Gaucho

A gaucho (Spanish: [ˈɡawtʃo]) or gaúcho (Portuguese: [ɡaˈuʃu]) is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Uruguay, Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, southern part of Bolivia,[1] and the south of Chilean Patagonia.[2] Gauchos became greatly admired and renowned in legend, folklore, and literature and became an important part of their regional cultural tradition. Beginning late in the 19th century, after the heyday of the gauchos, they were celebrated by South American writers.

According to the Diccionario de la lengua española, in its historical sense a gaucho was a "mestizo who, in the 18th and 19th centuries, inhabited Argentina, Uruguay, and Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, and was a migratory horseman, and adept in cattle work".[3] In Argentina and Uruguay today, gaucho can refer to any "country person, experienced in traditional livestock farming".[3] Because historical gauchos were reputed to be brave, if unruly, the word is also applied metaphorically to mean "noble, brave and generous", but also "one who is skillful in subtle tricks, crafty".[3] In Portuguese the word gaúcho means "an inhabitant of the plains of Rio Grande do Sul or the Pampas of Argentina of European and indigenous American descent who devotes himself to lassoing and raising cattle and horses"; gaúcho has also acquired a metonymic signification in Brazil, meaning anyone, even an urban dweller, who is a citizen of the state of Rio Grande do Sul.[4][5]

Etymology[edit]

Many explanations have been proposed, but no-one really knows how the word "gaucho" originated.[6][7] Already in 1933 an author counted 36 different theories;[8] more recently, over fifty.[9] They can proliferate because "there is no documentation of any sort that will fix its origin to any time, place or language".[10]

Resemblance theories[edit]

Most seem to have been conjured up by finding a word that looks something like gaucho and guessing that it changed to its present form, perhaps without awareness that there are sound laws that describe how languages and words really evolve over time. The etymologist Joan Corominas said most of these theories were "not worthy of discussion". Of the following explanations, Rona said that only #5, #8 and #9 might be taken seriously.[11]

| # | Proposer | Alleged root and evolution | Objection(s) | Discussed in |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Emeric Essex Vidal | Same root as English gawky (awkward, uncouth) | Earliest theory (1820), dismissed as "humorous"[a] | Paullada 1961;[12] Trifilo 1964[13] |

| 2 | Monlau and Diez | French gauche (rough, uncouth) > Argentine gaucho. | French little spoken in region. | Paullada 1961[12] |

| 3 | Emilio Daireaux | Arabic chauch (herder) > Andalusian Spanish chaucho > guttural Amerindian gaucho | Sp. chaucho is unattested.[b] That Indians could not have pronounced "chaucho" is untenable.[c] | Groussac 1904;[14] Paullada 1961;[15] Trifilo 1964;[7] Gibson 1892;[16] |

| 4 | Rodolfo Lenz | Pehuenche cachu (friend) or Araucanian kauchu (astute man) > Argentine gaucho | No proof that it was not the other way round | Paullada 1961;[15] Hollinger 1928[17] |

| 5 | Martiniano Leguizamón[d] | Quichua huajcho or wáhča (orphan, abandoned, maverick) > colonial Sp. guacho > Arg. gaucho by metathesis | Guacho > gaucho is an improbable metathesis.[e] Theory does not explain Braz. gaúcho | Groussac 1893;[18] Groussac 1904;[19] Paullada 1961;[20] Rona 1964;[21] |

| 6 | Vicuña Mackenna | Chilean Quichua or Araucanian guaso (modern sp.huaso) (countryman or cowboy) > guacho > gaucho | Same as #5. | Hollinger 1928[22] |

| 7 | Lehmann-Nitsche | Gitano (i.e. Sp. Romani) gachó (foreigner) > Andalusian gachó (bohemian, wanderer) > Arg. gaucho or Braz. gaúcho | Transition unexplained | Lehmann-Nitsche 1928[23] |

| 8 | Paul Groussac | Lat. gaudeo (I enjoy) > Sp. gauderio (peasant, one who enjoys life) > Urug. gauderio (low person, cattle rustler) > derisive *gauducho[f] > gaúcho and gaucho | *Gauducho unattested, linguistically improbable. Unlikely transition to gaucho | Groussac 1904;[24] Paullada 1961;[6] Hollinger 1928;[25] Rona 1964[26] |

| 9 | Buenaventura Caviglia, Jr | *Garrucho[g] (supp. from Sp. garrocha, a cattle pole) > gaúcho, "under negroid influence" > gaucho | Cattle pole origin implausible speculation; negroid theory untenable | Rona 1964[27] |

| 10 | Fernando O. Assunção[h] | Learned Sp. gaucho (in math. & architecture, "not level", "warped") | Elite technical word unknown to the masses | Assunção 2011;[28] Hollinger 1928.[29] |

The dialect frontier theory[edit]

A different approach is to consider that the word might have originated north of the Río de la Plata, where the indigenous languages were quite different and there is a Portuguese influence. Two facts that any theory could usefully account for are:

- The word actually exists in two forms: Port. gaúcho and Sp. gaucho, both long attested.

- Gauchos are first mentioned by name in the Spanish colonial records for present-day Uruguay, often in connection with smuggling to Brazil (see below, Origins). Thus Azara wrote (around 1784):

There is in that land, and particularly around Montevideo and Maldonado, another class of people, most appropriately called gauchos or gauderios. Commonly all are criminals escaped from the jails of Spain and Brazil, or they belong to the number of those who, because of their atrocities, have had to flee to the wilderness... When the gaucho has some necessity or caprice to satisfy, he steals a few horses or cows, takes them to Brazil where he sells them and where he gets whatever it is he needs.[30]

Hence the Uruguayan sociolinguist José Pedro Rona thought the origin of the word was to be sought "on the frontier zone between Spanish and Portuguese, which goes from northern Uruguay to the Argentine province of Corrientes and the Brazilian area between them".[31]

Rona, himself born on a language frontier in pre-Holocaust Europe,[i] was a pioneer of the concept of linguistic borders, and studied the dialects of northern Uruguay where Portuguese and Spanish intermingle.[32] Rona thought that, of the two forms — gaúcho and gaucho — the former probably came first, because it was linguistically more natural for gaúcho to evolve by accent-shift to gáucho, than the other way round.[33] Thus the problem came down to explaining the origin of gaúcho.

