Einstein–Oppenheimer relationship

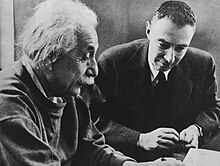

Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer were twentieth century physicists who made pioneering contributions to physics. From 1947 to 1955 they had been colleagues at the Institute for Advanced Study. Belonging to different generations, Einstein and Oppenheimer became representative figures for the relationship between "science and power", as well as for "contemplation and utility" in science.[a]

Overview[edit]

[Before World War II] Oppenheimer’s reputation and influence were centered around the small and close circle of physicists. As the wartime director of Los Alamos Laboratory, he was bound to receive important public attention, but there were other directors of great laboratories, and other physicists, who shared equal esteem but did not become objects of such general interest. Oppenheimer after Einstein emerged as the great charismatic figure of the scientific world.

In 1919, after the successful verification of the phenomenon of light from faraway stars bending near the sun, as predicted earlier by Einstein's theory of gravity became an observable fact, Albert Einstein was acclaimed as “the most revolutionary innovator in physics” since Isaac Newton.[2] J. Robert Oppenheimer, called the "boy-wonder" of the American physics community in the 1930s, became a popular figure from 1945 onwards after overseeing the first ever successful test of nuclear weapons.[3]

Both Einstein and Oppenheimer were born into nonobservant Jewish families.[4] Belonging to different generations, Einstein (1879–1955) and Oppenheimer (1904–1967), with the full development of quantum mechanics by 1925 marking a delineation, represented the shifted approach in being either a theoretical physicist or an experimental physicist since the mid-1920s when being both became rare due to the division of labor.[5]

Einstein and Oppenheimer, both of whom incorporated different modes of approach for their achievements, became emblematic for the relationship between "science and power", as well as for "contemplation and utility" in science.[a] Einstein was markedly individualistic in his approach to physics. He had only few students and was disinterested, if not adversarial in his relation with formal institutions and politics.[7] Oppenheimer was more collaborative and embraced collective scientific work. He had been a better successful teacher and more immersed in political and institutional realms.[7] Oppenheimer emerged as a powerful political 'insider', a role that Einstein never embraced but wondered why Oppenheimer desired such power.[8] Despite their different stances, both Oppenheimer and Einstein were regarded "deeply suspicious" by the authorities, specifically by J. Edgar Hoover.[8]

With the advent of modern physics in the twentieth century changing the world radically, both Einstein and Oppenheimer grappled with metaphysics that can provide an ethical framework for human actions.[9] Einstein turned to the philosophical works of Spinoza and Schopenhauer, along with an attachment to the European enlightenment heritage. Oppenheimer became engrossed in the eastern philosophy, with particular interest in the Bhagavad Gita, and an affinity with the American philosophical tradition of pragmatism.[9]

Association with each other[edit]

Oppenheimer met Einstein for the first time in January 1932 when the latter visited Caltech as part of his round-the-world trip during 1931-32.[10]

In 1939, Einstein published a paper that argued against the existence of Black holes. Einstein used his own general theory of relativity to arrive at this conclusion.[11] A few months after Einstein rejected the existence of Black holes, Oppenheimer and his student Hartland Snyder published a paper that revealed, for the first time, using Einstein's general theory of relativity, how Black holes would form.[11] Though Oppenheimer and Einstein later met, there's no record of them having discussed Black holes.[11]

When in 1939 the general public became aware of the Einstein–Szilard letter that urged the US government to initiate the Manhattan project for the development of nuclear weapons, Einstein was credited for foreseeing the destructive power of the atom with his mass–energy equivalence formula.[12] Einstein played an active role in the development of US nuclear weapons by being an advisor to the research that ensued, this was in contrast to the common belief that his role was limited to only signing a letter.[7] During this time, the public linked Einstein with Oppenheimer, who then happened to be the scientific director of the Manhattan project.[12] In 1945, when Oppenheimer and Pauli were being considered for a professorial position at an institute, Einstein and Hermann Weyl wrote a letter that recommended Pauli over Oppenheimer.[13]

After the end of World War II, both Einstein and Oppenheimer lived and worked in Princeton at the Institute for Advanced Study, Einstein became a professor there while Oppenheimer its director and a professor of physics from 1947 to 1966.[11][14][15] They had their offices down the hall from each other.[16] Einstein and Oppenheimer became colleagues and conversed with each other occasionally.[14][11] They saw each other socially, with Einstein once attending dinner at the Oppenheimers in 1948.[13] At the Institute, Oppenheimer considered general relativity to be an area of physics that wouldn't be of much benefit to the efforts of physicists, partly due to lack of observational data and due to conceptual and technical difficulties.[17] He actively prohibited people from taking up these problems at the institute. Furthermore he forbade Institute members from having contacts with Einstein.[17] For one of Einstein's birthday, Oppenheimer gifted him a new FM radio and had an antenna installed on his house so that he may listen to New York Philharmonic concerts from Manhattan about 50 miles away from Princeton.[13] Oppenheimer did not provide an article to the July 1949 issue of Reviews of Modern Physics, which was dedicated to the seventieth birthday of Einstein.[17]

