User:Baltaci/Dobruja2

Dobruja, or Dobrudja ([Добруджа, Dobrudzha] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help); Romanian: Dobrogea; Turkish: Dobruca; [Δοβρουτσά, Dovroutsá] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)), is a historical region shared by Bulgaria and Romania, located between the lower Danube river and the Black Sea.

Geography[edit]

Limits[edit]

The toponym "Dobruja" generally refers to the historically steppe region between the lower Danube to the west and the Black Sea to the east. The northern, and especially the southern borders have varied in time, and several authors proposed different alignments based on geographical, geological or biogeographical criteria. However, political borders in the region generally have ignored such limits. In modern usage, the term Dobruja applies to the territories awarded to Romania by the 1878 Treaty of Berlin ("Northern Dobruja", the modern Romanian counties of Constanţa and Tulcea) and the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest ("Southern Dobruja", the modern Bulgarian counties of Dobrich and Silistra).

In Late Antiquity, when the region became a separate Roman province (under the name of Scythia), it extended to the North to the Danube mouths, while in the South it was separated from the province of Moesia Secunda by a line connecting a point on the Danube east of Lake Oltina and the mouth of the river Zyras (Batova), on the Black Sea,[1] thus including most of the Romanian part of Dobruja and most of the province of Dobrich in Bulgaria.

The first clear delimitation of the region under its modern name was made by the 17th century Ottoman geographer Hadji Khalfa, who included in Dobruja all the land between the lower Danube and the Black Sea to a line connecting Silistra on the Danube and Aytos on the Black Sea in the south. Specifically, he mentioned the kadiliks (judicial districts) of Umurfakı, Aytos, Babadag, Techirghiol, Isaccea, Măcin, Hârşova, Çardak, Provadiya, Shumen, Hacıoğlu Pazarcık and Kara Ağaç as part of the region, while excluding the town of Razgrad.[2] Thus, the toponym "Dobruja" covered all the lands ruled by despot Dobrotitsa at the height of his power in the late 14th century. The territory such named extended much South of the modern use, including, besides the Romanian Dobruja and the Bulgarian province of Dobrich, most of the province of Varna, as well as important parts of of the provinces of Silistra, Shumen and Burgas. Hadji Khalfa is also the first to mention that Dobruja borders to the south the region of Deliorman (known nowadays as Ludogorie).[3]

The southern limit is not as clear, the ill-defined Deliorman (modern Ludogorie) serving as its traditional southern border. In the early 19th century, the steppe, Dobruja-Kırı, extended between the forests around Babadag in the north and the Balkans to the south. Eventually, the term was extended to include the northern part and the Danube Delta.[4]

The elusive southern limit differs from author to author. The 17th century Ottoman geographer Hadji Khalfa put it on the Silistra–Aitos line. In the 19th century, Bulgarian Paluzoff put in on the Silistra–Varna line, while French author Camile Allard used the Silitra–Dobrich–Balchik line.[5] British engineer Th. Forester put it even far northern, on the Carasu Valley (nowadays the Danube-Black Sea Canal) ( while considering the southernmost branch of the Danube as its northern limit).[6] According to the 1916 account of the Bulgarian historian Dr Ischirkoff, the local population considered the southern border to be on the Oltina–Korkut–Halatchy–Batovo River line. In 1918, Dr Ischirkoff gave a slightly different limit: Lake Gârliţa–Tsani Ginchevo–Yabulkovo (near Vladimirovo)–Banovo–Lake Devnya–Euxinograd. Beginning with 1913 Dobruja is often used to refer the region awarded to Romania by the treaties of Berlin (1878) and Bucharest (1913), with the southern limit on the Nova Cherna–Kranevo line, even if this definition also includes parts of the historical regions of Deliorman and Batovo. The southern limits of the modern Silistra and Dobrich districts follow this general line, and this definition will be adopted in the rest of the article.

Relief[edit]

With the exception of the Danube Delta, a marshy region located in its north‑eastern corner, Dobruja is hilly, with an average altitude of about 200–300 metres. The highest point is in the Ţuţuiatu (Greci) Peak in the Măcin Mountains, having a height of 467 m. The Dobrogea Plateau covers most of the Romanian part of Dobruja, while in the Bulgarian part the Ludogorie Plateau is found. Lake Siutghiol is one of the most important lakes in Northern Dobruja.

Climate[edit]

Dobruja lies in the temperate continental climatic area; the local climate is determined by the influx of oceanic air from the north‑west and north‑east and continental air from the East European Plain. Dobruja's relatively level terrain and its bare location facilitate the influx of humid, warm air in the spring, summer and autumn from the north‑west, as well as that of northern and north‑eastern polar air in the winter. The Black Sea also exerts an influence over the region's climate, particularly within 40–60 kilometres from the coast. The average annual temperatures range from 11 °C inland and along the Danube to 11.8 °C on the coast and less than 10 °C in the higher parts of the plateau. The coastal region of Southern Dobruja is the most arid part of Bulgaria, with an annual precipitation of 450 millimetres.

Dobruja is a windy region once known for its windmills. About 85–90% of all days experience some kind of wind, which usually comes from the north or north‑east. The average wind speed is about twice higher than the average in Bulgaria. Due to the limited precipitation and the proximity to the sea, rivers in Dobruja are usually short and with low discharge. However, the region has a number of shallow seaside lakes with brackish water.[7]

Etymology[edit]

The most widespread opinion among scholars is that the origin of the term Dobruja is to be found in the Turkish rendition of the name of a 14th‑century ruler, despot Dobrotitsa.[8] It was common for the Turks to name countries after one of their early rulers (for example, nearby Moldavia was known as Bogdan Iflak by the Turks, named after Bogdan I).[4] Other etymologies have been considered, but never gained widespread acceptance. Abdolonyme Ubicini believed the name meant "good lands", derived from Slavic dobro ("good"), an opinion that was adopted by several 19th‑century scholars.[9] This view, which contrasts with the usual 19th‑century description of Dobruja as a dry barren land, has been explained as the point of view of Ruthenes, who saw the Danube delta in the northern Dobruja as a significant improvement over the steppes to the north. A version matching contemporaneous descriptions was suggested by Kanitz, who connected the name with the Slavic dobrice ("rocky and unproductive terrain").[10] According to Gheorghe I. Brătianu, the name is a Slavic derivation from a Turkic word (Bordjan or Brudjars) which referred to the Turkic Proto-Bulgarians, term also used by Arabic writers.[11]

Various names were used during history to refer to the territory between the Danube and Black Sea. The oldest known is Mikra Skythia (Greek for "Lesser Scythia"), first documented in the works of Strabo, and afterwards used by various authors, sometimes under the Latin form Scythia Minor. The name was a reference to the Scythian tribes who entered the region in the 6th century BC, and was used to differentiate the region from their original homeland, Greater Scythia, in the steppes north of the Black Sea. When the region became a distinct administrative division of the Roman Empire, during Diocletian's rule, the name of the new province was simply Scythia.[12] This designation was lost after Dobruja fell under Bulgarian rule, and only in the 10th century the region was again considered a separate region, referred to by the Byzantines as Paristrion or Paradunavon("near the Danube", probably a calque after Slavic po Dunavie). This term also fell from use by the 12th century.[13]

The earliest uses of the name Dobruja can be found in 15th century works by Ottoman Turkish historians. In the Oghuz-name narrative, authored by Yazijioghlu 'Ali (1421-1451), the region appears as Dobruja-éli, the possessive suffix el-i indicating that the land was considered as belonging to Dobrotitsa ("دوبرجه" in the original Ottoman Turkish).[14] The loss of the final particle is not unusual in the Turkish world, a similar evolution being observed in the name of Aydın, originally Aydın-éli.[15] The name Sahra-i Dobruǧa ("Plains of Dobruja") was another early name used by Turkish writers.[16] In European languages, an early use is in the 16th‑century Latin translation of Laonicus Chalcondyles' Histories, where the term Dobroditia is used for the original Greek "Dobrotitsa's country" (Δοβροτίκεω χώρα).[17] Beginning with the 17th century the name became more common, with renditions such as Dobrucia, Dobrutcha, Dobrus, Dobruccia, Dobroudja, Dobrudscha and others being used by foreign authors.[18]

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]

