Diversity (politics)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Diversity within groups is a key concept in sociology and political science that refers to the degree of difference along socially significant identifying features among the members of a purposefully defined group, such as any group differences in racial or ethnic classifications, age, gender, religion, philosophy, politics, physical abilities, socioeconomic background, sexual orientation, gender identity, intelligence, physical health, mental health, genetic attributes, personality, behavior, or attractiveness.[1]

When measuring human diversity, a diversity index exemplifies the likelihood that two randomly selected residents have different ethnicities. If all residents are of the same ethnic group it is zero by definition. If half are from one group and half from another, it is 50. The diversity index does not take into account the willingness of individuals to cooperate with those of other ethnicities.[2]

International human rights[edit]

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities affirms to "respect difference and acceptance of persons with disabilities as human diversity and humanity" for protection of human rights of persons with disabilities.[3]

Ideology[edit]

Political creeds which support the idea that diversity is valuable and desirable hold that recognizing and promoting these [which?] diverse cultures may aid communication between people of different backgrounds and lifestyles, leading to greater knowledge, understanding, and peaceful coexistence.[citation needed] For example, "Respect for Diversity" is one of the six principles of the Global Greens Charter, a manifesto subscribed to by green parties from all over the world. In contrast to diversity, some political creeds promote cultural assimilation as the process to lead to these ends.

Use in American academy[edit]

This use of diversity in this sense [which?] also extends to American academy, where in an attempt to create a "diverse student body" typically supports the recruitment of students from historically excluded populations, such as students of African American or Latino background as well as women in such historically underrepresented fields as the sciences.[citation needed]

Business and workplace[edit]

Corporations make commitments to diversity in their personnel both for reasons of brand halo and competitive advantage, but progress is slow.[4] [clarification needed]

Gender in Politics[edit]

Historically, women have been underrepresented in politics compared to men. Women's rights movements, such as feminism, have addressed the marginalization of women in politics.[5] Despite traditional doubts concerning female leadership, women have governed for at least a year in about one in four countries since 1960. [6]

United Kingdom[edit]

Among the 61 Prime Ministers of the U.K. (Kingdom of Great Britain until 1801) there have been 3 women: Margaret Thatcher (1979–1990), Theresa May (2016–2019), Liz Truss (2022).

United States[edit]

There has been an increase in women taking on leadership roles in both the public and private sectors of many countries, including the United States. [7] However, there is still a "political gap" between men and women. Women are less likely than similarly situated men to consider running for office; less likely to run for office; less like to believe they are qualified to seek office; less likely to receive encouragement to run for office; and more likely to perceive a competitive, biased electoral environment. [8]

White House Executive Offices[edit]

Administrations since Franklin Roosevelt's have placed aides and units charged with specific outreach to interests and constituencies in the "West Wing". [9] However, specific positions and units devoted to women did not appear in the White House Offices until the late 1960s under John F. Kennedy's administration. Kennedy appointed Esther Peterson to be assistant secretary of labor and direct the department’s Women’s Bureau. Peterson worked to pass the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and was one of many to urge Kennedy to create the President’s Commission on the Status of Women. After Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson named her to an additional post for consumer affairs. Johnson’s administration's efforts to boost the representation of women revolved around highlighting consumer issues. [10]

President Richard Nixon did not appoint a woman assistant to the President’s Task Force on Women’s Rights and Responsibilities, Nixon appointed Anne Armstrong to the most senior WHO position: counselor to the president with cabinet rank. However, she was overwhelmed along with her small staff of two people and did not get to focus on representing women. Her work didn’t particularly concern women’s rights, however, scholars agree that she was an important step for the White House to have female representation in the offices, she “brought a new perspective to White House deliberations ensuring that names of women were included as candidates for vacant positions”. Armstrong was one of the first women to have direct access to the president as a White House staffer. [9]

President Bill Clinton sought to build support among women more generally, especially following the 1990s healthcare debacle and the election of 1994, which the Democratic Party faced substantial losses. In 1995, the administration created the White House Office for Women’s Initiatives and Outreach (OWIO). This was created to “better serve President Clinton’s constituents”. OWIO hosted many events and roundtable discussions and linked with many external organizations. The author states that these actions are symbolic representations. It was initially successful at connecting with women’s groups and providing their findings to the President. However, in 1996, OWIO’s activities substantially declined with the 1996 election and staff changes. [9]

Mayors in the US[edit]

