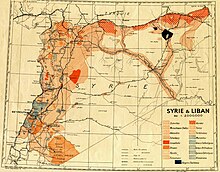

Ethnic groups in Syria

Arabs represent the major ethnicity in Syria, in addition to the presence of several, much smaller ethnic groups.

Map from La cartothèque de l'Ifpo (Institut français du Proche-Orient)

Ethnicity, religion and national/ideological identities[edit]

Ethnicity and religion are intertwined in Syria as in other countries in the region, but there are also nondenominational, supraethnic and suprareligious political identities, like Syrian nationalism.

Counting the ethnic or religious groups[edit]

Since the 1960 census there has been no counting of Syrians by religion, and there has never been any official counting by ethnicity or language. In the 1943 and 1953 censuses the various denominations were counted separately, e.g. for every Christian denomination. In 1960 Syrian Christians were counted as a whole but Muslims were still counted separately between Sunnis and Alawis.[1][2][3]

Ethnic and religious groups[edit]

The majority of Syrians speak Arabic except for a minority of Neo-Aramaic speakers and Kurdish speaking Syrian Kurds, who altogether form 5-10% of the population. Syrian Arab Sunni Muslims form ~70-75% of the populace, Christians altogether around 10%, Alawites at less than 10%, and the remaining ~5-10% consist of minor ethnoreligious groups including the Druze, Isma'ilis, and Twelver Shiite Muslims. However, these percentages are only indicative.

Arabs[edit]

The majority of Syrian Arabs speak a variety of dialects belonging to Levantine Arabic. Arab tribes and clans of Bedouin descent are mainly concentrated in the governorates of al-Hasakah, Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa and eastern Aleppo, forming roughly 20 to 30% of the total population and speaking a dialect related to Bedouin and Najdi Arabic. In Deir ez-Zor a dialect of North Mesopotamian Arabic is also spoken, reminiscent of that of medieval Iraq prior the Mongol invasions in 1258.[4]

- Arab minority groups

- Arab Christians (predominantly Melkite Orthodox and Catholic Christians)

- Druze

- Sunni Muslim and Christian Palestinians

- Arab Twelver Shias

- Arab Ismailis

Non-Arabs[edit]

Syrian Kurds form 5 to 10% of the Syrian population, the largest non-Arab minority. Other non-Arabic-speaking Muslim groups include Syrian Turkmen, who had settled Syria in Mamluk and Ottoman times, Syrian Circassians and Syrian Chechens who settled in the 19th century, and Greek Muslims who were resettled in Syria following the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. Assyrians/Syriacs in Syria form a small minority and mainly speak Eastern Aramaic dialects.

- Sunni and Alevi Turkmens

- Sunni Circassians

- Sunni Muslim Greeks

- Muslim Ossetians[6][7]

- Black people of Yarmouk Basin

- Christian minority groups

- Other groups

- Romani people of various creeds

- Mizrahi Jews

- Mandeans

- Arameans (Syriacs)[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17] in the Anti-Lebanon mountains. Western Neo-Aramaic is spoken in Maaloula and Jubb'adin.

See also[edit]

- Demographics of Syria

- Languages of Syria

- Religion in Syria

- Sectarianism and minorities in the Syrian Civil War

- Federalization of Syria

References[edit]

- ^ Hourani, Albert Habib (1947). Minorities in the Arab World. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 76.

- ^ (in French) Etienne de Vaumas, "La population de la Syrie", Annales de géographie, Année 1955, Vol. 64, n° 341, p.74

- ^ (in French) Mouna Liliane Samman, La population de la Syrie: étude géo-démographique, IRD Editions, Paris, 1978, ISBN 9782709905008 table p.9

- ^ Holes, Clive (2006). Ammon, Ulrich; Dittmar, Norbert; Mattheier, Klaus J.; Trudgill, Peter (eds.). "The Arabian Peninsula and Iraq/Die arabische Halbinsel und der Irak". Sociolinguistics / Soziolinguistik, Part 3. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter: 1937. doi:10.1515/9783110184181.3.9.1930. ISBN 978-3-11-019987-1.