The first signs of human habitation in Dobruja have been dated to the late Cromerian period of Lower Palaeolithic (ca. 700,000 BP), and are represented by several chipped stone tools found in a cave near Gura Dobrogei, in the centre of the region.[19][20] Artefacts (mainly stone tools) become more common in the Middle Palaeolithic, when a rise in the temperature during the Würm glaciation led to a growth in the human population. The tools, specific to the Mousterian culture, have been attributed to Neanderthals living in a wooded landscape. The main sites are Mamaia-Sat (considered to be the oldest Mousterian site in Dobruja, and probably in Romania), Castelu, Cuza Vodă, the La Izvor cave near Târguşor, and the high Danube terrace at Tutrakan.[21] Upper Palaeolithic brought a diversification in tools, with new artefacts, such as microlites and bone tools, being found on the Danube's terraces and in the La Izvor and La Adam caves on the Casimcea valley. The latter is also the site were the oldest human fossils in Dobruja have been found: a tooth bud, attributed to Homo sapiens fossilis, located in an Aurignacian medium. During the Epipalaeolithic and Mesolithic, following the end of the last glaciation, the Dobrujan landscape gradually acquired a semi-arid steppe character, which came to dominate the ensuing history of the area. The change led to a decline in large game, and consequently to a drop in the human population.[22] The Epipalaeolithic sites at Gherghina and Castelu are attributed to an Epigravettian horizon that extended into southern Moldavia.[23] In the Mesolithic (9,000-7,000 BP), the region was inhabited by a hunter-gatherer population, integrated in a north-western Pontic subtype of Tardenoisian. Their sites, at Medgidia and Straja, show extensive similarities with contemporaneous sites east of the Pruth, and may have been under Crimean influence.[24]

In contrast with the neighbouring regions, the Dobrujan early Neolithic (6600-5500 BC) is marked by a lack of archaeological discoveries, the causes thereof still not fully understood. It is assumed that this hiatus was caused, at least partially, by a major rise in the Black Sea level,[25] associated by some scholars with the Black Sea deluge theory.[26]

In the Neolithic, it was part of the Hamangia culture (named after a village on the Dobrujan coast), Boian culture and Karanovo V culture. At the end of the fifth millennium BC, under the influence of some Aegeo-Mediterranean tribes and cultures, the Gumelniţa culture appeared in the region. In the Eneolithic, populations migrating from the north of the Black Sea, of the Kurgan culture, mixed with the previous population, creating the Cernavodă I culture. Under Kurgan II influence, the Cernavodă II culture emerged, and then, through the combination of the Cernavodă I and Ezero cultures, developed the Cernavodă III culture. The region had commercial contacts with the Mediterranean world since the 14th century BC, as a Mycenaean sword discovered at Medgidia proves.[27]

Ancient history[edit]

The early Iron Age (8th–6th centuries BC) saw an increased differentiation of the local Getic tribes from the Thracian mass. In the second part of the 8th century BC, the first signs of commercial relations between the indigenous population and the Greeks appeared on the shore of the Halmyris Gulf (now the Sinoe Lake). In 657/656 BC colonists from Miletus founded the first colony in the region—Histria.[28] In the 7th and 6th centuries BC, more Greek colonies were founded on the Dobrujan coast (Callatis, Tomis, Mesembria, Dionysopolis, Parthenopolis, Aphrodisias, Eumenia etc). In the 5th century BC these colonies were under the influence of the Delian League, passing in this period from oligarchy to democracy.[29][dead link] Furthermore, in the 6th century BC, the first Scythian groups began to enter the region. Two Getae tribes, the Crobyzi and Terizi, and the town of Orgame (Argamum) were mentioned on the territory of present Dobruja by Hekataios of Miletus (540–470 BC).[30]

In 514/512 BC King Darius I of Persia subdued the Getae living in the region during his expedition against Scythians living north of the Danube.[31] At about 430 BC, the Odrysian kingdom under Sitalkes extended its rule to the mouths of the Danube.[32] In 429 BC, Getae from the region participated in an Odrysian campaign in Macedonia.[33] In the 4th century BC, the Scythians brought Dobruja under their sway. In 341–339 BC, one of their kings, Atheas fought against Histria, which was supported by a Histrianorum rex (probably a local Getic ruler). In 339 BC, King Atheas was defeated by the Macedonians under King Philip II, who afterwards extended his rule over Dobruja.[34]

In 313 BC and again in 310–309 BC the Greek colonies led by Callatis, supported by Antigonus I Monophthalmus, revolted against Macedonian rule. The revolts were suppressed by Lysimachus, the diadochus of Thracia, who also began a military expedition against Dromichaetes, the ruler of the Getae north of the Danube, in 300 BC. In the 3rd century BC, colonies on the Dobrujan coast paid tribute to the basilei Zalmodegikos and Moskon, who probably ruled also northern Dobruja. In the same century, Celts settled in the north of the region. In 260 BC, Byzantion lost the war with Callatis and Histria for the control of Tomis. At the end of the 3rd century BC and the beginning of the 2nd century BC, the Bastarnae settled in the area of the Danube Delta. Around 200 BC, the Thracian king Zoltes invaded the province several times, but was defeated by Rhemaxos, who became the protector of the Greek colonies.

Around 100 BC King Mithridates VI of Pontus extended his authority over the Greek cities in Dobruja. However, in 72–71 BC, during the Third Mithridatic War, these cities were occupied by the Roman proconsul of Macedonia, Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus. A foedus was signed between the Greek colonies and the Roman Empire, but in 62–61 BC the colonies revolted. Gaius Antonius Hybrida intervened, but was defeated by Getae and Bastarnae near Histria. After 55 BC the Getae King Burebista conquered Dobruja and all the Greek colonies on the coast, but his polity dissolved after his death in 44 BC.

Roman rule[edit]

In 28/29 BC Rholes, a Getic ruler from southern Dobruja, supported the proconsul of Macedonia, Marcus Licinius Crassus, in his action against the Bastarnae. Declared Socius et amicus Populi Romani by Octavian,[35] Rholes helped Crassus in conquering the Getae tribes of Dapyx (in central Dobruja) and Zyraxes (in the north of the region).[36] Dobruja became part of the client kingdom of the Odrysians, while the Greek cities on the coast came under direct rule of the governor of Macedonia. In 12 AD and 15 AD, Getic armies succeeded in conquering the cities of Aegyssus and Troesmis for a short time, but Odrysian king Rhoemetalces defeated them with the help of the Roman army.

In 15 AD the Roman province of Moesia was created, but Dobruja, under the name Ripa Thraciae remained part of the Odrysian kingdom, while the Greek cities on the coast was organised as a Praefectura orae maritimae, subordinated to the governor of Macedonia. In 46 AD Thracia became a Roman province and the territories of present Dobruja were absorbed into the province of Moesia. The Getae, Sarmatians and Dacians invaded the region several times in the 1st century AD, especially between 62 and 70. In the same period, the base of the Roman Danube fleet (classis Flavia Moesica) was moved to Noviodunum. The praefectura was annexed to Moesia in 86 AD. In the same year Domitian divided Moesia, Dobruja being included in the eastern part, Moesia Inferior.

In the winter of 101–102 the Dacian king Decebalus led a coalition of Dacians, Carpians, Sarmatians and Burs in an attack against Moesia Inferior. The invading army was defeated by the Roman legions under Emperor Trajan on the Yantra river (later Nicopolis ad Istrum was founded there to commemorate the victory), and again near modern village of Adamclisi, in the southern part of Dobruja. The latter victory was commemorated by a monument, built in 109 on the spot and the founding of the city of Tropaeum. After 105, Legio XI Claudia and Legio V Macedonica were moved to Dobruja, at Durostorum and Troesmis respectively.

In 118 Hadrian intervened in the region to calm a Sarmatian rebellion. In 170 Costoboci invaded Dobruja, attacking Libida, Ulmetum and Tropaeum. The province was generally stable and prosperous until the crisis of the Third Century, which led to the weakening of defences and numerous barbarian invasions. In 248 a coalition of Goths, Carpians, Taifali, Bastarnae and Hasdingi, led by Argaithus and Guntheric devastated Dobruja.[37] During the reign of Trajan Decius the province suffered greatly from the attack of Goths under King Cniva.[38] Barbarian attacks followed in 258, 263 and 267. In 269 a fleet of allied Goths, Heruli, Bastarnae and Sarmatians attacked the cities on the coast, including Tomis.[39] In 272 Aurelian defeated the Carpians north of the Danube and settled a part of them near Carsium. The same emperor put an end to the crisis in the Roman Empire, thus helping the reconstruction of the province.

During the reign of Diocletian Dobruja became a separate province, Scythia, part of the Diocese of Thracia. Its capital city was Tomis. Diocletian also moved Legio II Herculia to Troesmis and Legio I Iovia to Noviodunum. In 331–332 Constantine the Great defeated the Goths who attacked the province. Dobruja was devastated again by Ostrogoths in 384–386. Under the emperors Licinius, Julian the Apostate and Valens the cities of the region were repaired or rebuilt. The 3rd and 4th centuries also saw the widespread adoption of Christianity by the local population,[40] whose introduction in the region is attributed by tradition to Saint Andrew.