In October 1954, when an honorary doctorate was to be conferred to Einstein at Princeton, Oppenheimer made himself unavailable at the last moment despite being "begged" to attend the event. He informed the convocation committee that he had to be out of town on the day of convocation.[17] Earlier in May 1954, when the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee decided to honour Einstein on his seventy-fifth birthday, the American Committee for Cultural Freedom, concerned about the Communist ties of the honouring committee, requested Oppenheimer to stop Einstein from attending the event lest it may cause people to associate Judaism with Communism, and think of scientists as naive about politics. Oppenheimer who was then busy with his security clearance hearings persuaded Einstein to dissociate with the honouring committee.[18]

Views about each other[edit]

In January 1935, Oppenheimer visited Princeton University as a visiting faculty member on an invitation.[10] After staying there and interacting with Einstein, Oppenheimer wrote to his brother Frank in a letter thus, "Princeton is a madhouse: its solipsistic luminaries shining in separate & helpless desolation. Einstein is completely cuckoo. ... I could be of absolutely no use at such a place, but it took a lot of conversation & arm waving to get Weyl to take a no”.[10] Oppenheimer's initial harsh assessment was attributed to the fact that he found Einstein highly skeptical about the quantum field theory. Einstein never accepted the quantum theory, in 1945 he said: "The quantum theory is without a doubt a useful theory, but it does not reach to the bottom of things. I never believed that it constitutes the true conception of nature".[10] Oppenheimer also noted that Einstein became very much a loner in his working style.[10]

After the death of Einstein in April 1955, in a public eulogy Oppenheimer wrote that "physicists lost their greatest colleague". He noted that of all the great accomplishments in Physics, the theory of general relativity is the work of one man, and it would have remained undiscovered for a long time had it not been for the work of Einstein.[19] He ascertained that public image of Einstein as a simple and kindhearted man “with warm humor,... wholly without pretense” was indeed right, and remembered what Einstein once said to him before his death, "You know, when it once has been given to a man to do something sensible, afterwards life is a little strange." Oppenheimer wrote that it was given to Einstein to do "something reasonable".[19][20] He stated that general theory of relativity is "perhaps the single greatest theoretical synthesis in the whole of science".[21] Oppenheimer wrote that more than anything the one special quality that made Einstein unique was “his faith that there exists in the natural world an order and a harmony and that this may be apprehended by the mind of man”, and that Einstein had given not just an evidence of that faith, but also its heritage.[21]

Oppenheimer was less graceful about Einstein in private. He said Einstein had no interest or understood modern physics, and wasted his time in trying to unify gravity and electromagnetism.[22] Oppenheimer complained that Einstein did not leave any papers to the institute in his will despite the support he received from the institute for twenty-five years, all the papers went to Israel.[22] Oppenheimer stated that Einstein's methods in his final years had in "a certain sense failed him".[23] Einstein in his last twenty-five years of life focussed solely on working out the unified field theory without considering its reliability nor questioning his own approach. This led to him loose connections with the wider physics community.[24] Einstein's urge to find unity had been constant throughout his life. In 1900, while still a student at ETH, he wrote in a letter to his friend Marcel Grossmann that, "It is a glorious feeling to recognize the unity of a complex of phenomena, which appear to direct sense perceptions as quite distinct things."[25] In 1932, when questioned about his goal of work, Einstein replied, "The real goal of my research has always been the simplification and unification of the system of theoretical physics. I attained this goal satisfactorily for macroscopic phenomena, but not for the phenomena of quanta and atomic structure." And added, "I believe that despite considerable success, the modern quantum theory is still far from a satisfactory solution of the latter group of problems."[25] Einstein was never convinced with the quantum field theory, which Oppenheimer advocated.[10][15] Oppenheimer noted that Einstein tried in vain to prove that there are inconsistencies in the quantum theory, but there were none.[23][26] In the 1960s Oppenheimer became skeptical about Einstein's general theory of relativity as the correct theory of gravitation. He thought Brans–Dicke theory is a better theory.[27]

In December 1965, Oppenheimer visited Paris on an invitation from UNESCO to speak at the tenth anniversary of Einstein's death. He spoke on the first day of the commemoration as he had known Einstein for more than thirty years and at the Institute of advanced study they "were close colleagues and something of friends". Oppenheimer made his critical views of Einstein public there.[28] He also praised Einstein for his stand against violence and described his attitude towards humanity by the Sanskrit word Ahimsa.[29] The speech received considerable media attention, New York Times reported the story headlined “Oppenheimer View of Einstein Warm But Not Uncritical”.[30] After the speech, in an interview with the French magazine L'Express, Oppenheimer said, "During all the end of his life, Einstein did no good. He worked all alone with an assistant who was there to correct his calculations... He turned his back on experiments, he even tried to rid himself of the facts that he himself had contributed to establish ... He wanted to realize the unity of knowledge. At all cost. In our days, this is impossible." But nevertheless Oppenheimer said he was "convinced that still today, as in Einstein’s time, a solitary researcher can effect a startling discovery. He will only need more strength of character". The interviewer concluded asking Oppenheimer if he had any longing or nostalgia, to which he replied "Of course, I would have liked to be the young Einstein. This goes without saying."[31]