As to that, Rona thought that gaúcho originated in northern Uruguay, and came from garrucho, a derisive word[34] possibly of Charrua[35] origin, which meant something like "old indian" or "contemptible person", and is actually found[36] in the historical record. However in the Portuguese-based dialects of northern Uruguay the phoneme /rr/ is not easily pronounced, and so is rendered as /h/ (sounding rather like English h).[37] Thus garrucho would be rendered as gahucho, and indeed the French naturalist Augustin Saint-Hilaire, travelling in Uruguay during the Artigas insurgency, wrote in his diary (16 October 1820):

Ces hommes sans religion et sans morale, le plus part indiens ou métis, que les Portugais désignaient sous le nom de "Garruchos ou Gahuchos". (Those men without religion or morals, mostly indians or half-breeds, that the Portuguese call Garruchos or Gahuchos).[38][39]

The native Spanish-speakers of these borderlands, however, could not process the phoneme /h/, and would render it as a null, thus gaúcho.[40] In sum, according to this theory, gaúcho originated in the Uruguay-Brazil dialect borderlands, deriving from a derisive indigenous word garrucho, then in Spanish lands evolved by accent-shift to gaucho.

History[edit]

The historical "gaucho" is elusive, because there has been more than one kind. Mythologisation has obscured the topic.

Origins[edit]

Itinerant horsemen, hunting wild cattle on the pampas, originated as a social class during the 17th century. "The great natural abundance of the pampa", wrote Richard W. Slatta,

with its plethora of cattle, horses, ostriches,[41] and other wild game, meant that a skilled horseman and hunter could live without permanent employment by selling hides, feathers, pelts, and eating free beef. This pampean largess shaped the gaucho's independent, migratory existence and his aversion to a sedentary regimen".[42]

The original gaucho was typically descended from unions between Iberian men and Amerindian women, although he might also have African ancestry.[43] A DNA analysis study of rural inhabitants of Rio Grande do Sul, who style themselves gaúchos, has claimed to discern, not only Amerindian (Charrúa and Guaraní) ancestry in the female line but, in the male line, a higher proportion of Spanish ancestry than is usual in Brazil.[44] However, gauchos were a social class, not an ethnic group.

Gauchos are first mentioned by name in the 18th century records of the Spanish colonial authorities who administered the Banda Oriental (present-day Uruguay). For them, he is an outlaw, cattle thief, robber and smuggler.[45][46] Félix de Azara (1790) said gauchos were "the dregs of the Rio de la Plata and of Brazil". Summarised one scholar: "Fundamentally [the gaucho of the time] was a colonial bootlegger whose business was contraband trade in cattle hides. His work was highly illegal; his character lamentably reprehensible; his social standing exceedingly low.[47]

"Gaucho" was an insult; yet it was possible to use the word to refer, without animosity, to country people in general.[48][49] Furthermore the gaucho's skills, though useful in banditry or smuggling, were just as useful for serving in the frontier police. The Spanish administration recruited its antismuggling Cuerpo de Blandengues from among the outlaws themselves.[50] The Uruguayan patriot José Gervasio Artigas made precisely that career transition.

Wars of emancipation; independence[edit]

The gaucho was a born cavalryman,[51][50] and his bravery in the patriot cause in the wars of independence, especially under Artigas and Martín Miguel de Güemes, earned admiration and improved his image.[52] The Spanish general García Gamba, who fought against Güemes in Salta, said:

The gauchos were men that knew the country, well mounted and armed... They approached the troop with such confidence, relaxation, and coolness that they caused great admiration among the European military men, who were seeing for the first time these extraordinary horsemen whose excellent qualities for guerilla warfare and swift surprise they had to endure on many occasions.

Knowing "gaucho" to be an insult, the Spanish hurled it at the patriot militias; Güemes, however, picked it up as a badge of honour, referring to his troops as "my gauchos".[53]

Visitors to the newly emergent Argentina and Uruguay perceived that a "gaucho" was a country person or herdsman: seldom was there a pejorative significance.[54] Emeric Essex Vidal, the first artist to paint gauchos,[55] noted their mobility (1820):

They never conceive any attachment either for the soil or for a master: however well he may pay, and however kindly he may treat them, they leave him at any moment when they take it into their heads, most frequently without even bidding him adieu, or at most saying, "I am going, because I have been with you long enough". * * * They are extremely hospitable; they furnish any traveller that applies to them with lodging and food, and scarcely ever think of inquiring who he is, or whither he is going, even though he may remain with them for several months.[56]

Vidal also painted visiting gauchos from up-country Tucumán. ("Their features are particularly Spanish, uncrossed by that mixture observable in the citizens of Buenos Ayres").[57] They are not horsemen: they are oxcart drivers, and may or may not have called themselves gauchos in their home province.[58]

Charles Darwin observed life on the pampas for six months and reflected in his diary (1833):

The Gauchos, or countrymen, are very superior to those who reside in the towns. The Gaucho is invariably most obliging, polite, and hospitable: I did not meet with even one instance of rudeness or inhospitality. He is modest, both respecting himself and country, but at the same time a spirited, bold fellow. On the other hand, many robberies are committed, and there is much bloodshed: the habit of constantly wearing the knife is the chief cause of the latter. It is lamentable to hear how many lives are lost in trifling quarrels. In fighting, each party tries to mark the face of his adversary by slashing his nose or eyes; as is often attested by deep and horrid-looking scars. Robberies are a natural consequence of universal gambling, much drinking, and extreme indolence. At Mercedes I asked two men why they did not work. One gravely said the days were too long; the other that he was too poor. The number of horses and the profusion of food are the destruction of all industry.[59]

Controlling the wandering gaucho[edit]

Argentina[edit]

As cattle estates grew bigger the freely wandering gaucho became a nuisance to landed proprietors,[60] except when his casual labour was wanted e.g. at branding. Furthermore his services were needed in the armies that were fighting on the Indian frontiers, or in the frequent civil wars.