Byzantine rule[edit]

After the division of the Roman Empire, Dobruja became part of the Eastern Roman Empire. By the 6th century a fairly developed Christian hierarchy had evolved, with 15 dioceses attested.[41] Between 513 and 520, the region participated in a revolt against Anastasius I. Its leader, Vitalianus, native of Zaldapa, in Southern Dobruja, succeeded in defeating the Byzantine general Hypatius near Kaliakra. During Justin I's rule, Antes and Slavs invaded the region, but Germanus Justinus defeated them. In 529, the Gepid commander Mundus repelled a new invasion by Bulgars and Antes. Kutrigurs and Avars invaded the region several times, until 561–562, when the Avars under Bayan I were settled south of the Danube as foederati. During the rule of Maurice, the Slavs devastated Dobruja, destroying the cities of Dorostolon, Zaldapa and Tropaeum. In 591/593, Byzantine general Priscus tried to stop invasions, attacking and defeating the Slavs under Ardagast in the north of the province.

In 602, during Maurice's winter campaign against the Avars north of the Danube, the Byzantine army mutinied, marched against Constantinople and overthrew the emperor. The new developments , as well as the new emperor's focus on the war in the east against the Persians, reduced the effectiveness of the Danube limes, allowing Slavs to penetrate in Byzantine territories.[42] In Dobruja, Slavs settled mostly on the Black Sea coast and on the Danube bank. The following decades saw a decrease in Byzantine authority over the region, reorganised during the reign of Constantine IV as Thema Scythia, correlated with a important drop in the population and a gradual ruralisation of Dobrujan cities.[43] Some of the forts, destroyed by the successive invasions, were completely abandoned, Durostorum being the only one able to preserve its urban status.[44][45] During this period a Turkic political centre, protected by an earthen wall system, emerged near Niculiţel, in the northern part of Dobruja. The site, dated by various authors from the 5th to the 8th century, may have been built by a group of Kubrat’s Bulgars, employed by the Byzantines to undermine the power of the Avar Khaganate north of the Danube.[46]

First Bulgarian Empire[edit]

In the late 7th century, under Khazar pressure, the Bulgars led by Asparukh left the North-pontic steppe and settled near the Danube, in the immediate vicinity of Dobruja, and started raiding the Byzantine territories south of the Danube. The territory were they settled, called "Oglos" or "Onglos", is generally placed north of the Danube, although in the past some Bulgarian authors suggested a location in Northern Dobruja, either at Niculiţel, or in a larger area north of the smallest of the Dobrujan Trajan’s walls. [46][47]

The Byzantines, seeking to put a stop to the raids, attacked the Onglos in 680, however they were defeated in the ensuing battle and were forced to accept a peace treaty, recognising the authority of the new Bulgar state over the lands between the Balkan Mountains and the Danube. The main area of concentration of Bulgar population was the north-east of modern Bulgaria, including parts of Dobruja.[48][49][50] While the Slavs earlier settled the northern and western part of Dobruja (such as near the current villages of Gărvan, Capidava, Piatra Frecăţei, Popina, Nova Cherna, Staro selo), the Turkic Bulgars settled mainly in the South(near Kladentsi, Tsar Asen, Topola and especially near Durankulak).[51] Early mediaeval Bulgar stone inscriptions were found in several regions of Dobruja, including historical narratives, inventories of armament or buildings and commemorative texts, but their importance is disputed among Bulgarian and Romanian historians.[52][53]

According to the Bulgarian Apocryphal Chronicle, from the 11th century, Bulgar ruler Ispor (Asparukh) "accepted the Bulgarian tsardom", built "great cities, Drastar on the Danube", a "great wall from Danube to the sea", "the city of Pliska" and "populated the lands of Karvuna".[54] However, none of the mentioned constructions could be archaeologically attributed to the time of Asparukh,[55] and most Romanian historians consider that the chronicle has a purely legendary character.[56] Only in the late eight century the Bulgar khan’s residence was established at Pliska, in the vicinity of Dobruja,[57][55] and nearby Madara developed as a major Bulgarian pagan religious centre.[58] According to Bulgarian historians, during the 7th–10th centuries, the region was embraced by a large net of earthen and wooden strongholds and ramparts.[59] The Bulgarian origin of the ramparts is generally disputed by Romanian historians, who consider that the construction system and archaeological evidence are not consistent with this attribution. Beginning with the end of the 8th century, numerous new stone fortresses and defensive walls were erected across the Bulgarian Empire,[60] and even some of the ruined Byzantine fortresses were rebuilt (Kaliakra and Silistra in the 8th century, Madara and Varna in the 9th) to strengthen the defensive system in the region of Dobruja.[61] According to an inscription kept in SS. Forty Martyrs Church in Veliko Tarnovo, in the early 9th century, Khan Omurtag built a "glorious home on Danube" and erected a mound in the middle of the distance between Pliska and his new building. The location of this edifice remains unclear; the main theories locating it at Silistra or at Păcuiul lui Soare.[62][63] In the 10th century and early 11th century, Murfatlar, in central Dobruja, became the site of an important Christian monastic centre, under the protection of local feudal lords such as zhupan George.

The Dobrujan coast and the mouths of the Danube remained an area of operation for the Byzantine navy, with a fleet of 500 ships mentioned on the Danube in 756.[64] At the beginning of the 8th century, Justinian II visited Dobruja to ask Bulgarian Khan Tervel for military help. In the 9th century a Byzantine protospatharios is mentioned at Lykostomion, while in 917 the Byzantine fleet is again attested at the Danube, under droungarios Romanos. Romanian historians claim, based on archaeological finds, that the Byzantines also controlled some Dobrujan forts between the 8th and 10th centuries, such as Dorostolon and Isaccea.[65] Bulgarian archaeologists dispute these conclusions.[66][45]

The Bulgarian rule didn't spare Dobruja from the invasions of the nomadic groups of the Pontic Steppe. Thus, in 895 Magyar tribes from Budjak invaded Dobruja and north‑eastern Bulgaria with Byzantine support, being eventually routed by the Bulgarians and their Pechenegs allies.[67] The oldest known old Slavic stone inscription, found at Mircea Vodă, mentions zhupan Dimitri (Дѣимитрѣ жѹпанѣ), a feudal landlord in the south of the region, who in 943 defeated an invader from the north.[68]

High Middle Ages[edit]

On Nikephoros II Phocas demand, in 968 Sviatoslav I of Kiev invaded the Bulgarian Empire, conquering "80 towns" in Dobruja and eastern Moesia, and moving the capital of Kievan Rus' to Pereyaslavets, at the mouths of the Danube. The new capital is described by the prince as "the hearth of the kingdom", an important commercial centre with goods flowing from all over Europe. In 971 Byzantines under John I Tzimisces claimed the region, and, after a three-months long siege at Dorostolon, they defeated Sviatoslav, reconquering Dobruja and including it in the Theme Mesopotamia of the West (Μεσοποταμια της Δυσεον).[69] The return of the Byzantines led to a revival of urban live, with the old Roman forts at Capidava, Axiopolis and Noviodunum being rebuilt, and a new fluvial fortress being founded at Păcuiul lui Soare.[70][71] The fate of Dobruja after the death of Tzimisces in 976 is disputed, historians disagreeing on whether the region remained in Byzantine hands or was included in the restored Bulgarian state of the Cometopuli. According to some historians soon after 976[72] or in 986, the southern part of Dobruja was included in the Bulgarian state of Samuil, while the northern part remained under Byzantine rule, being reorganised in an autonomous klimata.[73][74] According to other theories, supported mainly by Bulgarians scholars, Northern Dobruja was reconquered by Bulgarians as well,[75] still others, mainly Romanians, claiming that all Dobruja remained under Byzantine rule.[76] In 1000, a Byzantine army commanded by Theodorokanos reconquered the whole Dobruja,[77] organizing the region as Strategia of Dorostolon and, after 1020, as Thema Paristrion (Paradunavon). To prevent mounted attacks from the north, the Byzantines built or repaired the three ramparts extending from the Black Sea down to the Danube.[78] However, according to the Bulgarian archaeologists and historians, these fortifications are of an earlier date, being constructed by the First Bulgarian Empire against the threat of Khazar raids.[79][80]

Beginning with the 10th century, Byzantines accepted the settling of small groups of Pechenegs in Dobruja.[81] In the spring of 1036, an invasion of the Pechenegs devastated large parts of the region,[82][dead link] destroying the forts at Capidava and Dervent and burning the settlement in Dinogeţia. In 1046 the Byzantines accepted the settling of Pechenegs under Kegen in Paristrion as foederati.[83][dead link] They established some form of domination until 1059, when Isaac I Komnenos reconquered Dobruja. In 1064, the great invasion of the Uzes affected the region. In 1072–1074, when Nestor, the new strategos of Paristrion, came to Dristra, he found a ruler in rebellion there, Tatrys. In 1091, three autonomous, probably Pecheneg,[84] rulers were mentioned in the Alexiad: Tatos (Τατοῦ) or Chalis (χαλῆ) (probably the same as Tatrys)[85] in the area of Dristra, and Sesthlav (Σεσθλάβου) and Satza (Σατζά) in the area of Vicina.[86]

This section may contain information not important or relevant to the article's subject. |

