Wellington Botanic Garden

| Wellington Botanic Garden | |

|---|---|

A path in the Wellington Botanic Garden during spring | |

| |

| Type | Municipal botanical garden |

| Location | Wellington, New Zealand |

| Coordinates | 41°16′58″S 174°45′58″E / 41.2829°S 174.7660°E |

| Area | 61.77 acres (25.00 ha) |

| Created | 1868 |

| Operated by | Wellington City Council |

| Status | Open all year |

| Public transit access | Metlink route 2 Wellington Cable Car |

The Wellington Botanic Garden in Wellington, New Zealand covers 25 hectares of land on the side of the hill between Thorndon and Kelburn, near central Wellington. The garden features 25 hectares of protected native forest, conifers, plant collections and seasonal displays. It also features a variety of non-native species, including an extensive rose garden. It is classified as a Garden of National Significance[1] by the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture. In 2004 it was listed as a historic area with Heritage New Zealand.[2] Large sculptures and carvings are located throughout the garden. These are by artists such as Henry Moore, Andrew Drummond, Mary-Louise Browne, Regan Gentry, Denis O'Connor and Chris Booth.

History[edit]

Before the garden was established, the area was used by the Ngāti Te Whiti hapū of Te Āti Awa for growing and gathering food for Kumutoto and Pipitea pā. In 1844 the Crown took areas of the Town Belt, including land for a botanical garden, from the Kumutoto settlement, but returned some of it in 1847. Governor Grey then bought the land in 1852. In 1865 the land was sold to the Wellington Provincial Council for a public park.[3]

The garden was established on a 13 acre site in 1868, extended to 68 acres in 1871.[4]: 122 It was initially managed by the New Zealand Institute (later renamed the Royal Society Te Apārangi) and its manager James Hector until 1891.[5] The garden served three purposes: a trial ground for the government to test the economic potential of various plants, a place for scientists to collect and study native and introduced plants, and a place for the public to enjoy.[4]: 122 The New Zealand Institute planted conifers as part of a programme to import plant species and assess their potential for economic benefit to New Zealand, and these came to form a framework and shelter for other plantings.[4]: 122

Paths were laid out, native plants from other parts of New Zealand planted, and trees and plants labelled, "giving them popular Maori names instead of their scientific appellations [as] it would indeed be a pity not to see the native names of the New Zealand flora perpetuated as long as possible".[6] The first map of the garden in 1875, by John Buchanan, also included a list of all plants growing there, and a survey of native plants indigenous to the reserve.[5] The area that would later become the Soundshell Lawn was levelled in 1880, and Hector established a teaching garden there.[4]: 122

Some animals were kept at the Botanic Garden prior to the formation of Wellington Zoo in Newtown in 1906, including the "City Emu" which died shortly after being relocated to the Zoo from the garden.[7]

Wellington City Council began managing the garden in 1891, tidying up and developing various parts of the garden to improve public amenity. The garden became more popular with the public after the cable car began running in 1902 and trams started running along Glenmore Street in 1904. The council constructed a tea kiosk at the top of the cable car (1904), a playground near Anderson Park (1905), a rotunda near the duck pond (1907), and a fernery (1911). Public toilets were installed and staff buildings constructed.[4]: 123

Various gullies were filled in and levelled. A gully at what is now Anderson Park was filled in between 1906 and 1910, with later work done between 1931 and 1934 when the park was made larger. The new flat area became Anderson Park sports ground. From 1927, a ridge in the southwest of the garden was flattened and a gully filled in to form Magpie Lawn and Puriri Lawn.[4]: 123

Later developments included the Lady Norwood Rose Garden (1953) which was created over a filled-in gully, Begonia House (1960), a herb garden (1970s), an information centre (1983-1987), the Treehouse education centre (1991) and a sculpture trail (1991).

The Wellington Botanic Garden is home to several organisations, including:

- Carter Observatory, the National Observatory of New Zealand

- Wellington Cable Car Museum

- Meteorological Service of New Zealand

Features[edit]

The garden features a large Victorian-style glasshouse called the Begonia House, the Lady Norwood Rose Garden and the Treehouse Visitor Centre. There is a large children's play area, a duck pond, and glowworms visible some nights along paths in the Main Garden. There are monthly tours during autumn and spring (the garden is otherwise closed at night). In 1975 the Japan Society of New Zealand gifted a carved stone lantern that is now located in the Peace Garden adjacent to the Lady Norwood Rose Garden.[8] In 1994 the lantern was adapted to house the Hiroshima Peace Flame in recognition of Wellington's nuclear free status.

Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House[edit]

The current rose garden was established from 1950 to 1953, in time for that year's royal tour. It is named after Lady Norwood, former mayoress of Wellington, who donated £300 towards a proposed new begonia house in 1949, and in 1955 donated a fountain for the middle of the rose garden. In 1977, the fountain was replaced by a new one donated by Lady Norwood's children. The Begonia House bordering the south side of the rose garden was opened in 1960, after a donation of £20,000 by Sir Charles Norwood, former mayor of Wellington. The Norwood family made further donations for landscaping around the Begonia House and rose garden during the 1970s and 1980s.[9]

The rose garden contains 110 beds of roses, including new and traditional varieties, laid out in concentric circles around the fountain.[10] Climbing roses grow around the colonnades that surround the garden. The flowering season stretches from November to April.[11] The World Federation of Rose Societies awarded the garden a 'Garden of Excellence' award in 2015.[11]

When it was built, the Begonia House was the largest glasshouse in the southern hemisphere.[12]The Begonia House consists of two wings holding tropical and temperate plants including orchids, begonias, cyclamen, ferns and epiphytes, connected by a central atrium. A café was added to the east wing in 1981, and the west wing was extended with a large lily pond with fish and water lilies, added in 1989.[10][12] The Begonia House is a popular venue for weddings and other functions.[13]

Sound Shell[edit]

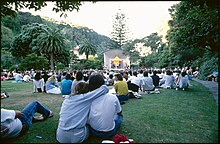

The Sound Shell Lawn was originally a teaching garden, then a rose garden. A wooden band rotunda was built in 1911 and in use until the concrete Sound Shell was built in 1953. The Wellington Bands Association proposed construction of the Sound Shell as a memorial to bandsmen who had fought and died in World War 1 and 2. A plaque on the structure states: "In commemoration of bandsmen of the Wellington District who served their king and country and of those who also made the supreme sacrifice. 1914-1918. 1939-1945. "Their sound is gone out into all lands" Psalm 19 v4."[14] The Sound Shell and lawn form a sheltered area that has been used many types of event, including band performances, music concerts, Christmas carols, open air dancing, plays, weddings and dance displays.[15] During the summer Gardens Magic season, people picnic on the lawn and trees around the area are lit up.

Duck pond[edit]

The duck pond is a naturally-formed pond, fed by the Pukatea and Pipitea streams, and has been a feature of the Botanic Garden since 1868. In times past it was known as the Frog Pond, the Lily Pond and the Swan Pond.[16] In 1996 the pond was enlarged and reshaped, and its surroundings were upgraded with a small pavilion, wetland garden and lookout points.[17] In 1998, landscape architect Stephen Dunn of Boffa Miskell won a silver award for his redesign of the pond, in a competition held by the New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects and the Landscape Industries Association of New Zealand.[18]

Events[edit]

Summer City / Gardens Magic[edit]

As part of its Summer City programme, Wellington City Council organised events in the Botanic Garden during summers from 1979 to the early 2000s, including live Shakespeare, free movies, teddy bears' picnics and free concerts.[19] The concert series continued at the Sound Shell and in 2024 celebrated 44 years of concerts. The series is titled Gardens Magic and also includes a light show.[20][21]

Tulip Sunday[edit]

Tulip Sunday is part of a spring festival held annually in the gardens, usually near the end of September. Visitors enjoy seeing the flower beds near the Founders Entrance filled with masses of tulips in full bloom, and can enjoy entertainment (often Dutch-themed) organised by Wellington City Council and sponsors.[22][23] The date of the event is decided months in advance due to the organisation required, but sometimes the tulips reach full bloom earlier or later than the scheduled date because of the weather.[24] Tulip Sunday in Wellington began in 1944 with between 10,000 and 20,000 tulips on display and music provided by a band.[25][26] The event received a boost in 1948, when the Netherlands government gave 25,000 tulip bulbs to Wellington in recognition of New Zealand's welcome to Dutch refugees after World War 2.[27]