- ^ "Syrian Alawites, referred to by AKP officials as Nusayris — a derogatory term not accepted by most Alevis in Turkey or Alawites in Syria — indeed can briefly be explained as follows. Some are Turkmen. They speak Turkish (...)" cf. Pinar Tremblay, "Syrian Alawites hope for change in Turkey", Al-Monitor, November 15, 2013

- ^ Dzutsati, Valery (2013). "First Ethnic Ossetian Refugees from Syria Arrive in North Ossetia". Eurasia Daily Monitor. 10 (65).

- ^ Izvestia, Yuri Matsarsky (2012). "Syrian Ossetians seek to return to Russia". Russia Beyond.

- ^ Abū al-Faraj ʻIshsh. اثرنا في الايقليم السوري (in Arabic). Al-Maṭbaʻah al-Jadīdah. p. 56.

السريان في معلولا وجبعدين ولا يزال الأهلون فيها يتكلمون

- ^ iنصر الله، إلياس أنطون. إلياس أنطون نصر الله في معلولا (in Arabic). لينين. p. 45.

... معلولا السريان منذ القديم ، والذين ثبتت سريانيتهم بأدلة كثيرة هم وعين التينة وبخعا وجبعدين فحافظوا على لغتهم وكتبهم أكثر من غيرهم . وكان للقوم في تلك الأيام لهجتان ، لهجة عاميّة وهي الباقية الآن في معلولا وجوارها ( جبعدين وبخعا ) ...

- ^ Rafik Schami (25 July 2011). Märchen aus Malula (in German). Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Company KG. p. 151. ISBN 9783446239005.

Ich kenne das Dorf nicht, doch gehört habe ich davon. Was ist mit Malula?‹ fragte der festgehaltene Derwisch. >Das letzte Dorf der Aramäer< lachte einer der…

- ^ Yaron Matras; Jeanette Sakel (2007). Grammatical Borrowing in Cross-Linguistic Perspective. De Gruyter. p. 185. doi:10.1515/9783110199192. ISBN 9783110199192.

The fact that nearly all Arabic loans in Ma'lula originate from the period before the change from the rural dialect to the city dialect of Damascus shows that the contact between the Aramaeans and the Arabs was intimate…

- ^ Dr. Emna Labidi (2022). Untersuchungen zum Spracherwerb zweisprachiger Kinder im Aramäerdorf Dschubbadin (Syrien) (in German). LIT. p. 133. ISBN 9783643152619.

Aramäer von Ǧubbˁadīn

- ^ Prof. Dr. Werner Arnold; P. Behnstedt (1993). Arabisch-aramäische Sprachbeziehungen im Qalamūn (Syrien) (in German). Harassowitz. p. 42. ISBN 9783447033268.

Die arabischen Dialekte der Aramäer

- ^ Prof. Dr. Werner Arnold; P. Behnstedt (1993). Arabisch-aramäische Sprachbeziehungen im Qalamūn (Syrien) (in German). Harassowitz. p. 5. ISBN 9783447033268.

Die Kontakte zwischen den drei Aramäer-dörfern sind nicht besonders stark.

- ^ Prof. Dr. Werner Arnold (2006). Lehrbuch des Neuwestaramäischen (in German). Harrassowitz. p. 133. ISBN 9783447053136.

Aramäern in Ma'lūla

- ^ Prof. Dr. Werner Arnold (2006). Lehrbuch des Neuwestaramäischen (in German). Harrassowitz. p. 15. ISBN 9783447053136.

Viele Aramäer arbeiten heute in Damaskus, Beirut oder in den Golfstaaten und verbringen nur die Sommermonate im Dorf.

- ^ "Hilfe für das Aramäerdorf Maaloula e.V. | an aid project in Syria".

External links[edit]

- Sectarianism in Syria (Survey Study)

- "Syria". World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples. Minority Rights Group International.

- "Guide: Syria's diverse minorities". BBC. 2011.