Cumans came in Dobruja in 1094 and maintained an important role until the advent of the Ottoman Empire.[87] In 1187 the restored Bulgarian Empire may have extended its authority over Dobruja, although no conclusive evidence has been found.[88] In 1241, the first Tatar groups, under Kadan, invaded Dobruja starting a century long history of turmoil in the region.[89][90] In 1263–1264, Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus gave permission to Sultan Kaykaus II to settle in the area with a group of Seljuk Turks from Anatolia.[91] A missionary Turkish mystic, Sarı Saltuk, was the spiritual leader of this group;[92] his tomb in Babadag (which was named after him)[93] is still a place of pilgrimage for the Muslims. That happened during the campaign of Michael Glabas Tarchaneiotes against Bulgaria.[94] A part of these Turks returned to Anatolia in 1307, while those who remained became Christianised and adopted the name Gagauz.[95][93] In the 1265 the Bulgarian Emperor Constantine Tikh Asen hired 20,000 Tatar to cross the Danube and attack Byzantine Thrace.[96][97] On their way back the Tatars forced most of the Seljuk Turks including their chief Sarı Saltuk to resettle in Kipchak (Cumania).[98][99] In the second part of the 19th century, the Turkic–Mongolian Golden Horde Empire continuously raided and plundered Dobruja.[100] The incapability of the Bulgarian authorities to cope with the numerous raids became the main reason for the uprising of Ivailo (1277–1280) which broke out in eastern Bulgaria.[101] Ivailo's army defeated the Tatars who were forced to leave the Bulgarian territory, then routed Constantine Tikh's army and Ivailo was crowned Emperor of Bulgaria. The war with the Tatars, however, raged—in 1278, after a new Tatar invasion in Dobruja, Ivailo was forced to retreat to the strong fortress of Silistra in which he withstood a three-month siege.[102] In 1280 the Bulgarian nobility, which feared the growing influence of the peasant emperor, organised a coup and Ivailo had to flee to his enemy the Tatar Nogai Khan, who later killed him.[103] In 1300 the new Khan of the Golden Horde Toqta ceded Bessarabia to Emperor Theodore Svetoslav.[104]

Autonomous despotate. Wars with the Ottomans[edit]

In the early 14th century a new polity started to develop in the area known as the Country of Karvuna in Southern Dobruja (the coast between Mangalia and Varna).[105] The polity slowly emancipated itself from central Bulgarian rule, and fell under Byzantine influence, an important step in this direction being the appointment in 1325 of a Metropolitan "of Varna and Carvona" by the Patriarch of Constantinople. Soon after, a local ruler, Balik/Balica,[106] is mentioned as participating in the disputes for the Byzantine throne. In 1346, he supported John V Palaeologus in the civil war against John VI Cantacuzenus by sending an army corps under Dobrotitsa/Dobrotici and his brother, Theodore, to help the mother of John Palaeologus, Anna of Savoy. For his bravery, Dobrotitsa/Dobrotici received the title of strategos and married the daughter of megadux Apokaukos.

After the reconciliation of the two pretenders, a territorial dispute broke out between the Dobrujan polity and the Byzantine Empire for the port of Midia. In 1347, on John V Palaeologus' demand, Emir Bahud-din Umur, Bey of Aydın, led a naval expedition against Balik/Balica, destroying Dobruja's seaports. Balik/Balica and Theodore died during the confrontations, Dobrotitsa/Dobrotici becoming the new ruler.[107]

Beginning with the late 13th century, the Genoese Republic established several commercial outpost on the Lower Danube and the Dobrujan coast. After their victory in the war against the Byzantines an their Venetian allies in the late 1340s, the Genoese also extended their rule over the important commercial centres of Vicina, Kilia and Lykostomo in the northern part of Dobruja, virtually controlling the commerce at the mouths of the Danube and in the northern Black Sea. This coincided with the expansion of Dobrotitsa's influence in the region, the commercial competition evolving into an armed conflict as early as 1360.[108]

However the conflict soon stalled, probably because of new political developments in the region. Thus, northern Dobruja witnessed a relapse of the Mongol rule, with a Tatar prince, Demetrius, claiming to be the protector of the mouths of the Danube after 1362/1363.[109] Also, in the south, a new conflict broke between the Tsardom of Tarnovo and the Byzantines in 1364-1365. Dobrotitsa probably sided with the Byzantines, the latter's victory giving him the occasion to expand his rule towards Varna. Another destabilizing element in the region was the growing influence of the Kingdom of Hungary, which reestablished its suzerainty over Wallachia, conquered Vidin and forged an alliance with Prince Demetrius. In 1366, John V Palaeologus visited Buda, Hungary's capital, trying to gather military support for his campaigns, but on his way home he was blocked at Vidin by Tsar Ivan Alexander, who considered that the new alliances were directed against his realm. As a reaction, an anti-Ottoman crusade under Count Amadeus VI of Savoy, supported by Venice and Genoa, was diverted to free the Byzantine emperor. Dobrotitsa/Dobrotici collaborated with the crusaders, and, after the allies conquered several Bulgarian forts on the Black Sea, Ivan Alexander had to allow John free passage and negotiate peace. The Dobrujan ruler's position in this conflict brought him important political gains: he consolidated his position as sovereign ruler, his daughter married one of John V's sons, Michael, and his principality extended its control over Anchialos, Mesembria and other forts lost by Bulgarians during the war.

In 1368, after the death of Demetrius, he was recognised as ruler by Pangalia and other cities on the right bank of the Danube. In 1369, together with Vladislav I of Wallachia, Dobrotitsa/Dobrotici helped Prince Stratsimir regain the throne of Vidin from the Hungarians. Soon after 1369, the Dobrujan ruler also conquered Dristra from the Tsardom of Tarnovo, putting it under the rule of his son, Terter.

At the peak of its power, in 1372, Dobrotitsa/Dobrotici is mentioned under the title of despot, ruling over a large territory, including the fortresses of Varna, Kozeakos (near Obzor) and Emona.

Around 1370, the conflict with the Genoese reignited, Dobrotitsa rallying with Venice in the long war between the two maritime republics. In 1373, he tried to impose his son-in law, Michael, on the throne Trebizond, a Genoese ally, but achieved no success, instead signing a treaty with Alexios III Comnene. In 1376 he tried to gather support for this action from Venice, but, despite the initial agreement, the changing economical interests of the Republic prevented a new attempt. Dobrotitsa also supported John V Palaeologus against his son Andronicus IV Palaeologus, supported by the Genoese. Thus, in 1379, the Dobrujan fleet assisted the Venetians in their naval intervention on Constantinople that led to Andronicus IV's fall. After Venice was forced to make peace with Genoa in 1381, the conflict of Dobrotitsa with the latter escalated again, leading in 1383-1385 to a blockade against the Dobrujan despotate enforced by Pera, a Genoese colony.

In 1386, Dobrotitsa/Dobrotici died and was succeeded by Ivanko/Ioankos, who in the same year made peace with Murad I and in 1387 signed a political and commercial treaty with Genoa, ending a war that had lasted for several decades. Dristra was also recovered by the Tsar of Tarnovo in the same period. Ivanko/Ioankos was killed in 1388 during the expedition of Ottoman Grand Vizier Çandarli Ali Pasha against Tarnovo and Dristra. The expedition brought most of the Dobrujan forts under Turkish rule.

In 1388/1389 Dobruja (Terrae Dobrodicii—as mentioned in a document from 1390) and Dristra (Dârstor) came under the control of Mircea the Elder, ruler of Wallachia, who defeated the Grand Vizier.

Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I conquered the southern part of the territory in 1393, attacking Mircea one year later, but without success. Moreover, in the spring of 1395 Mircea regained the lost Dobrujan territories, with the help of his Hungarian allies. Ottoman recaptured Dobruja in 1397 and ruled it to 1404, although in 1401 Mircea heavily defeated an Ottoman army.

The defeat of Sultan Bayezid I by Tamerlane at Ankara in 1402 opened a period of anarchy in the Ottoman Empire. Mircea took advantage of it to organise a new anti-Ottoman campaign: in 1403, he occupied the Genoese fort of Kilia at the mouths of the Danube, thus being able, in 1404, to impose his authority on Dobruja. In 1416, Mircea supported the revolt against Sultan Mehmed I, led by Sheikh Bedreddin in the area of Deliorman, in Southern Dobruja.[110]

After his death in 1418, his son Mihail I fought against the amplified Ottoman attacks, eventually losing his life in a battle in 1420. That year, the Sultan Mehmed I personally conducted the definitive conquest of Dobruja by the Turks. Wallachia kept only the mouths of the Danube, and not for long time.