Hence in Argentina, vagrancy laws required rural workers to carry employment documents. Some restrictions on the gaucho's freedom of movement were imposed under Spanish Viceroy Sobremonte, but they were greatly intensified under Bernardino Rivadavia, and were enforced more vigorously still under Juan Manuel de Rosas. Those who did not carry the documentation could be sentenced to years in the military. From 1822 to 1873 even internal passports were required.[61]

According to Marxist[62] and other[63] scholars the gaucho became "proletarianized", preferring life as a salaried peon on an estancia to forced enlistment, irregular pay and harsh discipline. However, some resisted. "In words and deeds, soldiers contested the state's disciplinary model", frequently deserting.[64] Deserters often fled to the Indian frontier, or even took refuge with the Indians themselves. José Hernández described the bitter fate of just such a gaucho protagonist in his poem Martín Fierro (1872), a great popular success in the countryside. One estimate was that renegade gauchos comprised half of all Indian raiding parties.[65]

Lucio Victorio Mansilla (1877) thought he could discern two types of gaucho in the soldiers under his command:

The paisano gaucho (country worker) has a home, a fixed abode, work habits, respect for authority, on whose side he will always be, even against his better feelings.

But the gaucho neto (out-and-out gaucho) is the typical wandering criollo, here today, there tomorrow; gambler, quarreler, enemy of discipline; who flees military service when it is his turn, takes refuge among the Indians if he knifes someone, or joins the montonera (armed rabble) if it shows up.

The first has the instincts of civilization; he imitates the man of the cities in his dress, in his customs. The second loves tradition; he hates foreigners;[66] his luxury is his spurs, his flash gear, his leather sash, his facón (dagger-sword). The first takes off his poncho to go into town, the second goes there flaunting his trappings. The first is a cultivator, oxcart driver, cattle drover, herdsman, a peon. The second hires himself out for cattle branding. The first has been a soldier several times. The second was once part of a squadron and as soon as he saw his chance he deserted.

The first is always federal, the second is no longer anything. The first still believes in something; the second believes in nothing. He has suffered more than the city slicker, and so has been disillusioned quicker. He votes, because the Commander or the Mayor tells him to, and with that universal suffrage is achieved. If he has a claim, he drops it because he thinks it is frankly a waste of time. In a word, the first is a useful man for industry and work — the second is a dangerous inhabitant anywhere. If he resorts to the courts, it is because he has the instinct to believe that they will do him justice out of fear – and there are examples, if they don't do it he takes revenge — he wounds or kills. The former makes up the Argentine social mass; the second is disappearing.[67]

Already in 1845 a local dialect dictionary,[68] by a knowledgeable compiler,[69] gave "gaucho" as meaning any kind of rural worker, including one who cultivated the soil. To refer to the wandering sort, one had to specify further.[70] Documentary research[71] has shown the great majority of rural workers in Buenos Aires province were not herdsmen, but cultivators or shepherds. Thus, the gaucho that survives in today's popular imagination — the galloping horseman — was not typical.[72]

Brazil and Uruguay[edit]

Gauchos north of the Río de la Plata were similar to their Argentine counterparts; however there were some differences, particularly in the region straddling Brazil and Uruguay.

The Portuguese Crown, in order to conquer southern Brazil — it was disputed with the Spanish Empire — distributed vast tracts of land to a few hundred families. Labour in this region was scarce, so great landowners acquired it by allowing a social class, called agregados, to settle on their land with their own animals. Values were martial and paternalistic, for the territory went back and forth between Portugal and Spain.

Thus, the social pyramid of the borderland was divided into rough thirds: at the top, Portuguese landowners and their families; then the agregados, whose racial origins varied; and, at the bottom, the enslaved Africans whose large numbers distinguish the Brazilian borderland from similar ranching areas in the Rio de la Plata.[73]

Brazilian inheritance laws compelled landowners to leave their lands in equal shares to their sons and daughters, and since they were numerous, and those laws were hard to evade, great landholdings fractured in a few generations.[74] There were not the huge cattle estates of Buenos Aires province where, as an extreme example, the Anchorena family owned 958,000 hectares (2,370,000 acres) in 1864.[75]

Unlike Argentina, cattlemen in Rio Grande do Sul did not have vagrancy laws to tie gaúchos to their ranches.[76] However, slavery was legal in Brazil; in Rio Grande do Sul it existed until 1884; and perhaps a majority of permanent ranch workers were enslaved. Thus many horse-riding campeiros (cowboys) were black slaves.[77] They enjoyed sharply better living conditions than the slaves who worked in the brutal xarqueadas (beef-salting plants).[78] John Charles Chasteen explained why:

Ranching requires mounted workers who are not easily supervised and have ample opportunities to escape. To hold on to their slaves, estancieiros considered the dictates of humanity the most economical policy. They could easily afford it.

Land-hungry Rio Grande cattlemen bought up estates cheaply in neighbouring Uruguay[79] until they owned about 30% of that country, which they ranched with their slaves and cattle.[77] The border area was fluid, bilingual and lawless.[80] Though slavery was abolished in Uruguay in 1846, and there were laws against human trafficking, weak governments poorly enforced those laws. Often Brazilian ranchers simply ignored them, even crossing and re-crossing the border with their slaves and cattle. An 1851 extradition treaty required Uruguay to return fugitive Brazilian slaves.[81]

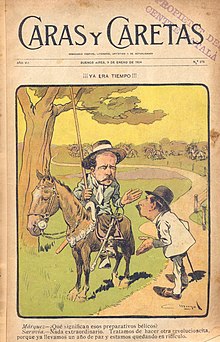

Governments found it hard to establish a monopoly of violence in the border area.[82] In the Federalist Revolution of 1893 gaúcho-manned armies led by elite families fought each other with exceptional barbarity.[83] Powerful Brazilian-Uruguayan families, like the Saraivas,[j] led mounted insurrections in both countries, even in the 20th century.[84][83] In the satirical cartoon (1904) Aparicio Saravia says it is time for "another little revolution": they have been at peace long enough and are starting to look ridiculous. This time, however, his mobile, lance-wielding horsemen were put down, and decisively, by Uruguayan troops armed with Mauser rifles and Krupp cannon, efficiently deployed by telegraph and rail.[85]

European immigration; fencing the pampa[edit]

It was official government policy, enshrined in the Argentine Constitution of 1853, to encourage European immigration. The purpose, which was not concealed, was to supplant the "lower races" of the sparsely populated interior, including gauchos,[86] whom the elite believed to be hopelessly backward. Famously, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Argentina's second elected president, had written (in Facundo: Civilización y Barbarie) that gauchos, although audacious and skilled in country lore, were brutal, feckless, lived indolently in squalor, and — by upholding the caudillos (provincial strongmen) — were obstacles to national unity. The population was so thinly spread it was impossible to educate. They were barbarians, inimical to progress. Juan Bautista Alberdi, deviser of the Constitution, held that "to govern is to populate".[87]