Einstein appreciated Oppenheimer for his role in the drafting and advocacy of the Acheson–Lilienthal Report, and for his subsequent work to contain the Nuclear arms race between the United States and Soviet union.[13] At the Institute for advanced study, Einstein acquired profound respect for Oppenheimer on his administration skills, and described him as an “unusually capable man of many sided education”.[13]

In popular culture[edit]

A semifictional account of the relationship between Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer was portrayed in the feature film Oppenheimer directed by Christopher Nolan.[15][16]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Where Einstein emphasized the contemplative aspects of modern science as ‘knowledge for its own sake’, Oppenheimer embodied a practical drive (p. 295). Interestingly, in his assessment of Einstein, Oppenheimer rejected the popular notion that Einstein’s scientific work was otherworldly and devoid of utility. Oppenheimer ‘remarked that one of the most spectacular projects of contemporary physics was to tap the sources of the sun’s energy a project made possible by Einstein’s early work on relativity’ (p. 269). Schweber’s study of Einstein and Oppenheimer therefore is, in part, a reflection on the relationship between contemplation and utility in science. It is also a reflection on the relationship between science and power contrasting Einstein’s persona as itinerant outsider, with Oppenheimer’s development into an expert for the state.[6]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Schweber 2009, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Schweber 2006, p. 513.

- ^ Schweber 2006, p. 514.

- ^ Schweber 2009, p. 283.

- ^ Schweber 2006, pp. 514, 516.

- ^ Thorpe 2011, p. 559.

- ^ a b c Beyler 2009.

- ^ a b Thorpe 2011, p. 560.

- ^ a b Thorpe 2011, pp. 560–561.

- ^ a b c d e f Schweber 2006, p. 528.

- ^ a b c d e Bernstein 2007.

- ^ a b Halpern 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Schweber 2009, p. 271.

- ^ a b Schweber 2006, p. 531.

- ^ a b c Busis 2023.

- ^ a b Cava 2023.

- ^ a b c d Schweber 2006, pp. 532.

- ^ Schweber 2006, pp. 533.

- ^ a b Oppenheimer 1956.

- ^ Schweber 2006, p. 534, 538.

- ^ a b Schweber 2006, pp. 534.

- ^ a b Schweber 2006, p. 535.

- ^ a b Sherwin 1979.

- ^ Schweber 2006, p. 516.

- ^ a b Schweber 2009, p. 300.

- ^ Schweber 2009, p. 279.

- ^ Schweber 2006, p. 523.

- ^ Schweber 2006, pp. 535–536.

- ^ Schweber 2006, p. 538.

- ^ Schweber 2009, p. 281.

- ^ Schweber 2009, p. 282.

Sources[edit]

- Schweber, Silvan S. (2009). Einstein and Oppenheimer: The Meaning of Genius. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674043350.

- Sherwin, Martin (1979). "Oppenheimer on Einstein". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 35 (3): 36–39. doi:10.1080/00963402.1979.11458597.

- Thorpe, Charles (2011). "Einstein and Oppenheimer". Annals of Science. 68 (4): 558–561. doi:10.1080/00033790903243332. S2CID 144897605.

- Beyler, Richard H. (2009). "Review of Einstein and Oppenheimer: The Meaning of Genius, by S. S. Schweber". Technology and Culture. 50 (3): 722–23. doi:10.1353/tech.0.0301. JSTOR 40345767. S2CID 122580181.

- Oppenheimer, J. Robert (1956). "Einstein". Reviews of Modern Physics. 28 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.28.1.

- Schweber, Silvan S. (2006). "Einstein and Oppenheimer: Interactions and Intersections". Science in Context. 19 (4). United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press: 513–559. doi:10.1017/S0269889706001050. S2CID 145807656.

- Halpern, Paul (2019). "Albert Einstein, celebrity physicist". Physics Today. 72 (4). American Institute of Physics: 38–45. doi:10.1063/PT.3.4183. S2CID 187603798.

- Bernstein, Jeremy (2007). "The Reluctant Father of Black Holes". Scientific American. 17: 4–11. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0407-4sp. Archived from the original on January 15, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- Busis, Hillary (July 25, 2023). "Einstein and Oppenheimer's real relationship was cordial and complicated". gq-magazine.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 30, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- Cava, Marco della (July 22, 2023). "Fact-checking 'Oppenheimer': Was Albert Einstein really a friend? What's true, what isn't". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024.