In the late 14th century, German traveller Johann Schiltberger described these lands as follows:[111] -

| “ | I was in three regions, and all three were called Bulgaria. ... The third Bulgaria is there, where the Danube flows into the sea. Its capital is called Kaliakra. | ” |

Ottoman rule[edit]

Occupied by the Turks in 1420, Dobruja remained under Ottoman control until the late 19th century. Due to its strategical location on the northern frontier of the Empire, the region was organised as an udj (border province), under an autonomous bey who had the task to organise the local defence and organise raids in the neighbouring Christian countries. Thus, in the first half of 15th century, Dobruja continued to be an unstable region, with plundering expeditions across the Danube by the local Akıncı often being followed by reprisals by Wallachian voyvods. To better secure the border, a permanent Ottoman garrison was installed at Silistra, which rapidly became a powerful fortress, the administrative centre of a sanjak extending over much of the north-eastern Balkans. Its head, a sanjak-bey, was chosen from the upper levels of the Ottoman aristocracy, and had the role to supervise the Turkish vassals to the north, especially the Principality of Moldavia.[112] There is currently no data about the administrative organisation of Dobruja during the early Turkish rule, however at the beginning of 16th century the region was divided into three nahiyas, Silistra, Varna, and Hırsova, joined by the nahiya of Tekfurgölü by the 1560s. As other conquered provinces in the Balkans, Dobruja was not administered centrally, but according to the Timar system, with tracts of land being awarded to Ottoman cavalrymen in return of their military service.[113] Later, during Murad II or Suleiman I, the sanjak of Silistra and surrounding territories became a separate Vilayet.[114]

In 1555, a revolt led by the "false" (düzme) Mustafa, a pretender to the Turkish throne, broke out against Ottoman administration in Rumelia and rapidly spread to Dobruja, but was repressed by the beylerbey of Nigbolu.[115][116] The revolt, described as a djelali by contemporaneous authors, may have also been determined by dissatisfaction of the local Muslim population with the Ottoman feudal system.[117] In 1603 and 1612, the region suffered from the forays of Cossacks, who burnt down Isaķči and plundered Küstendje. The Russian empire occupied Dobruja several times during the Russo-Turkish Wars — in 1771–1774, 1790–1791, 1809–1810, 1829 and 1853. The most violent invasion was that of 1829, which depopulated numerous villages and towns. The Treaty of Adrianople of 1829 ceded the Danube Delta to the Russian Empire. However, Russians were forced to return it to the Ottomans in 1856, after The Crimean War. In 1864 Dobruja was included in the vilayet of Tuna.

During Ottoman rule, groups of Turks, Arabs and Tatars settled in the region, the latter especially between 1512 and 1514. During the reign of Peter I of Russia and Catherine the Great, Lipovans immigrated in the region of the Danube Delta. After the destruction of Zaporozhian Sich in 1775, Cossacks were settled in the area north of Lake Razim by the Turkish authorities (were they founded the Danubian Sich), but they were forced to leave Dobruja in 1828. In the second part of the nineteenth‑century, Ruthenians from the Austrian Empire also settled in the Danube Delta. After the Crimean War, a large number of Tatars were forcibly driven away from Crimea, immigrating to then-Ottoman Dobruja and settling mainly in the Karasu Valley in the centre of the region and around Bābā Dāgh. In 1864, Cherkess fleeing from the Russian invasion of the Caucasus were settled in the wooded region near Bābā Dāgh. Germans from Bessarabia also founded colonies in Dobruja between 1840 and 1892.

In the first half of the 19th century Dobruja also became an important target of seasonal migration. Thousands of labourers from the region of Tırnova and Gorna Oryahovitsa flowed to the region during the harvest season, sometimes under the order of Ottoman authorities. After 1828, the plains of the province were rented as pastures by the shepherds from the area of Kotel, and by 1878 the number of sheep they seasonally brought to Dobruja reached 450,000 head.[118]

According to Bulgarian historian Liubomir Miletich, most Bulgarians living in Dobruja in 1900 were nineteenth century settlers or their descendants.[119][120] In 1850, the scholar Ion Ionescu de la Brad wrote in a study on Dobruja, ordered by the Ottoman government, that Bulgarians came to the region "in the last twenty years or so".[121]

After 1870, the Christian religious organisation of the region was put under the authority of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church by a firman of the Sultan.[122] However, the Greeks and most Romanians in Northern Dobruja remained under the authority of the Greek Archdiocese of Tulča (founded in 1829).[123][124]

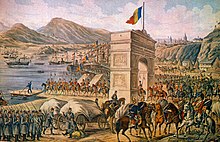

Integration into nation states[edit]

After the 1878 war, Russia received Northern Dobruja, but forced Romania to change southern Bessarabia with it, as Russia wanted a direct access to the Mouths of the Danube. The newly established independent Bulgaria received the southern half of Dobruja in the Treaty of San Stefano, but, after its revision the same year in Treaty of Berlin, it kept a smaller part. In Northern Dobruja, Romanians were the plurality, but the population included a Bulgarian ethnic enclave in the north‑west (around Babadag), as well as an important Muslim community (mostly Turks and Tatars) scattered around the region. At the advice of the French envoy, the Treaty of Berlin awarded a strip of land around the port of Mangalia to Romania as well, since it contained a compact area of ethnic Romanians in its south‑eastern corner. Subsequently, Romania attempted at taking over the town of Silistra, which had been given to Bulgaria due to its large Bulgarian population. A new international commission in 1879 allowed Romania to occupy the fort looking over the city, Arab Tabia, however not the city itself.

At the beginning of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, most of Dobruja's population was composed of Turks and Tatars, but, during the war, a large part of the Muslim population was evacuated to Bulgaria and Turkey.[125] The Romanian administration instituted a special regime in Northern Dobruja, with each of the two newly organised counties being fully subordinated to a prefect designated by the central government. The region was fully integrated into Romania only in 1909, when its inhabitants received the electoral rights guaranteed in the rest of the country since 1866. After 1878, the Romanian government encouraged Romanians from other regions to settle in Northern Dobruja and even accepted the return of some Muslim population displaced by the war.[126] According to Bulgarian historians, after 1878 the Romanian church authorities took control over all local churches, with the exception of two in the towns of Tulcea and Constanţa, which managed to keep their Bulgarian Slavonic liturgy.[127] However, between 1879 and 1900, 15 new Bulgarian churches were built in Northern Dobruja.[128] After 1880, Italians from Friuli and Veneto settled in Greci, Cataloi and Măcin in Northern Dobruja. Most of them worked in the granite quarries in the Măcin Mountains, while some became farmers.[129] The Muslim population continued to leave Dobruja for the Ottoman Empire, with peaks caused by the institution of compulsory conscription in the Romanian Army in 1883 and a severe drought in 1899.

Southern Dobruja had in 1877 a Muslim majority, mostly Turks, as well as a significant Bulgarian population, living in the Danube valley and on the Black Sea coast. A small ethnic Romanian enclave was present around the town of Tutrakan, Gagauz settlements were scattered around Balchik, while the towns of Kavarna and Varna were inhabited by Greeks.[130] After the integration of the region in Bulgaria, the authorities encouraged the settlement of ethnic Bulgarians in the newly acquired territories, mainly on the land left behind by the emigrating Muslims.[131] In early 1900, the imposition of a tithe in kind on arable land, considered abusive by the peasants, provoked discontent among the local population. This evolved into open confrontation between the protesters and government troops on May 19 in the village of Durankulak, clash that left 120 to 150 dead, both peasants and soldiers.[132]

First World War and the Interwar period[edit]

In May 1913, the Great Powers awarded Silistra with a buffer zone of 3 km to Romania, at the Saint Petersburg Conference. In August 1913, after the Romanian army entered Bulgaria unopposed during the Second Balkan War, forcing its surrender, the Treaty of Bucharest awarded Southern Dobruja (Cadrilater) to Romania, despite its feeble Romanian population. The province was put under a regime similar to the one imposed to Northern Dobruja 30 years before, with centrally-appointed prefects holding extended powers. In September 1916, after Romania's entry in World War I on the side of the Entente, an army of the Central Powers under the command of German field marshal August von Mackensen invaded Dobruja. After heavy battles, one of the most significant being the one at Turtucaia, the combined Bulgarian-German-Turkish army conquered all of the province by January 1917, despite strong resistance by Romanian, Russian and Serbian forces.[133] Southern Dobruja reverted immediately to Bulgarian rule, with the rest being put under military administration (German in the centre, Bulgarian in the north).[134] In May 1918, the authorities of occupied Romania agreed to cede Dobruja in a treaty signed in Bucharest: a southern section of Northern Dobruja was awarded to Bulgaria, while the rest was put under the condominium of all Central Powers. However, on 25 September Germany and Turkey agreed to relinquish control over all Dobruja to Bulgaria.[135] The treaty of Bucharest had not been signed by the Romanian king, and was denounced by the government of liberated Romania in October the same year. In November the Allied Powers occupied Dobruja, which was ultimately restored to Romania by the Treaty of Neuilly of November 1919.[136] Despite the proposals to redraw the southern frontier according to the ethnic composition of the region supported by the US, the peace conference, unwilling to take land from an Allied country, decided to reinstate the 1913 border.[137]

