2017). "Born for Phoebus: solar-astral symbolism and poetical self-representation in Conrad Celtis and his humanist circles": 40, 57, 134, 183–186, 193–196. doi:10.14754/CEU.2017.01.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|access-date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|access-date= - ^ Bloemendal, Jan; Norland, Howard (19 September 2013). Neo-Latin Drama in Early Modern Europe. BRILL. pp. 112–117, 136, 141, 145, 178. ISBN 978-90-04-25746-7. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ Dietl, Cora (8 February 2021). "Staging reformation as history-Three exemplary cases: Agricola, Hartmann, Kielmann". In Happé, Peter; Hüsken, Wim (eds.). Staging History: Essays in Late Medieval and Humanist Drama. BRILL. p. 193. ISBN 978-90-04-44950-3. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ Russell, Douglas A. (31 December 1981). An Anthology of Austrian Drama. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8386-2003-8. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ Gordon, F. Bruce (30 November 2021). Zwingli: God's Armed Prophet. Yale University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-300-25879-0. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ McDonald & Goebel 1973, p. 186.

- ^ MacDonald, William Cecil (1974). A survey of German medieval literary patronage from Charlemagne to Maximilian I. p. 215222.

- ^ Kastenholz, Richard (2006). Hans Schwarz: ein Augsburger Bildhauer und Medailleur der Renaissance (in German). Deutscher Kunstverlag. p. 147. ISBN 978-3-422-06526-0. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Schauerte, Thomas (2012). "Model Germania". Europäische Geschichte Online. Institut für Europäische Geschichte. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Janin, Hunt (2014). The University in Medieval Life, 1179-1499. McFarland. p. 13. ISBN 9780786452019. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ European Medieval Drama Council, Société internationale pour l'étude du théâtre médiéval (2002). European Medieval Drama: Papers from the ... International Conference on European Medieval Drama. Brepols. p. 111. ISBN 978-2-503-51397-3. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Scott, Tom (23 March 2016). The Early Reformation in Germany: Between Secular Impact and Radical Vision. Routledge. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-317-03486-5. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ The Cambridge Modern History. Macmillan Company. 1912. p. 325. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Bietenholz & Deutscher 2003, p. 470.

- ^ Michel & Sternat 2012, pp. 31, 32, 34.

- ^ Rashdall, Hastings (1958). The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages: Italy, Spain, France, Germany, Scotland, etc. Oxford University Press. p. 268. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Wijsman, Hanno (24 September 2010). "'Northern renaissance? Burgundy and Netherlandish art in Fifteenth-Century Europe". In Lee, Alex; Péporté, Pierre; Schnitker, Harry (eds.). Renaissance? Perceptions of Continuity and Discontinuity in Europe, c.1300- c.1550. BRILL. pp. 284, 287. ISBN 978-90-04-18841-9.

- ^ Brady 2009, p. 108.

- ^ Holleger 2012, pp. 25, 26.

- ^ Noflatscher & 740–743.

- ^ Behringer, Wolfgang (13 November 2003). Witchcraft Persecutions in Bavaria: Popular Magic, Religious Zealotry and Reason of State in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-521-52510-7. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Silver 2008, p. 134.

- ^ Zambelli, Paola (30 July 2007). White Magic, Black Magic in the European Renaissance: From Ficino, Pico, Della Porta to Trithemius, Agrippa, Bruno. BRILL. p. 63. ISBN 978-90-474-2138-2. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Durrant, Jonathan Bryan; Bailey, Michael David (2012). Historical Dictionary of Witchcraft. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8108-7245-5. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Behringer, Wolfgang (2008). "Malleus Malificarum". In Golden, Richard M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Witchcraft: The Western Tradition. K - P. ABC-CLIO. pp. 717–723. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (14 October 2008). The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 52–54. ISBN 978-0-19-971756-9. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Brann 1999, p. 133.

- ^ McKechneay, Maya; ORF.at, für (12 January 2019). "Maximilian I.: Reformer bei Tag, Ritter bei Nacht". news.ORF.at (in German). Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Holleger 2012, p. 25.

- ^ Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von (1993). Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Llewellyn Worldwide. p. xvi–xix. ISBN 978-0-87542-832-1. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Place, Robert (17 March 2005). The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination. Penguin. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-4406-4975-2. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Silver 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Benecke 2019, p. ii.