Once political stability was achieved the results were dramatic. From around 1875 a flood of immigrants altered the country's ethnic composition.[88] In 1914, 40% of Argentina's residents were foreign-born.[89] Today, Italian surnames are more common than Spanish.[90]

Barbed wire, cheap from 1876, fenced the pampa "and thus eliminated the need for gaucho cowboys".[90] Gauchos were forced off the land, drifting into rural towns to look for work, though a few were retained as peon labourers.[91] Cunninghame Graham, after whom a Buenos Aires street is named, and who had lived as a gaucho in the 1870s, returned in 1914 to "his first love, Argentina" and found it had greatly changed. "Progress, which he constantly lambasted, had rendered the gaucho virtually extinct".[92]

Wote S. Samuel Trifilo (1964): "The gaucho of today working on the pampas of Argentina is no more a real gaucho than is our own present-day cowboy the cowboy of the Wild West; both have gone forever."[93]

Two-thirds of Uruguay lies south of the Río Negro, and this part was fenced most intensively in the decade 1870-1880.[94] The gaucho was marginalised and was frequently driven to live in pueblos de ratas (rural slums, literally rat towns).[95]

North of the Río Negro mobile gauchos survived rather longer. A Scottish anthropologist in the central region (1882) saw many of them as unsettled.[96] European immigration to the countryside was smaller.[97] The central government failed to consolidate its power over the countryside, and gaucho-manned armies continued to defy it until 1904.[98] The turbulent gaucho leaders e.g. the Saravias had connections with the cattlemen over the Brazilian border,[99] where there was much less European immigration;[100] Wire fences did not become common in the borderland until the close of the 19th century.[101]

The revolutionary battles in Brazil ended by 1930 under the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas, who disarmed the private gaúcho armies and prohibited the carrying of guns in public.[102]

The gaucho as an icon[edit]

Argentina[edit]

In the 20th century urban intellectuals promoted the gaucho as the Argentine national icon; it was a reaction to massive European immigration and a rapidly changing way of life.

This new glorification of the once-despised plainsman came at moment when the gaucho had all but disappeared from the pampa.[103]

Jeane DeLaney has argued that the immigrant was being scapegoated for the problems of modernity; thus, the sentiment was antimodernistic, with a xenophobic, nationalistic edge.[104]

Writers variously reflecting this tendency included José María Ramos Mejía, Manuel Gálvez, Rafael Obligado, José Ingenieros, Miguel Cané, and above all Leopoldo Lugones and Ricardo Güiraldes.[105] Their answer was to go back to values that could be attributed to the old-time gaucho. However, the gaucho they chose was not the one who cultivated the land, but the one who galloped across it.

For Lugones (1913), to discern a people's true character, one had to read its epic poetry; and Martín Fierro was the Argentine epic poem par excellence. Far from being a barbarian, the gaucho was the hero who did what the Spanish Empire could not — civilise the pampa by subjugating the Indian. To be a gaucho demanded "composure, courage, ingenuity, meditation, sobriety, vigour; all this made him a free man". But in that case, asked Lugones, why did the gaucho disappear? Because, together with his virtues, he had inherited two defects from his Indian and Spanish ancestors: laziness and pessimism.

That he vanished is good for the country, because his Indian blood contained an inferior element.

Lugones' lectures, where he canonised Martín Fierro with its quarreling gaucho protagonist, had official support: the president of the Republic and his cabinet attended them,[106] as did prominent members of the traditional ruling classes.[107]

However, wrote a Mexican scholar, in exalting this gaucho Lugones and others were not recreating a real historical character, they were weaving a nationalist myth, for political purposes.[108][109] Jorge Luis Borges thought their choice of gaucho was a poor role model for Argentines.

The icon of the man on horseback is secretly pathetic. Under Attila, scourge of God, under Genghis Khan, under Timurlane, he destroys and founds vast realms, but these are fleeting. It is from the cultivator we get the word "culture"; from cities, "civilisation"; but this horseman is a passing storm... In this regard Capelle observes that the Greeks, the Romans, the Germans were tillers of the soil.[110]

Wrote musicologist Melanie Plesch:

The invention of national types, as is well known, involves a fair amount of idealization and fantasy, but the Argentine case presents an idiosyncratic feature: the mythical gaucho seems to have been drawn as an inverted image of the immigrant. Thus, the immigrant's rapacity was contrasted with the gaucho's disinterestedness, stoicism and spiritual bohemianism, characteristics that had previously been conceptualized as his proverbial laziness and lack of industry. For instance, playing on the guitar, which had previously been regarded as a symptom of idleness, was now seen as an expression of the gaucho's soul.[111]

The iconic gaucho gained traction in popular culture because he appealed to diverse social groups: displaced rural workers; European immigrants anxious to assimilate; traditional ruling classes wanting to affirm their own legitimacy.[112] At a time when the elite was extolling Argentina as a "white" country, a fourth group, those who possessed dark skins, felt validated by the gaucho's elevation, seeing that his non-white ancestry was too well known to be concealed.[113]

Today a popular movement celebrates gaucho culture.

Brazil[edit]

In Rio Grande do Sul the gaúcho has been mythified too, not in reaction to massive immigration as in Argentina, but to give the state a regional identity.[114] The main celebration is the Semana Farroupilha, a week of festivities, mass horseback parades, churrasco, rodeos and dances. It refers to the Ragamuffin War (1835–45), an elite-led separatist war against the Brazilian Empire; politicians have reinterpreted it as democratic movement. Hence, wrote Luciano Bornholdt,

the myth of the gaúcho was carefully constructed, and he was portrayed not as a poor herder, living a dangerous and dirty life, but as something much more appealing: he was praised as free, yet honest and loyal to his patron, a skilled man, even a hero in the official accounts of regional wars.[115]

The Movimento Tradicionalista Gaúcho (MTG) has an active participation of two million people, and claims to be the largest popular culture movement in the Western world. Essentially urban, rooted in nostalgia for rural life, the MTG fosters gaúcho culture. There are 2,000 Centres for Gaúcho Traditions, not only in the state, but elsewhere, even Los Angeles and Osaka, Japan. Gaúcho products include television and radio programs, articles, books, dance halls, performers, records, theme restaurants, and clothing. The movement was founded by intellectuals, apparently sons of downwardly mobile small landowners who had moved to the cities to study. Since gaúcho culture was seen as male, only later were women invited to participate. Though the real gaúchos of history lived in the Campanha (plains region), some of the first to join were of German or Italian ethnicity from outside that area, a social class who had idealised the gaúcho rancher as a type superior to themselves.[116]

Horsemanship[edit]

For many, an essential attribute of a gaucho is that he is a skilled horseman. Scottish physician and botanist David Christison noted in 1882, "He has taken his first lessons in riding before he is well able to walk".[117] Without a horse the gaucho himself felt unmanned. During the wars of the 19th century in the Southern Cone, the cavalries on all sides were composed almost entirely of gauchos. In Argentina, gaucho armies such as that of Martín Miguel de Güemes, slowed Spanish advances. Furthermore, many caudillos relied on gaucho armies to control the Argentine provinces.

