Linguistics wars

The linguistic wars were extended deputes among American theoretical linguists that occurred mostly during the 1960s and 1970s, stemming from a disagreement between Noam Chomsky and several of his associates and students. The debates started in 1967 when linguists Paul Postal, John R. Ross, George Lakoff, and James D. McCawley—self-dubbed the "Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse"[not verified in body]—proposed an alternative approach in which the relation between semantics and syntax is viewed differently, which treated deep structures as meaning rather than syntactic objects. While Chomsky and other generative grammarians argued that meaning is driven by an underlying syntax, generative semanticists posited that syntax is shaped by an underlying meaning. This intellectual divergence led to two competing frameworks in generative semantics and interpretive semantics.

Eventually, generative semantics spawned a different linguistic paradigm, known as cognitive linguistics, a linguistic theory that correlates learning of languages to other cognitive abilities such as memorization, perception, and categorization, while imperative semanticists and Chomsky have moved on to other linguistic notions different from deep structure that lead to more universal grammar.

Background[edit]

In 1957, Noam Chomsky (b. 1928) published Syntactic Structures, his first influential work. The ideas in Syntactic Structures were a significant departure from the dominant paradigm among linguists at the time, championed by Leonard Bloomfield (1887–1949).[1] The Bloomfieldian approach tended to prioritize small units of language in linguistic analysis, mainly phonological and morphological elements, with Chomsky criticizing Bloomfieldians as being "[t]axonomist linguistic, mere collectors and cataloguers of language". Instead, Syntactic Structures attempted higher-order analyses of language on the level of whole sentences, positing sets of rules that could procedurally generate sentences. This approach is referred to as transformational grammar, part of a larger theory of generative grammar that was pioneered by Chomsky.[1] Chomsky justified his analyses in Syntactic Structures by arguing that languages have sets of rules that govern their syntax, phonology, and morphology. According to Chomsky, semantic components created the underlying structure of a given linguistic sequence, whereas phonological components formed its surface-level structure. This left the problem of ‘meaning’ in linguistic analysis unanswered.[2]

Chomsky's Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965) developed his theory further by introducing the concepts of deep structure and surface structure, which were influenced by previous scholarship. First, Chomsky drew from Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913), specifically his dichotomy of langue (the native knowledge of a language) versus parole (the actual use of language). Secondly, Louis Hjelmslev (1899–1965) later argued parole is observable and can be defined as the arrangement of speech, whereas langue comprises the systems within actual speech that underpin its lexicon and grammar. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax also addressed the issue of meaning by endorsing the Katz–Postal hypothesis, which holds that transformations do not affect meaning, and are therefore “semantically transparent”. This attempted to introduce notions of semantics to descriptions of syntax.[1][3] Chomsky's endorsement resulted in further exploration of the relation between syntax and semantics, creating the environment for the emergence of generative semantics.[2]

Dispute[edit]

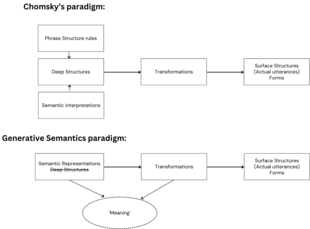

Despite initially featuring some aspects of Chomskyan syntax as detailed in Aspects, generative semantics diverged concerning the role of deep structure and semantic representation.[4] The key points of disagreement are the degree of abstractness of deep structures, maximally reduced grammatical categories and the approach to lexical decomposition.[5] Generative semantics views deep structure and transformations as necessary for connecting the surface structure with meaning. Whereas Chomsky’s paradigm considers the deep structure and transformation that link the deep structure to the surface structure essential for describing the structural composition of linguistic items—syntactic description—without explicitly addressing meaning.[2] Notably, generative semanticists eventually abandoned deep structures altogether for the semantic representation.[1]