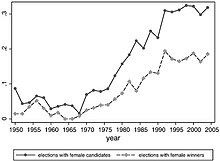

Local governments in the United States certainly have experienced an upsurge in female participation in politics. The graph depicts the increase in female participation in mayoral elections from 1950 to 2005 (see below). [11] The graph utilizes a regression discontinuity design to mitigate the potential influence of city characteristics on the candidacy of women. The findings reveal that the gender of the mayor has no discernible effect on various policy outcomes, such as the scale of local government, the allocation of municipal resources, or crime rates. These conclusions hold true both in the short term and over extended periods. Despite this lack of policy divergence, female mayors exhibit heightened political efficacy, indicated by a notable increase in their incumbent advantage compared to male counterparts. It's worth noting that electing a female mayor didn't have a big impact on whether other women could win elections later on. Having a female mayor did not make it easier for other women to get elected as mayors or in local congressional races. [7]

Latin America[edit]

Associations between women and integrity appear in Latin America where 32.6 percent of citizens in 2012 said that men are more corrupt as politicians while just 4 percent said women are more corrupt. [6] Explanations for this “pro-women” stereotype relate to women’s historical status as outsiders as well as their traditional identities as mothers.

Michelle Bachelet's 2006 election marked the beginning of a string of presidenta victories in Latin America. She set records for presidential popularity in Chile during her first term, and won reelection in one of the most lopsided contests in the country’s history. However, a scandal (Caso Caval) erupted in February of 2015, where her daughter-in-law and son, Sebastián Dávalos, were accused of tax fraud. Dávalos was the Social-Cultural Director, a position traditionally reserved for first ladies. He resigned ten days later. [10]

Although Bachelet was never directly involved in the scandal, her approval ratings fell from 42 percent in the last quarter of 2014 to 36 percent in the first quarter of 2015 (the period immediately after Caso Caval erupted), 31 percent in the second quarter, and 27 percent in the third quarter. These numbers never fully bounced back, hitting 38 percent by February 2018. [6]

Race in politics[edit]

United Kingdom[edit]

Rishi Sunak (since 2022) is the first non-white Prime Minister of the U.K.

United States[edit]

In American politics, white men have often been represented more compared to people of color. There has only been one black president, Barack Obama. All of the other 44 U.S. presidents have been white men. In other sections of U.S. politics, the number of people of color represented has gradually increased each year since the 20th century.[12]

See also[edit]

- Acceptance

- Affirmative action

- Cultural diversity

- Discrimination

- Diversity, equity, and inclusion

- Diversity training

- Functional diversity

- Gender diversity

- Heterodox Academy (viewpoint diversity in academy)

- Identity politics

- Individual and group rights

- Motto of the European Union

- Multiculturalism

- Neurodiversity

- Racial diversity

- Racial segregation

- Rainbow flag

- Sexual diversity

- Suicide in LGBTQIA+ youth

- Workplace diversity

References[edit]

- ^ "Queensborough Community College". www.qcc.cuny.edu. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ "Mapping L.A..," Los Angeles Times website

- ^ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Article 3 "General Principles", (c)

- ^ Discovery, R. S. M. "Why Workplace Diversity Is So Important, And Why It's So Hard To Achieve". Forbes. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Celis, Karen (1 November 2013). "Representativity in times of diversity: The political representation of women". Women's Studies International Forum. Pregnant politicians and sexy fathers? The politics of gender equality representations in Europe. 41: 179–186. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2013.07.007. ISSN 0277-5395.

- ^ a b c Reyes-Housholder, Catherine (2020-09). "A Theory of Gender's Role on Presidential Approval Ratings in Corrupt Times". Political Research Quarterly. 73 (3): 540–555. doi:10.1177/1065912919838626. ISSN 1065-9129.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Ferreira, Fernando; Gyourko, Joseph (2014-04). "Does gender matter for political leadership? The case of U.S. mayors". Journal of Public Economics. 112: 24–39. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.01.006. ISSN 0047-2727.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Fox, Richard L.; Lawless, Jennifer L. (2014-08). "Uncovering the Origins of the Gender Gap in Political Ambition". American Political Science Review. 108 (3): 499–519. doi:10.1017/S0003055414000227. ISSN 0003-0554.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c The Gendered Executive: A Comparative Analysis of Presidents, Prime Ministers, and Chief Executives. Temple University Press. 2016. doi:10.2307/j.ctvrdf3zm.12. ISBN 978-1-4399-1363-5.

- ^ a b The Gendered Executive: A Comparative Analysis of Presidents, Prime Ministers, and Chief Executives. Temple University Press. 2016. doi:10.2307/j.ctvrdf3zm.12. ISBN 978-1-4399-1363-5.

- ^ Ferreira, Fernando; Gyourko, Joseph (2014-04). "Does gender matter for political leadership? The case of U.S. mayors". Journal of Public Economics. 112: 24–39. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.01.006. ISSN 0047-2727.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Uberoi, Elise; Burton, Matthew (30 September 2022). "Ethnic diversity in politics and public life". The House of Commons Library. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

External links[edit]

Quotations related to Diversity (politics) at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Diversity (politics) at Wikiquote