The naturalist William Henry Hudson, who was born on the Pampas of Buenos Aires province, recorded that the gauchos of his childhood used to say that a man without a horse was a man without legs.[118] He described meeting a blind gaucho who was obliged to beg for his food yet behaved with dignity and went about on horseback.[119] Richard W. Slatta, the author of a scholarly work about gauchos,[k] notes that the gaucho used horses to collect, mark, drive or tame cattle, to draw fishing nets, to hunt ostriches, to snare partridges, to draw well water, and even—with the help of his friends—to ride to his own burial.[120]

By reputation the quintessential gaucho caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas could throw his hat on the ground and scoop it up while galloping his horse, without touching the saddle with his hand.[121] For the gaucho, the horse was absolutely essential to his survival for, said Hudson: "he must every day traverse vast distances, see quickly, judge rapidly, be ready at all times to encounter hunger and fatigue, violent changes of temperature, great and sudden perils".[122]

A popular copla was:

Mi caballo y mi mujer |

My horse and my woman |

It was the gaucho's passion to own all his steeds in matching colours.[124] Hudson recalled:

The gaucho, from the poorest worker on horseback to the largest owner of lands and cattle, has, or had in those days, a fancy for having all his riding-horses of one colour. Every man as a rule had his tropilla — his own half a dozen or a dozen or more saddle-horses, and he would have them all as nearly alike as possible, so that one man had chestnuts, another browns, bays, silver- or iron-greys, duns, fawns, cream-noses, or blacks, or whites, or piebalds.[125]

The caudillo Chacho Peñaloza described the low point of his life as "In Chile − and on foot!" (En Chile y a pie.)[126]

Extreme equestrianship[edit]

Richard W. Slatta collected instances of extreme equestrian sports practised by 19th century gauchos. To perform these required and developed skills and courage that helped gauchos to survive on the pampas.

- Crowding. Two men would spur their horses to shove against each other, each man's object being to drive his opponent to a particular place. In a variant, they raced along a narrow track; if one man could crowd the other off it, he won.

- Cinchada. An equestrian tug-of-war, tail to tail; the rope was tied to their saddles. "This contest grew out of the need for mounts strong enough to pull against a wild, lassoed steer".

- Pechando. Two horsemen galloping at full speed charged each other head on. The shock of the collision tumbled the men and perhaps the horses. The object was to recover and charge again and again until prevented by exhaustion or injury. "Pechando provided an opportunity for a gaucho to exhibit his courage and indifference to death or injury."

- Jumping the bar. A bar was placed above a corral gate with just enough headroom for a horse to pass. A gaucho galloped through, and as he did, he jumped over the bar and landed back in the saddle.

- Maroma. A variant in which the gaucho jumped from the bar onto the back of a racing wild horse or wild steer. He had to stay on until the horse was broken or the steer was killed.

- Recado. The horseman galloped across the pampa while he undid his recado (a multi-layered saddle), dropping the pieces as he went. He had to go back, snatch up the pieces and reassemble his saddle, all the time riding at full speed.

- Pialar, a particularly dangerous sport. One man galloped through a group of gauchos who lassoed his horse's legs. This threw the horse, but the man had to land on his feet holding the reins. This skill was useful for survival because the pampa was riddled with vizcacha burrows that threw horses; loss of one's mount was probable death for a solitary rider.

Gauchos routinely maltreated their horses since these were plentiful. Even a poor gaucho usually had a tropilla of perhaps a dozen. Most of those sports were banned by the elite.[127]

- La sortija. Carrying a lance, a galloping horseman had to impale a small ring dangling from a thread. Introduced from Spain, this sport is still practised in Spanish-speaking countries.

- Pato. A game resembling rugby football on horseback, but ranging over miles of terrain. Banned in its original form, pato was gentrified and is now Argentina's national sport.[128]

The higher skills were lost as the gaucho was marginalised, wrote Slatta:

Writing in the early 1920s, [a visitor] observed that the old gaucho equestrian practices had disappeared. No riders now performed the daring and dangerous maroma or pialar. [He] found that the ranch peon on the modern estancia could not "sit a really bad horse". He had lost the finely honed riding skills that allowed his gaucho predecessor to stay on virtually any mount.[129]

Culture[edit]

The gaucho plays an important symbolic role in the nationalist feelings of this region, especially that of Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The epic poem Martín Fierro by José Hernández (considered by some the national epic of Argentina)[l] used the gaucho as a symbol against corruption and of Argentine national tradition, pitted against Europeanising tendencies. Martín Fierro, the hero of the poem, is drafted into the Argentine military for a border war, deserts, and becomes an outlaw and fugitive. The image of the free gaucho is often contrasted to the slaves who worked the northern Brazilian lands. Further literary descriptions are found in Ricardo Güiraldes' Don Segundo Sombra.

Gauchos were generally reputed to be strong, honest, silent types, but proud and capable of violence when provoked.[132] The gaucho tendency to violence over petty matters is also recognized as a typical trait. Gauchos' use of the facón—a large knife generally tucked into the rear of the gaucho's sash—is legendary, often associated with considerable bloodletting. Historically, the facón was typically the only eating instrument that a gaucho carried.[133]

The gaucho diet was composed almost entirely of beef while on the range, supplemented by mate, an herbal infusion made from the leaves of yerba mate, a type of holly rich in caffeine and nutrients. The water for mate was heated short of boiling on a stove in a kettle, and traditionally served in a hollowed-out gourd and sipped through a metal straw called a bombilla.[134]

Gauchos dressed and wielded tools quite distinct from North American cowboys. In addition to the lariat, gauchos used bolas or boleadoras (boleadeiras in Portuguese)—three leather-bound rocks tied together with leather straps. The typical gaucho outfit would include a poncho, which doubled as a saddle blanket and as sleeping gear; a facón (dagger); a leather whip called a rebenque; and loose-fitting trousers called bombachas or a poncho or blanket wrapped around the loins like a diaper called a chiripá, belted with a sash called a faja. A leather belt, sometimes decorated with coins and elaborate buckles, is often worn over the sash. During winters, gauchos wore heavy wool ponchos to protect against cold.