In response to these challenges, Chomsky conducted a series of lectures and papers, known later as Remarks, which culminated in what was later known as the "interpretivist program". This program aimed to the ideas that gave rise to generative semantics such as transformations. For example, the words refuse and refusal would belong to the same category REFUSE in the generative semantics framework, but in Remarks Chomsky argued for the limitation of transformations and the separation of lexical entries for semantically related words. Remarks contributed to what Chomsky terms the Extended Standard Theory, which he thought of as an extension to Aspects. To many linguists, the relation between transformations and semantics in the Generative Semantics was the natural progression of Aspects.[5][1]

Generative semantics faced challenges in its empirical confirmation. Analyses in interpretive semantics involve phrase-structure rules and transformations that are innately codified according to Aspects,[2] drawing on Chomsky’s ideas of innate faculty in the human brain which process languages.[6] By contrast, generative analyses contained hypotheses concerning factors like the intent of speakers and the denotation and entailment of sentences. Its lack of explicit rules, formulas, and underlying structures made its predictions difficult to compare and evaluate compared to those of interpretive semantics. Additionally, the generative framework was criticized for introducing irregularities without justification: the attempt to bridge syntax and semantics blurred the lines between these domains, with some arguing that the approach created more problems than it solved. These limitations led to the decline of generative semantics.[1]

Aftermath[edit]

After the protracted debates and with the decline of generative semantics, its key figures pursued various paths. George Lakoff moved on to cognitive linguistics, which explores the cognitive domain and the relation between language and mental processes. Meanwhile, in the late 90s Chomsky switched his attention to a more universal program of generative grammar, the minimalist program, which does not claim to offer a comprehensive theory of language acquisition and use. [4] Postal rejects the idea of generative semantics and embraces natural languages discarding aspects of cognition altogether and emphasizing grammaticality. Postal adopts a mathematical/ logical approach to studying ‘natural’ languages. John R. Ross ventured to more literary-orientated endeavors such as poetry, though he maintained his transfomationalist essence as his name existed in many of the Chomskyan works. As for McCawley, he continued following the tradition of Generative Semantics until his unfortunate death in 1999. He was known for his malleable approach to linguistic theory, employing both Extended Standard Theory and Generative Semantics elements.[1]

Books[edit]

A first systematic description of the linguistic wars is the chapter with this title in Frederick Newmeyer's book Linguistic Theory in America, which appeared in 1980.[7]

The Linguistics Wars is the title of a 1993 book by Randy A. Harris that closely chronicles the dispute among Chomsky and other significant individuals (George Lakoff and Paul Postal, among others) and also highlights how certain theories evolved and which of their important features have influenced modern-day linguistic theories.[8] A second edition was published in 2022, in which Harris traces several important 21st century linguistic developments such as construction grammar, cognitive linguistics and Frame semantics (linguistics), all emerging out of generative semantics.[1] The second edition also argues that Chomsky's minimalist program has significant homologies with early generative semantics.

Ideology and Linguistic Theory, by John A. Goldsmith and Geoffrey J. Huck,[2] also explores that history, with detailed theoretical discussion and observed history of the times, including memoirs/interviews with Ray Jackendoff, Lakoff, Postal, and Ross. The "What happened to Generative Semantics" chapter explores the aftermath of the dispute and the schools of thought or practice that could be seen as the successors to generative semantics.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harris, Randy A. (2022) [1993]. The Linguistics Wars (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-74033-8.

- ^ a b c d e Goldsmith, John A.; Huck, Geoffrey J. (1996). Ideology and Linguistic Theory: Noam Chomsky and the Deep Structure Debates. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-00408-2.

- ^ Koerner, E. F. K. (2002). Toward a History of American Linguistics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-49507-8.

- ^ a b Pullum, Geoffrey (2022). "Chomsky's Forever War". National Review.[better source needed]

- ^ a b Newmeyer, F. J. (1996). Generative linguistics: a historical perspective. Routledge.

- ^ Cowie, F. (2017). "Innateness and Language.". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Newmeyer, Frederick J. (1980). Linguistic theory in America: the first quarter-century of transformational generative grammar. Academic. ISBN 978-0-125-17150-2.

- ^ Harris, Randy A. (1993). The Linguistics Wars. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-83906-3.

Further reading[edit]

- Kempson, Ruth M. (1977). Semantic Theory. Cambridge University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-521-29209-2.