User:Blun69690

Life[edit]

Langston Hughes was born James Mercer Langston Hughes in Joplin, Missouri, the son of Carrie Langston Hughes, a teacher, and her husband, James Nathaniel Hughes. After abandoning his family and the resulting legal dissolution of the marriage later, James Hughes left for Cuba first, then Mexico due to enduring racism in the United States. After the separation of his parents, young Langston was left to be raised mainly by his grandmother, Mary Langston, as his mother sought employment. Through the black American oral tradition of storytelling, she would instill in the young Langston Hughes a sense of indelible racial pride.[1][2][3] He spent most of childhood in Lawrence, Kansas. After the death of his grandmother, he went to live with family friends, James and Mary Reed, for two years. His childhood was not an entirely happy one, due to an unstable early life, but it was one that heavily influenced the poet he would become. Later, he lived again with his mother in Lincoln, Illinois who had remarried when he was still an adolescent, and eventually in Cleveland, Ohio where he attended high school.

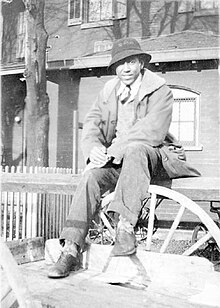

While in grammar school in Lincoln, Illinois, he was designated class poet because of, Hughes said later as an adult, his race, African Americans then being stereotyped as having rhythm.[4] "I was a victim of a stereotype. There were only two of us Negro kids in the whole class and our English teacher was always stressing the importance of rhythm in poetry. Well, everyone knows — except us — that all Negroes have rhythm, so they elected me as class poet."[5] During high school in Cleveland, Ohio, he wrote for the school paper, edited the yearbook, and began to write his first short stories, poetry, and dramatic plays. His first piece of jazz poetry, When Sue Wears Red, was written while he was still in high school. It was during this time that he discovered his love of books. From this early period in his life, Hughes would cite as influences on his poetry the American poets Paul Laurence Dunbar and Carl Sandburg. Hughes spent a brief period of time with his father in Mexico in 1919. The relationship between him and his father was troubled, causing Hughes a degree of dissatisfaction that led him to contemplate suicide at least once. Upon graduating from high school in June of 1920, Hughes returned to live with his father, hoping to convince him to provide money to attend Columbia University. Hughes later said that, prior to arriving in Mexico again, "I had been thinking about my father and his strange dislike of his own people. I didn't understand it, because I was a Negro, and I liked Negroes very much."[6][7][8] Initially, his father hoped for Langston to attend a university anywhere but in the United States, and to study for a career in engineering. On these grounds, he was willing to provide financial assistance to his son. James Hughes did not support his son's desire to be a writer. Eventually, Langston and his father came to a compromise. Langston would study engineering so long as he could attend Columbia. His tuition provided, Hughes left his father after more than a year of living with him. While at Columbia in 1921, Hughes managed to maintain a B+ grade average. He left in 1922 because of racial prejudice within the institution, and his interests revolved more around the neighborhood of Harlem than his studies, though he continued writing poetry. [[:Image:Langston_Hughes_by_Nickolas_Muray.jpg|thumb|left|Langston Hughes, photographed by Nickolas Muray, 1923]] Hughes worked various odd jobs before serving a brief tenure as a crewman aboard the S.S. Malone in 1923, spending 6 months traveling to West Africa and Europe.[9]In Europe, Hughes left the S.S. Malone for a temporary stay in Paris. Unlike specific writers of the post-World War I era who became identified as the Lost Generation, writers such as Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, Hughes instead spent time in Paris during the early 1920s becoming part of the black expatriate community. In November 1924 Hughes returned to the U. S. to live with his mother in Washington, D.C. Hughes again found work doing various odd jobs before gaining white-collar employment in 1925 as a personal assistant to the scholar Carter G. Woodson within the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. Not satisfied with the demands of the work and time constraints this position with Carter placed on the hours he spent writing, Hughes quit this job for one as a busboy in a hotel. It was while working as a busboy that Hughes would encounter the poet Vachel Lindsay. Impressed with the poems Hughes showed him, Lindsay publicized his discovery of a new black poet, though by this time Hughes' earlier work had already been published in magazines and was about to be collected into his first book of poetry.

The following year, Hughes enrolled in Lincoln University, PA, a HBCU.[10][11] Hughes received a B.A. degree from Lincoln University in 1929 and a Litt.D. in 1943 from Lincoln. A second honorary doctorate would be awarded to him in 1963 by Howard University, another HBCU. Except for travels that included parts of the Caribbean and West Indies, Harlem was Hughes’s primary home for the remainder of his life.