Their tasks were to move the cattle between grazing fields, or to market sites such as the port of Buenos Aires. The yerra consists of branding the animal with the owner's sign. The taming of animals was another of their usual activities. Taming was a trade especially appreciated throughout Argentina and competitions to domesticate wild foal remained in force at festivals. The majority of gauchos were illiterate and considered as countrymen.[135]

Analogies[edit]

The gaucho in some respects resembled members of other nineteenth century rural, horse-based cultures such as the North American cowboy (vaquero in Spanish), huaso of Central Chile, the Peruvian chalan or morochuco, the Venezuelan and Colombian llanero, the Ecuadorian chagra, the Hawaiian paniolo,[136] the Mexican charro, and the Portuguese campino.

Modern influences[edit]

Gauchito, a boy in the Argentine colors and a gaucho hat, was the mascot for the 1978 FIFA World Cup.

In popular culture[edit]

- Martín Fierro is a 2,316-line epic poem by the Argentine writer José Hernández on the life of the eponymous gaucho.

- Way of a Gaucho 1952 film starring Gene Tierney and Rory Calhoun.

- The Gaucho was a 1927 film starring Douglas Fairbanks.

- La Guerra Gaucha was a 1942 Argentine film set during the Gaucho war against Spanish royalists in Salta, northern Argentina, in 1817. It is considered a classic of Argentine cinema.

- The third segment of Disney's 1942 animated feature package film, Saludos Amigos, is titled "El Gaucho Goofy", where American cowboy Goofy gets taken mysteriously to the Argentine Pampas to learn the ways of the native gaucho.

- Gaucho is the name of the 1980 album by American jazz fusion band Steely Dan, which featured a song by the same name.

- Gauchos of El Dorado was a 1941 American Western Three Mesquiteers B-movie directed by Lester Orlebeck.

- Inodoro Pereyra by Roberto Fontanarrosa is an Argentinean humor comics series about a gaucho.

- Gaucho is the name of a song by the Dave Matthews Band on the 2012 album Away From the World.

- The Gaucho is the University of California Santa Barbara mascot.

- The Jewish Gauchos is a 1910 novel by Alberto Gerchunoff about Jewish gauchos in Argentina. It was adapted into a film, Los Gauchos judíos, in 1975.

- Gaucho culture is often referred to by Borges

Gallery[edit]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ But Paullada observes: "There may be some basis for this claim since from the earliest times of the colony the clandestine trading in hides was carried on by the gauchos with British ships".

- ^ 1. "Chaucho has never been known in Spain" (Paul Groussac). 2. Chaucho is never found in colonial texts — "it is always gauderio or changador".

- ^ The Indians had their own word chaucha (vegetable). "All the Auracanian dialects, including the Quíchua, Tehuelchë, Aimarâ, are rich in the double dental consonant ch, and there is, therefore, no reason to presume that the Indian would mispronounce a word [chaucho] so adaptable to his own tongue, and return it in a mutilated form to the Spanish-speaking races": Gibson 1892.

- ^ Also espoused by Paul Groussac in his lecture to the World's Folk-Lore Congress at the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition on 14 July 1893: Groussac 1893, p. 12. He later abandoned it for a theory of his own, see below.

- ^ Guacho, far from metathesising, is still a living word in Hispanic America; why should it have changed to gaucho in the Plata region alone? For that matter guacho has not metathesised in Argentine Spanish either; it remains in vigorous use, and means "bastard".

- ^ The asterisk denotes that the word is conjectural i.e. it is not attested in any historical record.

- ^ Garrucho exists in Spanish as a specialist nautical term, but Caviglia's *garrucho, supposedly one who wields a garrocha (cattle pole) is not attested in the historical record: hence the asterisk.

- ^ The theory was originally proposed by the poet Juan Escayola, but without elaboration.

- ^ In the town of Lučenec, on the Slovak-Hungarian language border.

- ^ Hispanicized as Saravia in Uruguay

- ^ The work has been reviewed by Adelman (1993), Collier (1988), Lynch (1984), and Reber (1984).

- ^ Leopoldo Lugones in "El Payador" (1916) and Ricardo Rojas established the canonical view regarding the Martín Fierro as Argentina's national epic.[130] The consequences of these considerations are discussed by Jorge Luis Borges in his essay "El Martín Fierro".[131]

References[edit]

- ^ Tribuno, El. "El Tribuno". El Tribuno.

- ^ Fuller 2014; Holmes, "Nomad Cowboys"; Slatta 1990, p. 31.

- ^ a b c DLE, "gaucho, gaucha".

- ^ Dicionário Online Priberam de Português, "gaúcho".

- ^ Oliven 2000, p. 129.

- ^ a b Paullada 1961, p. 151.

- ^ a b Trifilo 1964, p. 396.

- ^ Rona 1964, p. 37.

- ^ Assunção 2011, 9943.

- ^ Paullada 1961, p. 155.

- ^ Rona 1964, pp. 37–8.

- ^ a b Paullada 1961, p. 152.

- ^ Trifilo 1964, p. 397 n.9.

- ^ Groussac 1904, p. 410.

- ^ a b Paullada 1961, p. 153.

- ^ Gibson 1892, p. 436.

- ^ Hollinger 1928, p. 17.

- ^ Groussac 1893, p. 12.

- ^ Groussac 1904, pp. 407–416.

- ^ Paullada 1961, pp. 153–4.

- ^ Rona 1964, pp. 88, 90.

- ^ Hollinger 1928, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Lehmann-Nitsche 1928, pp. 105–5.

- ^ Groussac 1904, pp. 410–4.

- ^ Hollinger 1928, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Rona 1964, p. 91.

- ^ Rona 1964, pp. 88, 92, 95.

- ^ Assunção 2011, 4135-4283.

- ^ Hollinger 1928, p. 16.

- ^ Nichols 1941, p. 419.

- ^ Rona 1964, p. 88.

- ^ Escandón 2019, pp. 20, 29.