- ^ Grassi, Ernesto (31 December 2000). Rhetoric as Philosophy: The Humanist Tradition. SIU Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8093-2363-0. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Zittoun, Tania; Glǎveanu, Vlad Petre (2018). Handbook of Imagination and Culture. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-19-046871-2. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Bietenholz, Peter G.; Deutscher, Thomas Brian (1 January 2003). Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and Reformation. University of Toronto Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8020-8577-1. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ "RADINI TEDESCHI, Tommaso in "Dizionario Biografico"". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Thornhill 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Burdick 2004, pp. 19, 20.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Theodore (31 May 2018). Clio the Romantic Muse: Historicizing the Faculties in Germany. Cornell University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-5017-1128-2. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Lee, Daniel (19 February 2016). Popular Sovereignty in Early Modern Constitutional Thought. Oxford University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-19-106244-5. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Kinney, Arthur F.; Swain, David W.; Hill, Eugene D.; Long, William A. (17 November 2000). Tudor England: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-136-74530-0. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Plessis, Paul J. du (14 December 2015). Reassessing Legal Humanism and its Claims: Petere Fontes?. Edinburgh University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-4744-0886-8. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Müller, Jan-Dirk (15 October 2003). "The court of Emperor Maximilian I". In Vanderjagt, A.J. (ed.). Princes and Princely Culture 1450-1650, Volume 1. BRILL. pp. 295–302. ISBN 978-90-04-25352-0. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Brady 2009, p. 113.

- ^ . p. 457 https://books.google.com/books?id=M4VUAAAAYAA. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Kren, Thomas; McKendrick, Scot (1 July 2003). Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe. Getty Publications. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-89236-704-7. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Evans, Mark (1992). The Sforza Hours. British Library. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7123-0268-5. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "1500: Emperor Maximilian I and the Origins of the "Bibliotheca Regia" - Österreichische Nationalbibliothek". www.onb.ac.at. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Trenkler, Ernst (1948). Das Schwarze Gebetbuch (in German). F. Deuticke. p. 19. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Brechka, Frank T. (6 December 2012). Gerard Van Swieten and His World 1700–1772. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 120. ISBN 978-94-010-3223-0. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "1440: Kaiser Friedrich III. und das böhmische Erbe - Österreichische Nationalbibliothek". www.onb.ac.at. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Stam, David H. (2001). International Dictionary of Library Histories. Taylor & Francis. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-57958-244-9. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Heyworth, Gregory; O'sullivan, Daniel E.; Coulson, Frank (25 July 2013). Les Eschéz d'Amours: A Critical Edition of the Poem and its Latin Glosses (in French). BRILL. p. 43. ISBN 978-90-04-25070-3. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ a b Stam 2001, p. 200.

- ^ Heyword, 2003 & 43.

- ^ Trevor-Roper, Hugh (23 January 1989). Renaissance Essays. University of Chicago Press. pp. 18, 19. ISBN 978-0-226-81227-4. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Benecke 2019, p. 78.

- ^ "Timeline - Österreichische Nationalbibliothek". www.onb.ac.at (in German). Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Drake, Miriam A. (2003). Ency of Library and Inform Sci 2e V4 (Print). CRC Press. p. 2499. ISBN 978-0-8247-2080-3. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Kent, Allen (28 February 1986). Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science: Volume 40 - Supplement 5: Austria: National Library of to The Swiss National Library. CRC Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8247-2040-7. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "1514: Gelehrte und ihre Bibliotheken - Österreichische Nationalbibliothek". www.onb.ac.at. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Nationalbibliothek, Österreichische (1975). Jahresbericht - Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (in German). Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. p. 1. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Janssen 1905, p. 160.

- ^ Janssen, Johannes (1905). History of the German People at the Close of the Middle Ages. Kegan Paul. p. 160. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Fathers, Paulist (29 March 2017). The Catholic World, Vol. 42: A Monthly Magazine of General Literature and Science; October, 1885, to March, 1886 (Classic Reprint). Fb&c Limited. p. 661. ISBN 978-0-243-33652-4. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Wiegand, Wayne A.; Davis, Donald G. Jr (28 January 2015). Encyclopedia of Library History. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-135-78750-9. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W. (7 September 2016). Canonical Texts and Scholarly Practices. Cambridge University Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-1-107-10598-0. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Müller & Ziegeler 2015, pp. 84–88.