Between 1926 and 1938, around 110,000 people were settled in Southern Dobruja, 2/3 of them ethnic Romanians from other regions of Romania, and 1/3 Aromanians from Bulgaria, Macedonia and Greece.[138] The Aromanians were especially nationalist (many of them joining the fascist Iron Guard in the 1930s) and were feared by the local Turks and Bulgarians, who formed the majority of the region. The colonisation caused increased dissatisfaction among the pre-war inhabitants, who had their land expropriated and given to the new settlers, and even had to share their houses with them in some villages. Further problems were caused by the lack of land and the low economical level of the colonists.[139] The general instability, coupled with propaganda by the newly established Turkish Republic, led to intensified emigration among ethnic Turks and Tatars. An agreement was signed in 1936 between Turkey and Romania regulating the emigration process, with priority given to the families from areas considered strategical by Romanian government, such as the border with Bulgaria. By 1938 around 55,000 Muslims had emigrated.[140]

In 1923 the Internal Dobrujan Revolutionary Organisation (IDRO), a Bulgarian nationalist organisation, was established.[141] Active in Southern Dobruja under different forms until 1940, the IDRO detachments fought against the the Romanian administration. With the tacit agreement of the Bulgarian government and the support of locals, it organised armed groups known as komitadjis which crossed the border into Romania and attacked the state authorities, as well as colonists. Thus, while being considered a "terrorist organisation" by the Romanian government, it was regarded in Bulgaria as a liberation movement.[142] In 1925, part of the Bulgarian revolutionary committees formed the Dobrujan Revolutionary Organisation (DRO), which later became subordinated to the Communist Party of Romania.[143] In contrast with the IDRO, which fought for the inclusion of the region in the Bulgarian state, the DRO requested the independence of Dobruja and its inclusion in a projected Federative Republic of the Balkans.[144] DRO distanced itself from the attacks of the komitadjis, preferring to use propaganda and political activism to attain its goals. However this didn't prevent persecution by the Romanian authorities.[145]

Second World War and late 20th century[edit]

With the advent of World War II, Bulgaria regained Southern Dobruja in the September 1940 Axis-sponsored Treaty of Craiova despite Romanian negotiators' insistence that Balchik and other towns should remain in Romania.[146] As part of the treaty, the Romanian inhabitants were forced to leave the regained territory, while the Bulgarian minority in the north was in turn made to leave for Bulgaria in a population exchange.[147] Further change of the population structure was caused by an agreement between Romania and Germany following which around 15,000 Volksdeutsche from Dobruja were resettled in various Nazi-occupied territories during the months of October and November.[148] As Romania joined the Axis in November 1940, Northern Dobruja, a region bordering the Soviet Union, was one of the main zones of concentration of German troops in the country, in preparation for the German-led invasion the Soviet Union.[149][150] In June 1941, during the early phase of the invasion, a Red Army counteroffensive succeeded in occupying the northern Danube Delta, however the swift advance of the Axis troops to the North forced the Soviets to retreat in July.[151] In the following 3 years, as the front moved eastward, the region remained relatively peaceful, however partisan groups, supported by the Soviets, were active in the Delta and the region of Tulcea, sabotaging the Nazi war machine, while Constanţa, Romania's main port, was targeted by several Allied air raids.[152][153][154] Dobruja saw renewed combat in August 1944, when Romania's declaration of war on Germany led to a number of skirmishes between the former allies.[155] After the war, a Soviet garrison was stationed in the province. The main Soviet base, the port of Constanţa, held at times up to a third of the Soviet forces in Romania, and, after the start of the Cold War, preparations were made against an expected amphibious invasion by NATO troops. Soviet troops left Bulgaria by the end of 1947, and Romania by July 1958.[150][156]

During the talks in the aftermath of World War II, the Allies agreed that, unlike other wartime Bulgarian territorial gains, Southern Dobruja should remain under Bulgarian control.[157] In the following years several proposals to modify the border were made, either by awarding Romania a port in Southern Dobruja (1946) or by rectifying the border around Silistra in Bulgaria's favour (1948, 1961-1962). However, the 1940 boundary, confirmed in 1947 by the Paris Peace Treaties, remained unchanged.[158][159]

Soon after the war, with Soviet support, the Communist parties of Bulgaria and Romania came to dominate the political life of their countries, and by the late 40s both states became people's republics. Several isolated anti-communist groups, dominated by Aromanian former members of the Iron Guard, were active in Northern Dobruja in 1948-1949, however they were quickly suppressed by the authorities.[160] The region gradually adapted to the new regime: in Northern Dobruja in 1948 the industrial enterprises in the main urban centres were nationalised, and in 1949 a collectivisation campaign was started, so that in 1957 the region was declared the first fully collectivised in Romania.[161] Similar policies were pursued in Southern Dobruja, where nationalisation started already by 1947, and the collectivisation drive by 1949.[162][156]

The post-war years were also marked by discrimination towards the Muslim population of Dobruja. Place names of Turkish origin were changed to reflect the new majorities, and, beginning with the mid-1950s minority schools were closed, and publications in Turkish language were gradually phased out. The opposition of the ethnic Turks to the new policies of the Bulgarian government led in 1949-1951 to a large scale government-supported emigration, sometimes described as "expulsion" or "deportation". Around 150,000 Turks left Bulgaria, most of them from Southern Dobruja. The emigration greatly enhanced the pace of collectivisation in the region, leading some scholars to assume this was one of the initial aims of the government.[163][162][164] [165]

In 1949 the Romanian authorities, probably under Soviet influence, started a project to shorten the route to the Black Sea by building a canal through central Dobruja. The project was also supposed to help the industrialisation of the region and reduce the effects of drought, which had badly affected the region in 1946-1947.[166] Besides paid labour, special army units, common criminals and political prisoners were used in the project.[167] A number of labour camps were set up on the canal's route, but the number of convicts varied greatly, from 20% in 1950, up to 40% in 1951 and even 60% in 1952 and 1953.[168] Marked by several delays caused by the lack of skilled workforce, the construction was finally stopped in summer 1953, when the government decided the costs were too high. The canal was far from completion, with the irrigation system as the only significant result, but further development was halted for the next 20 years.[169]

As Dobruja had been a largely agrarian region, the new regimes heavily invested in industrialisation. Thus, in Northern Dobruja, in the 50 s and 60 s new industries were brought to the region, such as ironworks and cement manufacturing at Medgidia, a chemical plant at Năvodari, prefabrication, pulp and paper mill at Constanţa. In 1964, Soviet economist E.B. Valev proposed the creation of an "inter-state complex of the Lower Danube" that would have supported a tighter economic integration of an area including Dobruja and adjacent regions in Bulgaria, Romania and Ukraine. The Romanian leadership, dissatisfied with the predominantly agricultural role the country was assigned in the new structure and eager to affirm its independence from the Soviets, strongly criticised the plan, which would not evolve past the proposal stage.[170]

In Bulgaria, collectivisation had transformed Southern Dobruja in the main grain-producing region of the country.To better manage the resources of the region, between the early 1970s and the mid 1980s the former collectives were transformed in large government-controlled agro-industrial complexes.[171] In 1977 a large irrigation project was started near Silistra, which should have provided by 1990 water for about 400,000 ha in Southern Dobruja and the neighbouring regions.[172] The highly mechanized agriculture led to a high level of urbanisation, but also resulted in the depopulation of the countryside.[173]

In February 1985 the Bulgarian authorities implemented in Southern Dobruja the "Revival Process", a nationwide campaign of forced assimilation directed against the Turkish population. The process, involving changing Turkish names into Bulgarian-sounding ones as well as severe restrictions on the freedom of expression, led to numerous acts of civil disobedience among the ethnic Turks of the region.[174] However the accumulated pressure erupted in May 1989, when several protests and hunger strikes were staged in Turkish populated areas over north-eastern Bulgaria.[175] As a reaction, the government opened the border with Turkey and allowed Muslims to emigrate. Around 344,000 ethnic Turks left Bulgaria during summer, an important part of them from the north-east of the country, including Southern Dobruja.[176] 40% percent returned after the fall of the Zhivkov regime resulted in the end of the assimilation campaign and restoration of minority rights.[177]

The sudden economic changes and the reduced state authority in the first years following the fall of the Ceausescu regime in Romania led to some ethnic tension within the region. Among the most publicised were the incidents of October 1990 in Mihail Kogalniceanu, central Dobruja, when several houses of the Roma minority were burned down by local Romanians and Aromanians.[178]

Demographics[edit]

According to official estimates, at the end of 2009, the population of Dobruja was of 1,297,845, three quarters of the inhabitants living in the Romanian part.[179] The population is concentrated on the Danube, the Black Sea coast, and the Danube-Black Sea Canal, the settlements on the latter concentrating over 1/3 of the region's population. While the overall density is around 56 residents per square kilometre, below the average values for both Bulgaria and Romania, the density varies locally. Thus, in the Romanian part, the mean density is 62.3/km², varying from 15/km² in the Danube Delta, to under 40/km² in the interior and over 200/km² in the area of Constanţa and the southern seashore. In the Bulgarian part, the mean value is 43.2/km², slightly higher in the western part.