On May 22, 1967, Hughes died from complications after abdominal surgery related to prostate cancer at the age of 65. His ashes are interred beneath a floor medallion in the middle of the foyer leading to the auditorium named for him within the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem.[12] Many of Langston Hughes' personal papers reside in the Langston Hughes Memorial Library on the campus of Lincoln University as well as at the James Weldon Johnson Collection within the Yale University Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Bibliography[edit]

Poetry

- The Weary Blues. Knopf, 1926

- Fine Clothes to the Jew. Knopf, 1927

- The Negro Mother and Other Dramatic Recitations, 1931

- Dear Lovely Death, 1931

- The Dream Keeper and Other Poems. Knopf, 1932

- Scottsboro Limited: Four Poems and a Play. N.Y.: Golden Stair Press, 1932

- Shakespeare in Harlem. Knopf, 1942

- Freedom's Plow. 1943

- Fields of Wonder. Knopf,1947

- One-Way Ticket. 1949

- Montage of a Dream Deferred. Holt, 1951

- Selected Poems of Langston Hughes. 1958

- Ask Your Mama: 12 Moods for Jazz. Hill & Wang, 1961

- The Panther and the Lash: Poems of Our Times, 1967

- The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. Knopf, 1994

- Let America be America Again, 2004

Fiction [[Image:NonFreeImageRemoved.svg -->|thumb|The Best of Simple by Langston Hughes, 1961. Photograph courtesy of Yale University Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library]]

- Not Without Laughter. Knopf, 1930

- The Ways of White Folks. Knopf, 1934

- Simple Speaks His Mind. 1950

- Laughing to Keep from Crying, Holt, 1952

- Simple Takes a Wife. 1953

- Sweet Flypaper of Life, photographs by Roy DeCarava. 1955

- Simple Stakes a Claim. 1957

- Tambourines to Glory (book), 1958

- The Best of Simple. 1961

- Simple's Uncle Sam. 1965

- Something in Common and Other Stories. Hill & Wang, 1963

- Short Stories of Langston Hughes. Hill & Wang, 1996

Non-Fiction

- The Big Sea. New York: Knopf, 1940

- Famous American Negroes. 1954

- Marian Anderson: Famous Concert Singer. 1954

- I Wonder as I Wander. New York: Rinehart & Co., 1956

- A Pictorial History of the Negro in America, with Milton Meltzer. 1956

- Famous Negro Heroes of America. 1958

- Fight for Freedom: The Story of the NAACP. 1962

Major Plays

- Mule Bone, with Zora Neale Hurston. 1931

- Mulatto. 1935 (renamed The Barrier, an opera, in 1950)

- Troubled Island, with William Grant Still. 1936

- Little Ham. 1936

- Emperor of Haiti. 1936

- Don't You Want to be Free? 1938

- Street Scene, contributed lyrics. 1947

- Tambourines to glory. 1956

- Simply Heavenly. 1957

- Black Nativity. 1961

- Five Plays by Langston Hughes. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1963.

- Jericho-Jim Crow. 1964

Works for Children

- Popo and Fifina, with Arna Bontemps. 1932

- The First Book of the Negroes. 1952

- The First Book of Jazz. 1954

- The First Book of Rhythms. 1954

- The First Book of the West Indies. 1956

- First Book of Africa. 1964

Other

- The Langston Hughes Reader. New York: Braziller, 1958.

- Good Morning Revolution: Uncollected Social Protest Writings by Langston Hughes. Lawrence Hill, 1973.

- The Collected Works of Langston Hughes. Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2001.

- ^ Hughes recalled his maternal grandmother’s stories: "Through my grandmother’s stories life always moved, moved heroically toward an end. Nobody ever cried in my grandmother’s stories. They worked, schemed, or fought. But no crying." Rampesad, Arnold & Roessel, David (2002). The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. p.620

- ^ The poem Aunt Sues’s Stories (1921) is an oblique tribute to his grandmother and his loving Auntie Mary Reed. Rampersad.vol.1, 1986, p.43

- ^ Imbued by his grandmother with a duty to help his race, he identified with neglected and downtrodden blacks all his life, and glorified them in his work. Brooks, Gwendolyn, (Oct. 12, 1986). The Darker Brother. The New York Times

- ^ Langston Hughes Reads his poetry with commentary, audiotape from Caedmon Audio

- ^ Langston Hughes, Writer, 65, Dead. (May 23, 1967). The New York Times

- ^ Langston Hughes, The Big Sea (1940), pp.54-56

- ^ James Hughes, a wealthy lawyer and landowner and himself a black man, hated both the racism of the North and Negroes, whom he portrayed in crude racial caricature. Smith, Dinitia (Nov. 26, 1997). Child’s Tale About Race Has a Tale of Its Own. The New York Times

- ^ And the father, Hughes said, "hated Negroes. I think he hated himself, too, for being a Negro. He disliked all of his family because they were Negroes." James Hughes was tightfisted, uncharitable, cold. Brooks, Gwendolyn, (Oct. 12, 1986). The Darker Brother. The New York Times

- ^ Poem or To.F.S. first appeared in The Crisis in May 1925, and was reprinted in The Weary Blues and The Dream Keeper. Hughes never publicly identified F.S., but it is conjectured he was Ferdinand Smith, a merchant seaman whom the poet first met in New York in the early 1920s. Nine years older than Hughes, Smith first influenced the poet to go to sea. Born in Jamiaca in 1893, Smith spent most of his life as a ship steward and political activist at sea--and later in New York as a resident of Harlem. Smith was deported back to Jamaica for alleged Communists activities and illegal alien status in 1951. Hughes corresponded with Smith up until 1961 when Smith died. Berry,p.347

- ^ In 1926, a patron of Hughes, Amy Spingarn, wife of Joel Elias Spingarn, provided the funds ($300) for him to attend Lincoln University. Rampersad.vol.1, 1986,p.122-23

- ^ In November of 1927, Charlotte Osgood Mason, “Godmother” as she liked to be called, became Hughes' major patron. Rampersad. vol.1,1986,p.156

- ^ Whitaker, Charles.Ebony magazine In Langston Hughes:100th birthday celebration of the poet of black America. April 2002.