- ^ Greenberg, Arthur (15 December 2006). From Alchemy to Chemistry in Picture and Story. John Wiley & Sons. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-470-08523-3. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Crane, Nicholas (16 December 2010). Mercator: The Man who Mapped the Planet. Orion. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-297-86539-1. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Bagrow, Leo (12 July 2017). History of Cartography. Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-351-51558-0. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Munck, Bert De; Romano, Antonella (20 August 2019). Knowledge and the Early Modern City: A History of Entanglements. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-429-80843-2. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Kleinschmidt, Harald (2000). Understanding the Middle Ages: The Transformation of Ideas and Attitudes in the Medieval World. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-770-2. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Cortesão, Armando (1969). History of Portuguese Cartography. Junta de Investigações do Ultramar. p. 124. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Buisseret, David (22 May 2003). The Mapmakers' Quest: Depicting New Worlds in Renaissance Europe. OUP Oxford. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-19-150090-9. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Buisseret 2003, p. 54.

- ^ Buisseret 2003, p. 55.

- ^ Kleinschmidt 2008, pp. 204–224.

- ^ Schrott, Lambert (1933). Pioneer German Catholics in the American Colonies (1734-1784). United States Catholic historical society. p. 112. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Schrott, Lambert (1933). Pioneer German Catholics in the American Colonies (1734-1784) (PDF). United States Catholic historical society. pp. 50, 60, 61, 70, 80, 110. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Kleinschmidt 2008, p. xii.

- ^ Poe, Marshall T. (1 January 2002). A People Born to Slavery": Russia in Early Modern European Ethnography, 1476–1748. Cornell University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8014-7470-5. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Lindberg, David C.; Porter, Roy; Numbers, Ronald L.; Press, Cambridge University; Park, Katharine; Daston, Lorraine; Daston, Professor Lorraine; Nye, Mary Jo; Ross, Dorothy; Porter, Theodore M. (2003). The Cambridge History of Science: Volume 3, Early Modern Science. Cambridge University Press. p. 488. ISBN 978-0-521-57244-6. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b Noflatscher 2011, p. 236.

- ^ Leitch, Stephanie (June 2009). "Burgkmair's Peoples of Africa and India (1508) and the Origins of Ethnography in Print" (PDF). The Art Bulletin. 91 (2): 134–159. doi:10.1080/00043079.2009.10786162. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Fichtner 2014, p. 78.

- ^ Feest, Christian (August 2014). "The people of Calicut: objects, texts, and images in the Age of Proto-Ethnography" (PDF). Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas. 9 (2): 295–296. doi:10.1590/1981-81222014000200003. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Leitch 2009, p. 135.

- ^ Luthar, Oto (2008). The Land Between: A History of Slovenia. Peter Lang. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-3-631-57011-1. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Poe 2002, pp. 118, 119.

- ^ Noflatscher 2011, p. 245.

- ^ Lachièze-Rey, Marc; Luminet, Jean-Pierre; France, Bibliothèque nationale de (16 July 2001). Celestial Treasury: From the Music of the Spheres to the Conquest of Space. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-521-80040-2. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (9 February 2018). Scandalous Error: Calendar Reform and Calendrical Astronomy in Medieval Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-19-252018-0. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Hayton 2015, p. 92.

- ^ Darin 2015, p. 51.

- ^ Reich, Aaron. "Meteor impacts Ensisheim 529 years ago in oldest recorded impact". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Golia, Maria (15 October 2015). Meteorite: Nature and Culture. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-547-9. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Soranzo, Matteo (22 April 2016). Poetry and Identity in Quattrocento Naples. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-317-07944-6. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (6 October 2011). Dating the Passion: The Life of Jesus and the Emergence of Scientific Chronology (200–1600). BRILL. pp. 226, 227. ISBN 978-90-04-21707-2. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Hayton, 2015 & 98–117.

- ^ Kremer, Richard L. (February 2016). "Playing with Geometrical Tools: Johannes Stabius's Astrolabium imperatorium (1515) and Its Successors: Geometrical tools". Centaurus. 58 (1–2): 104–134. doi:10.1111/1600-0498.12112. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Rogers, J. M.; Rogers, John Michael; Ward, R. M.; Museum, British (1988). Süleyman the Magnificent. British Museum Publications. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7141-1440-8. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ İnalcık, Halil; Kafadar, Cemal (1993). Süleymân the Second and His Time. Isis Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-975-428-052-4. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Boydell, Barra (1982). The Crumhorn and Other Renaissance Windcap Instruments: A Contribution to Renaissance Organology. F. Knuf. p. 25. ISBN 978-90-6027-424-8. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Cuyler 1973, p. 85.