- ^ Rona 1964, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Two examples are: (1) An 1813 copla mocking the besiegers of Montevideo

(2) An incident in 1817 in the town of São Borja, in the tri-border area. An angry marauder, sacking the local church, tore the earrings off a statue of the BV Mary, saying (in Portuguese) "this garrucha doesn't need them any more". The parish priest, a learned man, explained that the word meant "old indian": Rona 1964, pp. 95–6.Cuando Tía Candelaria

mellizos para,

lograrán los garruchos,

tomar la plaza.When Auntie Candelaria

drops twins

Then will the garruchos

take this town. - ^ The Charrua language became extinct in the 19th century, as did the people, but Rona points out that, most unusually for an indigenous language, it contained the phoneme /rr/, as its very name testifies: Rona 1964, p. 96.

- ^ Here his theory differs from Caravaglia's (#9, above), who also postulated garrucho but conjectured that it had been a Spanish word meaning "cattle pole wielder"; this meaning is nowhere attested. (There is indeed a Spanish word garrucho, but this refers to an item of nautical equipment, and is therefore remote).

- ^ Rona 1964, p. 93.

- ^ Saint-Hilaire 1887, p. 160.

- ^ Rona 1964, p. 95.

- ^ Rona 1964, pp. 93–4.

- ^ A reference to the ñandú.

- ^ Slatta 1980a, p. 452.

- ^ Nichols 1941, p. 421.

- ^ Marrero et al 2007, pp. 160, 168–9.

- ^ Rodríguez Molas 1964, pp. 81–2.

- ^ Trifilo 1964, pp. 396–7.

- ^ Nichols 1941, pp. 420, 417.

- ^ Trifilo 1964, p. 398.

- ^ Rodríguez Molas 1964, p. 87.

- ^ a b Duncan Baretta & Markoff 1978, p. 604.

- ^ Slatta 1980a, p. 454.

- ^ Trifilo 1964, p. 399.

- ^ Paullada 1961, p. 160.

- ^ Trifilo 1964, p. 401.

- ^ See the article on that artist.

- ^ Vidal 1820, p. 79.

- ^ Vidal 1820, p. 89.

- ^ Adamovsky 2014, p. 63. Some Argentine provincials said "gaucho" was just a Buenos Aires expression

- ^ Darwin 1845, p. 156.

- ^ Duncan Baretta & Markoff 1978, p. 600.

- ^ Slatta 1980a, pp. 450, 455, 459–461.

- ^ Salvatore 1994, pp. 197–201.

- ^ Rock 2000, p. 183.

- ^ Salvatore 1994, pp. 202–213.

- ^ Slatta 1980a, p. 463.

- ^ Sc. "el gringo" in original; but in Argentina this meant any kind of foreigner. Thus e.g. an Italian was a gringo.

- ^ Mansilla 1877, pp. 130–1. (Wikipedia translation)

- ^ Voces usadas con generalidad en las Repûblicas del Plata, la Argentina y la Oriental del Uruguay.

- ^ Francisco Muñiz, a country doctor who had practised around Luján for many yeara.

- ^ E.g. gaucho neto or gaucho alzado.

- ^ In censuses and farm records.

- ^ Garavaglia 2003, pp. 144, 145–6.

- ^ Chasteen 1991, pp. 741.

- ^ Chasteen 1991, pp. 737–743.

- ^ Chasteen 1991, p. 743.

- ^ Duncan Baretta & Markoff 1978, p. 620.

- ^ a b Monsma & Dorneles Fernandes 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Chasteen 1991, pp. 741, 742.

- ^ Chasteen 1991, pp. 750–1.

- ^ Chasteen 1991, p. 751.

- ^ Monsma & Dorneles Fernandes 2013, pp. 7–11, 15, 21–22.

- ^ Duncan Baretta & Markoff 1978, pp. 590.

- ^ a b Chasteen 1991, pp. 755–9.

- ^ Duncan Baretta & Markoff 1978, pp. 590, 610.

- ^ Love 1996, p. 566.

- ^ Bastia & vom Hau 2014, pp. 2–3.

- ^ DeLaney 1996, pp. 442–4.

- ^ Bastia & vom Hau 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Goodrich 1998, pp. 148.

- ^ a b Miller 1979, p. 195.

- ^ Solberg 1974, p. 122.

- ^ Walker 1970, p. 103.

- ^ Trifilo 1964, p. 403.

- ^ Nahum 1968, p. 66, 77.

- ^ Nahum 1968, pp. 62, 74–79.

- ^ Christison 1882, pp. 38, 43–4, 45–6. San Jorge lies just south of the Río Negro

- ^ Goebel 2010, pp. 197–8.

- ^ Rock 2000, pp. 176, 190, 196, 198, 199, 201.

- ^ Love 1996, pp. 565–7.

- ^ Slatta 1980b, p. 195. This refers to the Campanha, the ranching region of Rio Grande do Sul.

- ^ Chasteen 1991, pp. 748, 749 n.26.

- ^ Bornholdt 2010, p. 29.

- ^ DeLaney 1996, p. 435.

- ^ DeLaney 1996, pp. 434–6, 440–1, 447–8, 455–8.

- ^ DeLaney 1996, pp. 444, 446, 448, 451, 452, 454–5, 456–8, 445–6.

- ^ Goodrich 1998, p. 153.

- ^ Olea Franco 1990, p. 322.

- ^ Olea Franco 1990, pp. 312–3.

- ^ See also DeLaney 1996, pp. 445–6; Goodrich 1998, pp. 147–166.

- ^ Lacoste 2003, p. 142. (Wikipedia translation)

- ^ Plesch 2013, p. 351.

- ^ A classic thesis developed by Adolfo Prieto.

- ^ Adamovsky 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Bornholdt 2010, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Bornholdt 2010, pp. 26–27, 29–31.

- ^ Oliven 2000, pp. 128–131, 133, 135–6, 140–2.

- ^ Christison 1882, p. 39.

- ^ Hudson 1918, p. 23.

- ^ Hudson 1918, p. 24.

- ^ Slatta 1992, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Cunninghame Graham 1914, p. 5.

- ^ Hudson 1895, p. 356.

- ^ Arnoldi & Hernández 1986, p. 177.

- ^ Slatta 1992, p. 28.

- ^ Hudson 1918, p. 160.

- ^ Sarmiento 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Slatta 1986, pp. 101, 104.

- ^ Slatta 1986, pp. 100–2, 104–5.