The urban population of Dobruja constituted 64.5% as of 2010. The proportion varied regionally, from as low as 45% in the Silistra Province to as high as 70% in the Constanţa County. The main cities are the centres of Dobruja's four administrative division (population estimations as of December 2009/January 2010): Constanţa (302,000) and Tulcea (91,000) in Romania, respectively Dobrich (93,000) and Silistra (38,000) in Bulgaria. The four cities account for 40% of the region's population, Constanţa by itself being the residence of 24%. Constanţa is also the only city with an organised metropolitan area, its 450,000 inhabitants making it the second largest metropolitan area in Romania after Bucharest, the capital of the country. There are other 15 cities and towns in the Romanian part and 9 in the Bulgarian part. Most of them are small or medium sized. The towns on the Romanian side are slightly larger. Thus the municipalities of Mangalia and Medgidia have a population of roughly 40,000 each, while Năvodari is home to 36,000. On the other hand, the smallest towns, Alfatar and Glavinitsa, with a population of under 2,000, are located in the Bulgarian part.

The 2009 population estimates constitute a 31,000 drop from the totals recorded by the 2001 Bulgarian census and 2002 Romanian census. The phenomenon was more intense in the south, with the Dobrich and Silistra district each losing around 15,000 inhabitants. In the north the two counties had contrasting evolutions: while the population of the Tulcea County dropped by almost 10,000, the population of Constanţa county increased by 8,500. The population change was caused mainly by negative natural increase. Thus in 2008, except Constanţa, which witnessed an increase of 1.2‰, all the administrative division had a negative change, the most important of -5.9‰ in the district Silistra. The natural movement of the population was also influenced by area of residence, most of Dobruja experiencing a more pronounced decrease in the rural areas. Constanţa county is again an exception, the growth in the rural areas being of 2.2‰, compared to 0.7‰ in the urban areas.

From the second part of the 19th centuries to the late 1980s Dobrudja experienced a continual population growth. Several migration waves affected the number and structure of the population. When not outright forced, the population movements were encouraged by the governments ruling over the province, and where generally based on ethnic criteria. The first reliable data about Dobruja's population is a 1850 study ordered by the Ottoman government, which recorded xxxx families (the region of Silistra excluded). The author, Romanian agronomist Ion Ionescu de la Brad, noted however that several settlements had been destroyed during the Russo-Turkish war of 1829. During the late 19th century several estimates were made by scholars: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX. By the beginning of World War I, the pro-immigration policies of the Bulgarian and Romanian nation states had brought the population to around 660,000 (cca 60% in Northern Dobruja). In 1930, the first and only census to unitarilyy record the population of Dobruja, counted 972,000 inhabitants. After World War II growth slowed, and most of the immigration was economically motivated. By 1992, the population, as recorded by the Bulgarian and Romanian national censuses, increased to 1,413,000 (72% in Northern Dobruja). Since the early 90s reduced fertility, population ageing, deteriorating economic conditions and liberalized emigration dramatically changed the trend, causing a significant decrease, more important in Southern Dobruja (a 17% drop between 1992 and 2009).

Northern Dobruja[edit]

| Ethnicity | 1880[180] | 1899[181] | 1913[182] | 19301[183] | 1956[184] | 1966[184] | 1977[184] | 1992[184] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 139,671 | 258,242 | 380,430 | 437,131 | 593,659 | 702,461 | 863,348 | 1,019,766 |

| Romanian | 43,671 (31%) | 118,919 (46%) | 216,425 (56.8%) | 282,844 (64.7%) | 514,331 (86.6%) | 622,996 (88.7%) | 784,934 (90.9%) | 926,608 (90.8%) |

| Bulgarian | 24,915 (17%) | 38,439 (14%) | 51,149 (13.4%) | 42,070 (9.6%) | 749 (0.13%) | 524 (0.07%) | 415 (0.05%) | 311 (0.03%) |

| Turkish | 18,624 (13%) | 12,146 (4%) | 20,092 (5.3%) | 21,748 (5%) | 11,994 (2%) | 16,209 (2.3%) | 21,666 (2.5%) | 27,685 (2.7%) |

| Tatar | 29,476 (21%) | 28,670 (11%) | 21,350 (5.6%) | 15,546 (3.6%) | 20,239 (3.4%) | 21,939 (3.1%) | 22,875 (2.65%) | 24,185 (2.4%) |

| Lipovan Russian | 8,250 (6%) | 12,801 (5%) | 35,859 (9.4%) | 26,210 (6%)² | 29,944 (5%) | 30,509 (4.35%) | 24,098 (2.8%) | 26,154 (2.6%) |

| Ruthenian (Ukrainian from 1956) |

455 (0.3%) | 13,680 (5%) | 33 (0.01%) | 7,025 (1.18%) | 5,154 (0.73%) | 2,639 (0.3%) | 4,101 (0.4%) | |

| Dobrujan Germans | 2,461 (1.7%) | 8,566 (3%) | 7,697 (2%) | 12,023 (2.75%) | 735 (0.12%) | 599 (0.09%) | 648 (0.08%) | 677 (0.07%) |

| Greek | 4,015 (2.8%) | 8,445 (3%) | 9,999 (2.6%) | 7,743 (1.8%) | 1,399 (0.24%) | 908 (0.13%) | 635 (0.07%) | 1,230 (0.12%) |

| Gypsies | 702 (0.5%) | 2,252 (0.87%) | 3,263 (0.9%) | 3,831 (0.88%) | 1,176 (0.2%) | 378 (0.05%) | 2,565 (0.3%) | 5,983 (0.59%) |

Southern Dobruja[edit]

| Ethnicity | 1910 | 19301[183] |

|---|---|---|

| All | 282,007 | 378,344 |

| Bulgarian | 134,355 (47.6%) | 143,209 (37.9%) |

| Romanian | 6,348 (2.3%) | 77,728 (20.5%) |

| Turkish | 106,568 (37.8%) | 129,025 (34.1%) |

| Tatar | 11,718 (4.2%) | 6,546 (1.7%) |

| Gypsies | 12,192 (4.3%) | 7,615 (2%) |

- 1According to the 1926–1938 Romanian administrative division

- 2Only Russians. (Russians and Lipovans counted separately)

The entire Dobruja has an area of 23,100 km² and a population of rather more than 1.3 million, of which just over two-thirds of the former and nearly three-quarters of the latter lie in the Romanian part.

| Ethnicity | Dobruja | Romanian Dobruja[185] | Bulgarian Dobruja[186] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| All | 1,328,860 | 100.00% | 971,643 | 100.00% | 357,217 | 100.00% |

| Romanian | 884,745 | 66.58% | 883,620 | 90.94% | 5911 | 0.17%1 |

| Bulgarian | 248,517 | 18.70% | 135 | 0.01% | 248,382 | 69.53% |

| Turkish | 104,572 | 7.87% | 27,580 | 2.84% | 76,992 | 21.55% |

| Tatar | 23,409 | 1.76% | 23,409 | 2.41% | 4,515 | 1.26% |

| Roma | 33,422 | 2.52% | 8,295 | 0.85% | 25,127 | 7.03% |

| Russian | 22,495 | 1.69% | 21,623 | 2.23% | 872 | 0.24% |

| Ukrainian | 1,571 | 0.12% | 1,465 | 0.15% | 106 | 0.03% |

| Greek | 2,326 | 0.18% | 2,270 | 0.23% | 56 | 0.02% |

- 1 Including persons counted as Vlachs in Bulgarian 2001 Census

Major cities are Constanţa, Tulcea, Medgidia and Mangalia in Romania, and Dobrich and Silistra in Bulgaria.

Economy and transportation[edit]

The favourable climate, soil conditions and flat topography made the region of Dobruja an important agricultural region. Since Antiquity, the province was an important provider of grain and animal products to the Mediterranean region. Its strategic position, near the Mouths of the Danube and on the way linking the Eastern Mediterranean world with the East European steppes, favoured commerce, attracting numerous foreign merchants. Manufacturing had generally a low importance, and only in the 20th century industry become an important part of the region's economy. The 20th century also brought an increased economic differentiation inside the region: while the north and the south maintained their primarily agricultural role, the industrial and tertiary sectors became predominant in the Carasu Valley and the Black Sea shore around the city of Constanţa.