- ^ Keyl, Stephen (1989). Arnolt Schlick and Instrumental Music Circa 1500. Duke University. p. 196. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Kini, Katja (2016). "Konzert "Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen" am 3. Februar". MeinBezirk.at (in German). Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Clemencic, René (1973). Old Musical Instruments. Octopus Books. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7064-0057-1. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Polk, Keith (2005). Tielman Susato and the Music of His Time: Print Culture, Compositional Technique and Instrumental Music in the Renaissance. Pendragon Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-57647-106-7. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Bedini, Silvio A. (1999). Patrons, Artisans, and Instruments of Science, 1600-1750. Ashgate/Variorum. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-86078-781-5. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Keller, Alex (1965). A Theatre of Machines. Macmillan. p. 93. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Riskin, Jessica (8 February 2018). The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument Over What Makes Living Things Tick. University of Chicago Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-0-226-52826-7. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Kelber, Moritz (2018). Die Musik bei den Augsburger Reichstagen im 16. Jahrhundert (in German). Allitera Verlag. p. 143. ISBN 978-3-96233-095-8. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Helm, Franz; Leng, Rainer (2001). Franz Helm und sein "Buch von den probierten Künsten": ein handschriftlich verbreitetes Büchsenmeisterbuch in der Zeit des frühen Buchdrucks (in German). Isd. p. 38. ISBN 978-3-89500-223-6. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Hanimann, Beda. "Faszination Feuerwerk". St.Galler Tagblatt (in German). Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Jung, Vera (2001). Körperlust und Disziplin: Studien zur Fest- und Tanzkultur im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert (in German). Böhlau. p. 214. ISBN 978-3-412-11600-2. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Warburg, Aby (1999). The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity: Contributions to the Cultural History of the European Renaissance. Getty Publications. p. 636. ISBN 978-0-89236-537-1. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Brüning, Jochen (16 June 2015). "Mathematik und Mathematiker im Umkreis. Maximilians". In Müller, Jan-Dirk; Ziegeler, Hans-Joachim (eds.). Maximilians Ruhmeswerk: Künste und Wissenschaften im Umkreis Kaiser Maximilians I. (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 185–207. ISBN 978-3-11-035102-6. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Dauben, Joseph W.; Scriba, Christoph J. (23 September 2002). Writing the History of Mathematics: Its Historical Development. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 215. ISBN 978-3-7643-6167-9. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Hayton 2015, p. 90.

- ^ Ryan, Daniel L. (18 December 1991). CAD/CAE Descriptive Geometry. CRC Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8493-4273-8. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Finkelstein, David (1 January 2017). The Melencolia Manifesto. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-68174-090-4. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Edson, Gary (18 September 2012). Mysticism and Alchemy through the Ages: The Quest for Transformation. McFarland. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-7864-9088-2. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Bubenik, Andrea (4 July 2019). The Persistence of Melancholia in Arts and Culture. Routledge. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-429-88776-5. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Klibansky, Raymond; Panofsky, Erwin; Saxl, Fritz (21 November 2019). Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 317, 327. ISBN 978-0-7735-5952-3. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Giehlow, Karl. Dürers Stich "Melencolia I" und der maximilianische Humanistenkreis (in German). Gesellsch. f. Vervielfält. Kunst.

- ^ Despoix, Philippe; Tomm, Jillian (21 November 2018). Raymond Klibansky and the Warburg Library Network: Intellectual Peregrinations from Hamburg to London and Montreal. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-7735-5607-2. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Merback, Mitchell B. (2 January 2018). Perfection's Therapy: An Essay on Albrecht Dürer's Melencolia I. Princeton University Press. pp. 39, 256, 356, 321, 322. ISBN 978-1-935408-75-8.

- ^ Dürer, Albrecht (1977). The Intaglio Prints of Albrecht Dürer: Engravings, Etchings & Drypoints. Kennedy Galleries. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-87920-001-5. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ MacDonald, Alasdair A.; Twomey, Michael W.; Twomey, Mw (2004). Schooling and Society: The Ordering and Reordering of Knowledge in the Western Middle Ages. Peeters Publishers. p. 121. ISBN 978-90-429-1410-0. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Siraisi, Nancy G. (26 February 2019). History, Medicine, and the Traditions of Renaissance Learning. University of Michigan Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-472-03746-9. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ a b Benecke 2019, p. 21.