Access[edit]

The main entrance to the Botanic Garden is the Founders Entrance on Glenmore Street, which leads past formal flower beds to the duck pond. As of 2024, a No. 2 public bus stops outside this entrance. The Centennial Entrance near the Founders Entrance provides vehicle and pedestrian access from Glenmore Street to the Lady Norwood Rose Garden, and a path from Bolton Street Cemetery past Anderson Park also leads to the rose garden. Further up Glenmore Street from the Founders Entrance are the Pipitea Entrance and West Entrance, which lead to the Puriri Lawn and Magpie Lawn. Three more pedestrian entrances provide access from the south, at Glen Road, Mariri Road and Boundary Road.[28]

At the top of the hill, the Cable Car Entrance gives access from the top of the cable car route. The Wellington Cable Car runs between the top of the Botanic Garden and Lambton Quay in Wellington's central business district. A wide paved path provides a popular downhill route, taking about 30 minutes to walk from the Cable Car entrance to the Founders Entrance.[28]

Gallery[edit]

- Wellington Botanic Gardens

-

Part of cacti and succulents garden

-

Rudderstone, by Dennis O'Connor, one of many sculptures in the Garden

-

Part of Main Garden and Floral Displays garden, with Wellington Anglican Chinese Mission Church in the background

-

Playground at the Garden

-

Begonia House

-

Aloe Polyphylla group

-

Summer event in the Dell in 1979

-

Light show at Gardens Magic

-

Concert, Gardens Magic

References[edit]

- ^ "New Zealand Gardens Trust - Wellington". www.gardens.org.nz. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ "Search the List | Wellington Botanic Garden | Heritage New Zealand". www.heritage.org.nz. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Burge, Jason (23 January 2015). "Wellington Botanical Gardens: An Origin Story". Museums Wellington. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Botanic Gardens of Wellington Management Plan 2014 [Report] (PDF). Wellington City Council. 2014.

- ^ a b Shepherd, Winsome; Cook, Walter (1988). The Botanic Garden, Wellington. A New Zealand History 1840-1987. Wellington: Millwood Press. ISBN 0-908582-79-X.

- ^ "Local and general news: The Botanic Reserve". Wellington Independent. 30 January 1871 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "CURRENT TOPICS". New Zealand Times, Volume XXIX, Issue 6203. 8 May 1907. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "The story behind Wellington's Peace Flame". Stuff. 16 November 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Cook, Walter (10 December 2009). "The Lady Norwood Rose Garden and Begonia House". Australian & Aotearoa New Zealand Environmental History Network. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Wellington Botanic Garden ki Paekākā". Wellington Gardens. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ a b Hayden (21 February 2010). "Lady Norwood Rose Garden - Wellington". The New Zealand Rose Society. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Begonia House". Archives Online. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "Begonia House Foyer". Wellington City Council. 8 March 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "Glenmore Street, sound shell". Archives Online. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Begonia Gardens, Sound Shell". Archives Online. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Hill, Marguerite (2003). "RECN512: Practicum 2003: Heritage Inventory: Wellington Botanic Garden". Research Archive at Victoria University of Wellington.

- ^ "Pond upgrade". Evening Post. 27 March 1996. ProQuest 314437287.

- ^ "Feather in cap for duckpond's creator". Evening Post. 31 March 1998. ProQuest 314538481.

- ^ Pietkiewicz, Francesca (24 February 2024). "A history of Gardens Magic, the 154-year-old Wellington concert series". The Spinoff. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Gardens Magic ready to hit all the right notes in 2024". Wellington City Council. 13 December 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Wellington.Scoop » Gardens Magic (free!) back for its 44th year". Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Tulip Sunday – Dutch Club Wellington". Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Te Wā o te Kōanga - Spring Festival". Wellington Gardens. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Wellington's tulips blooming early". Stuff. 18 September 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Tulip Sunday". Dominion. 12 October 1944 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "Tulip Sunday at gardens". Evening Post. 16 October 1944 – via Papers Past.

- ^ O'Neil, Andrea (13 September 2015). "Wellington's Tulip Sunday a reminder of Dutch war horrors - 150 years of news". Stuff. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Wellington Botanic Garden ki Paekākā Map [Pamphlet]" (PDF). Wellington Gardens. Retrieved 24 April 2024.