Agriculture[edit]

Until the 19th century, most of Dobruja was covered by steppe and forest steppe. The large pastures and Ottoman property system created favourable conditions for the development of extensive animal husbandry, which was the main occupation in the region well into the 20th century. The grazing fields also attracted transhumant shepherd populations from the Carpathians and the Balkan Mountains. A part of them settled in Dobruja in the late 18th and 19th century, helping repopulate the region after several Russo-Turkish Wars left many of its settlements deserted.[187]

After Dobruja was divided among nation states (Bulgaria and Romania) in 1878, the new states began programs to bring the pastures into agricultural use. The move was motivated not only by economic reasons, but also by the desire to attract settlers of the titular ethnic groups to the region, thus changing the ethnic make-up of the province, dominated until the 19th century by Muslim populations. The chaotic nature of the land property system under the Ottoman rule allowed the new authorities to expropriate ample territories and open them to settlement. These policies helped create larger agricultural plots, favouring more intensive forms of land cultivation.[188][189]

With the establishment of the socialist forms of property in the late 1940s, the merging of the small plots allowed for intensive agriculture. Large agricultural improvement projects were implemented, including terracing, land reclamation, mechanisation and use of pesticides and artificial fertilisers. Several agricultural research stations were created to develop new cultivars and breeds: for cereals and fruits at Valu lui Traian, for sheep breeding at Palas, for grapevine at Murfatlar, for potatoes in Tulcea in Romania, and for apricots at Silistra and wheat and sunflower at General Toshevo in Bulgaria. The lack of major rivers and the low water table, coupled with low precipitation, cause frequent droughts which severely affect the agricultural production. To alleviate the problem, the authorities developed extensive irrigation systems in the second part of the 20th century.[190] Thus, in Northern Dobruja, around 597,000 hectares (64.5% of the agricultural lands) were irrigated by the late 1980s. The most important systems were Carasu, which used water from the Danube-Black Sea Canal, and Sinoe, which used water from the Razim-Sinoe lagoon complex.[191] In 1977 a large irrigation project was also started near Silistra, in Southern Dobruja, which by 1990 should have provided irrigation for about 400,000 ha in Southern Dobruja and the neighbouring regions.[192] The development of the systems was facilitated by communist forms of property, which allowed for centralised management of large agricultural areas. With the fall of the regimes in 1989, the land was divided in small plots, and the irrigation almost ceased. Most of the complex hydrographical networks felt in disrepair due to lack of funds, and a part were outright destroyed.[193][194] Another measure for the prevention of drought effects was the planting of forest belts. The project started already before World War II, however most of the belts in the Romanian part of Dobruja were cut down in the 1960s at the time of the construction of the irrigation system.[195] In the 1970s and 1980s reclamation projects were started in the Danube Delta. Thus 53,000 ha were reclaimed for agricultural use, 45,000 for fish farming, and 4,500 ha for foresting. After 1990, due to concerns about the effects of agricultural activities on the biodiversity of the Delta, part of the reclaimed land was restored to its natural state (16,000 ha of agricultural land and 12,500 ha of fish farms).[196]

Nowadays, most of Dobruja's territory is used for agriculture. In Northern Dobruja, agricultural terrains constitute 60% of the province's area, the rest being taken by forests, swamps and water surfaces. Of the agricultural lands, 80% is arable land, and only 13.6% were preserved as pastures. Smaller areas are reserved for orchards and vineyards.[197] High proportions are also recorded in Southern Dobruja. Thus, in the district of Dobrich, 80% of the territory is agricultural terrain, of which around 90% arable land and 8% meadows and orchards. In the district Silista agricultural territory represents 70.4% of the area, arable land occupying by itself 60%, while vineyards and orchards 3.2%.The productivity of agriculture has steadily decreased since the 1989 regime change. Factors included the restoration of private property, slow reforms, obsolete machinery, the loss of foreign markets (Comecon) and the lack of a credit system for farmers.[198]

Southern Dobruja is the largest grain-producing region of Bulgaria, often referred as "Bulgaria’s breadbasket".

In 2006, around 370,000 hectares were cultivated in the district of Dobrich, of which 6,708 ha irrigable. Not all irrigation equipment is however fully exploited. The most important crops were wheat(over one third of the arable land), sunflower and corn. Despite the risks of monoculture, the district continues to be one of the most important agricultural producers in Bulgaria, providing more than 15% of the Bulgarian wheat, as well as 15% of the national corn production, and 15% to 18% of the sunflower production, all on only 4.3% of the national territory. The latter has especially high productivity due to climatic conditions and superior cultivars, making it an important export item. Other traditional crops include beans, soya beans, peas and lentil, nowadays with a reduced production. Cultivation of industrial plants such as tobacco or sugar beet is limited due to reduced demand from the industry. Flax, once widely cultivated in the littoral area, has disappeared once most processing plants in Bulgaria were closed in the 1990s. However, since the 1990s the surface cultivated with barley has constantly grown. Various vegetables are grown, especially in the region of Shabla, Kavarna and Dobrich, however the production does not satisfy the local demand. Animal husbandry is greatly reduced nowadays. At its heights, in the 1980s livestock was bred in several large complexes under a central administration. The annual production amounted to 285,000 to 300,000 pigs, 9,000 calves, and 22,000 hoggets. A smaller number was produced in private farms. After 1989 the reduced market demand, competition from low-quality imports and low purchase prices greatly reduced the capacity, and most complexes have disappeared. Thus the livestock population was composed in 2001 of 18,000 head of cattle, 24,000 swine, 73,000 head of sheep, and 452,000 poultry.

In the early 2000s, in the district of Silista cultivated area covered 170,800 ha, about half of them being in private ownership. Irrigable area constituted 4,326 ha, however due to lack of repair or intentional damage, only 3,485 ha were effectively irrigated. The structure of the crops is similar to the one in the Dobrich district: wheat (26.2% of the cultivated area), sunflower (17.6%) and corn (16.0%) make up most of the fields. Another important traditional crop is tobacco, was cultivated in 2004 on 1,900 ha, the most important varieties being Burley and Oriental. Fruits are cultivated on around 3,200 ha. Apricots, a traditional and famed product of the region, occupy 90% of this area, the orchards being concentrated in the municipalities of Dulovo, Glavinitsa and Silistra. However, most of the orchards have ageing problems, and economical conditions prevent young plantations. The rest of the orchards are used for growing peaches, wild cherries and sour cherries. Vineyards, primarily wine-producing varieties, occupy around 2,500 ha, mostly in the municipality of Silistra, and less in Sitovo and Tutrakan. Legumes production has significantly decreased after 1989. Following a massive decrease following the regime change, animal husbandry has shown slight improvement beginning with the 2000s. However local demand still exceeds the supply. There are around 16,000 head of cattle, however most are grown in small farms, with almost no industrialisation. The situation is similar for sheep and goats (66,000 respectively 26,500 in 2004). The situation is better with swine (48,000 in 2004), as the production, in medium farms with modern equipment, is more oriented toward the market. Cuniculture is well developed, with 15,000 domestic rabbits being recorded in 2004, as is apiculture, a traditional activity in the region, with 30,000 families of honeybees being recorded in the same year with a production of 500 tones of honey. On the other hand, poultry farming is on a downward trend.

As of 2000, there are around 700,000 ha of cultivated land in Northern Dobruja. In the early 1980s, the region provided for 10% of the Romanian agricultural production.[199] Most of the agricultural land is nowadays privately owned. The predominant cultures are cereals, with 60% of the arable land being cultivated with wheat, rye and corn.[200] Sunflower is cultivated, as of 2008, on 12% of the arable land,[201] Northern Dobruja providing 16% of the Romanian production in 1980. Linseed for oil is cultivated on limited areas in the southern part of Northern Dobruja. Among bean-bearing legumes, significant cultures are the common bean and soya, with an important centre at Topalu.[202] Other legumes are grown intensively in the southern part of the littoral area, the production being destined to the summer resorts and the city of Constanta.[203] The region of Isaccea was a traditional tobacco growing region, however cultivation had ceased by the 2000s.

Dobruja is also an important wine-producing region, vine-growing being favoured by the dry climate and calcareous soil. Only the Constanţa County had over 16,000 ha cultivated with grapevine as of 1980. The largest vineyards are located in the central area, along the Carasu Valley. The vineyards, established in the early 20th century and collectively known as Murfatlar, produces several varieties of wine, including Chardonnays, Muscat Ottonel and Fetească. The wines are renowned around the world, and have received several international awards. Another important vineyard is Sarica-Niculiţel, in the north of the region, while lesser vineyards are located at Ostrov, Turcoaia, Măcin and Tulcea.[204]

The warmer climate allows for the production of peaches, apricots, cherries and sour cherries, fruits not cultivated intensively in other parts of Romania. Orchards are found on the Carasu Valley (apricots at Nazarcea, peaches at Medgidia) and in the south of the province, providing fresh fruits to the seashore region, as well as in the Tulcea Hills and the Isaccea region in the north.[205] The northern region is also known for its quince and pears orchards near Isaccea. The region of Ostrov, in the south-west, is an important producer of table grapes (Afuz-Ali variety).[206] Kiwi fruit was successfully acclimatised in the same region, but the culture is currently only experimental.[207]