- ^ Kostenzer, Otto (1970). "Die Leibärzte Kaiser Maximilians I. in Innsbruck" (PDF). Veröffentlichungen des Tiroler Landesmuseums Ferdinandeum. 50: 73. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Conrad, Lawrence I.; Neve, Michael; Nutton, Vivian; Porter, Roy; Wear, Andrew (17 August 1995). The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-521-47564-8. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Hare 1913, p. 289.

- ^ Kletter (editor), Christa; Working Group "History of Pharmacopoeias" of the International Society for the History of Pharmacy (2015). The Civil Pharmacopoeias of Austria (PDF). International Society for the History of Pharmacy - ISHP. p. 1. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ Savinetskaya, Irina (2016). The Politics and Poetics of Morbus Gallicus in the German Lands (1495 - 1520) (PDF). pp. 17, 24, 45. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Holleger 2005, p. 258.

- ^ Foster, Russell (26 June 2015). Mapping European Empire: Tabulae imperii Europaei. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-317-59306-5. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Wood & 2008 231.

- ^ Wood, Christopher S. (2005). "Maximilian I as Archeologist". Renaissance Quarterly 58. 58 (4): 1128–1174. doi:10.1353/ren.2008.0988. JSTOR 10.1353/ren.2008.0988. S2CID 194186440. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Dos Santos Lopes, Marília (11 May 2016). Writing New Worlds: The Cultural Dynamics of Curiosity in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4438-9430-2. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Jecmen, Gregory; Spira, Freyda (2012). Imperial Augsburg: Renaissance Prints and Drawings, 1475-1540. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-84822-122-2. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Scher, Stephen K. (21 August 2013). Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal: Portrait Medals of the Renaissance. Routledge. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-134-82194-5. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Silver 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Wood, Christopher S.; Wood, Professor Christopher S. (15 August 2008). Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art. University of Chicago Press. pp. 179, 225. ISBN 978-0-226-90597-6. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Jenkins, Simon (4 November 2021). Europe's 100 Best Cathedrals. Penguin Books Limited. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-241-98956-2. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ The journal of medieval and early modern studies. Duke University Press. 1998. p. 105. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Giehlow, Karl (27 January 2015). The Humanist Interpretation of Hieroglyphs in the Allegorical Studies of the Renaissance: With a Focus on the Triumphal Arch of Maximilian I. Hotei Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-90-04-28173-8. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Niliacus, Horapollo (30 June 2020). The Hieroglyphics of Horapollo. Princeton University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-691-21506-8. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Fritze, Ronald H. (4 February 2021). Egyptomania: A History of Fascination, Obsession and Fantasy. Reaktion Books. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-78023-685-8. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Smith, Jeffrey Chipps (15 December 2014). Nuremberg, a Renaissance City, 1500-1618. University of Texas Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4773-0638-3. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Hill, David Jayne (1906). A History of Diplomacy in the International Development of Europe. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 156. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Muchembled, Robert; Bethencourt, Francisco; Monter, William; Egmond, Florike (March 2007). Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-521-84548-9. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Brann, Noel L. (1 January 1999). Trithemius and Magical Theology: A Chapter in the Controversy over Occult Studies in Early Modern Europe. SUNY Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7914-3962-3. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Ellison, Katherine (10 June 2016). A Cultural History of Early Modern English Cryptography Manuals. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-315-45820-5. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Kahn, David (5 December 1996). The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. Simon and Schuster. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-4391-0355-5. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Strasser, Gerhard F. (26 September 2017). "Wolfenbüttel, a Minor German Duchy But a Major Center of Cryptology in the Early Modern Period". Tatra Mountains Mathematical Publications. 70 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1515/tmmp-2017-0018. S2CID 165190323. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Brann, Noël L. (1 January 1981). The Abbot Trithemius (1462-1516): The Renaissance of Monastic Humanism. BRILL. p. 95. ISBN 978-90-04-06468-3. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Grafton, Anthony; Grafton, Professor of History Anthony (2009). Worlds Made by Words: Scholarship and Community in the Modern West. Harvard University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-674-03257-6. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Nixon, Virginia (2004). Mary's Mother: Saint Anne in Late Medieval Europe. Penn State Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-271-02466-0. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Wood, Christopher S.; Wood, Professor Christopher S. (15 August 2008). Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art. University of Chicago Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-226-90597-6. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Bastress-Dukehart, Erica (19 August 2021). The Zimmern Chronicle: Nobility, Memory, and Self-Representation in Sixteenth-Century Germany. Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-351-88018-3. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Muller, Richard A.; Thompson, John L. (20 August 2020). Biblical Interpretation in the Era of the Reformation: Essays Presented to David C. Steinmetz in Honor of His Sixtieth Birthday. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-7252-8377-0. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Gooch, George Peabody (1901). Annals of Politics and Culture (1492-1899). The University Press. p. 13. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Ocker, Christopher (2007). Politics and Reformations: Histories and Reformations : Essays in Honour of Thomas A. Brady, Jr. BRILL. p. 161. ISBN 978-90-04-16172-6. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Thompson, James Westfall; Holm, Bernard J. (1967). A History of Historical Writing: From the earliest times to the end of the seventeenth century. P. Smith. p. 524. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Rabasa, José; Sato, Masayuki; Tortarolo, Edoardo; Woolf, Daniel (29 March 2012). The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 3: 1400-1800. OUP Oxford. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-19-162944-0. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Fichtner 2014, p. 75.

- ^ Kneupper, Frances Courtney (10 March 2016). The Empire At The End Of Time. Oxford University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-19-027937-0. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Routledge Library Editions: German History. Routledge. 14 July 2021. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-000-39807-6. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Smith 2014, p. 257.

- ^ Golubeva, 2013 & 55–70.

- ^ Rabasa et al. 2012, p. 308.

- ^ Esteve, Cesc (9 March 2018). Disciplining History: Censorship, Theory and Historical Discourse in Early Modern Spain. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-317-14997-2. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Seton-Watson 1902, p. 105.

- ^ Knoch, Wassili Ivanovic (1950). Vienna: The Capital of Music, Volume 6. Wolfrum in Komm. p. 28. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021."Maximilian was responsible for the reputation which Vienna enjoyed as the greatest musical centre of the Middle Ages"

- ^ Fichtner 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Potter 2014, p. 320.

- ^ Kelber, Moritz (2018). Die Musik bei den Augsburger Reichstagen im 16. Jahrhundert (PDF). Allitera Verlag. p. 33. ISBN 9783962330958. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Coelho, Victor; Polk, Keith (2016). Instrumentalists and Renaissance Culture, 1420-1600: Players of Function and Fantasy. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9781107145801. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Weaver, Andrew H. (2020). A Companion to Music at the Habsburg Courts in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. BRILL. p. 24. ISBN 9789004435032. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ Lerner, Edward R. (1975). "Review. Reviewed Work(s): The Emperor Maximilian I and Music by Louise Cuyler". The Musical Quarterly. 61 (1): 139. JSTOR 741689. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ Carreras Lopez, Juan José; García García, Bernardo José; Knighton, Tess (2005). The Royal Chapel in the Time of the Habsburgs: Music and Ceremony in Early Modern European Court. Boydell Press. p. 40. ISBN 9781843831396. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Cuyler 1973, pp. 41–53.

- ^ Wegman, Rob C. (2000). "Who was Josquin?". In Sherr, Richard (ed.). The Josquin Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-19-816335-0. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Burn, David Joseph (2002). The Mass-proper Cycles of Henricus Isaac: Text. University of Oxford. p. 45. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Rothenberg, David J. (1 January 2011). "The Most Prudent Virgin and the Wise King:Isaac's Virgo prudentissima Compositions in the Imperial Ideology of Maximilian I". Journal of Musicology. 28 (1): 36, 40, 45, 46, 67, 79. doi:10.1525/jm.2011.28.1.34.

- ^ Ross, Jill; Akbari, Suzanne Conklin (1 January 2013). The Ends of the Body: Identity and Community in Medieval Culture. University of Toronto Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-4426-4470-0. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Silver, Larry (2008). Marketing Maximilian: The Visual Ideology of a Holy Roman Emperor. Princeton University Press. p. 235. ISBN 9780691130194. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ MacGregor, Neil (2014). Germany: Memories of a Nation. Penguin UK. p. 316. ISBN 9780241008348. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Whaley 2009.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

oeawwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ylä-Anttila, pp. 7, 20, 24, 32, 151, 152.

- ^ Golubeva, Maria (20 May 2013). Models of Political Competence: The Evolution of Political Norms in the Works of Burgundian and Habsburg Court Historians, c. 1470-1700. BRILL. p. 52. ISBN 978-90-04-25074-1. Retrieved 13 November 2021.