- ^ Slatta 1986, p. 107.

- ^ Ruiza, Fernández & Tamaro 2004; Trinidad, "Ricardo Rojas (1882–1957)".

- ^ Arrigucci 1999.

- ^ Slatta 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Slatta 1992, p. 74.

- ^ Slatta 1992, p. 78.

- ^ Huberman 2011.

- ^ Slatta, Auld & Melrose 2004.

Bibliography[edit]

- Adamovsky, Ezequiel (2014). "La cuarta función del criollismo y las luchas por la definición del origen y el color del ethnos argentino (desde las primeras novelas gauchescas hasta c. 1940)" (PDF). Boletín del Instituto de Historia Argentina y Americana "Dr. Emilio Ravignani" (in Spanish). 41 (2): 50–92. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- Adelman, Jeremy (May 1993). "Review". Journal of Latin American Studies. 25 (2). Cambridge University Press: 401–402. doi:10.1017/S0022216X0000482X. JSTOR 158174. S2CID 143302774.

- Arnoldi, Henry; Hernández, Isabel (1986). Amor tirano: antología del cancionero tradicional amoroso de Argentina (in Spanish). Ediciones del Sol. ISBN 9789509413030.

- Arrigucci, Davi Jr. (1999). "De la fama y de la infamia: Borges en el contexto literario latinoamericano" (PDF). Cuadernos de Recienvenido (in Spanish). 10. São Paulo: Departamento de Letras Modernas, Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo: 19–55. ISSN 1413-8255. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-21.

- Assunção, Fernando O. (1991). Pilchas criollas: usos y costumbres del gaucho (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Emecé. ISBN 978-950-04-1121-9.

- Assunção, Fernando O. (2006). Historia del gaucho: el gaucho, ser y quehacer (in Spanish). Claridad. ISBN 978-950-620-205-7.

- Assunção, Fernando O. (2011). Historia del gaucho. El gaucho: ser y quehacer (in Spanish) (Kindle ed.). Buenos Aires: Editorial Claridad. ISBN 978-1-61860-020-2.

- Bastia, Tanja; vom Hau, Matthias (2014). "Migration, Race and Nationhood in Argentina". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 40 (3): 475–492. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.782153. S2CID 145438008. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- Bornholdt, Luciano Campelo (2010). "What is a Gaúcho? intersections between state, identities and domination in southern Brazil". (Con)textos: Revista d'Antropologia i Investigació Social. 4: 23–41. ISSN 2013-0864. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- Chasteen, John Charles (1991). "Background to Civil War: The Process of Land Tenure in Brazil's Southern Borderland, 1801-1893". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 71 (4): 737–760. doi:10.2307/2515762. JSTOR 2515762.

- Christison, David (1882). "The Gauchos of San Jorge, Central Uruguay". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 11. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland: 34–52. doi:10.2307/2841497. JSTOR 2841497.

- Collier, Simon (May 1988). "Review". Journal of Latin American Studies. 20 (1). Cambridge University Press: 208–210. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00002613. JSTOR 157342. S2CID 146275386.

- Cunninghame Graham, Robert Bontine (1914). El Río de la Plata (in Spanish). London: Wertheimer, Lea y Cía.

- Darwin, Charles (1845). Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world under the command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N. (2 ed.). London: John Murray. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- DeLaney, Jeane (1996). "Making Sense of Modernity: Changing Attitudes toward the Immigrant and the Gaucho in Turn-Of-The-Century Argentina". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 38 (3). Cambridge University Press: 434–459. doi:10.1017/S0010417500020016. JSTOR 179228. S2CID 143293372.

- Duncan Baretta, Silvio R.; Markoff, John (1978). "Civilization and Barbarism: Cattle Frontiers in Latin America". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 20 (4): 587–620. doi:10.1017/S0010417500012561. JSTOR 178563. S2CID 145421588.

- Escandón, Alfredo (2019). Linguistic practices and the linguistic landscape along the U.S.-Mexico border: Translanguaging in Tijuana (PDF) (PhD diss.). University of Southampton. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- Fuller, Alexandra (26 November 2014). "For Patagonian Ranchers, a Family Gathering Means Barbecue and Rodeo". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2021-03-23. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- "gaucho, gaucha". Diccionario de la lengua española (in Spanish) (23rd ed.). Real Academia Española. Archived from the original on 2021-03-25.

- "gaúcho". Dicionário Online Priberam de Português (in Portuguese). Priberam. Archived from the original on 2021-02-18.

- Garavaglia, Juan Carlos (2003). "Gauchos: identidad, identidades". América: Cahiers du CRICCAL (in Spanish). 30 (Mémoire et culture en Amérique latine, V.1): 143–151. doi:10.3406/ameri.2003.1615.

- Gibson, H. (1892). "The Gauchos". Notes and Queries (Eighth Series). Vol. 1. London: John C. Francis. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- Goebel, Michael (2010). "Gauchos, Gringos and Gallegos: the assimilation of Italian and Spanish immigrants in the making of modern Uruguay 1880-1930". Past & Present. 208 (208). Oxford University Press: 191–229. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtp037. JSTOR 40783317.

- Goodrich, Diana Sorensen (1998). "La construcción de los mitos nacionales en la Argentina del centenario". Revista de Crítica Literaria Latinoamericana (in Spanish). 24 (47): 147–166. doi:10.2307/4530971. JSTOR 4530971.

- Groussac, Paul (1893). Popular Customs and Beliefs of the Argentine Provinces. Chicago: Donohue, Hennebery & Co. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- Groussac, Paul (1904). "A propósito de americanismos". El viaje intelectual: impresiones de naturaleza y arte (in Spanish). Vol. 1a ser. Madrid: Victoriano Suárez. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- Guazzelli, Dante Guimaraens (2019). "ENTRE APLAUSOS E DENÚNCIAS: AS ENTIDADES DE ADVOGADOS GAÚCHOS E A INSTALAÇÃO DA DITADURA CIVIL-MILITAR (1964-1966)". Projeto História (in Portuguese). 66: 44–80. doi:10.23925/2176-2767.2019v66p44-80. S2CID 214452427.

- Holmes, Lauren (n.d.). "Nomad Cowboys: A Glimpse into the Life of the Chilean Gauchos". The Aston Martin Magazine. Photography by Helen Cathcart. Aston Martin. Archived from the original on 2021-03-24. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Hollinger, Frances C. (1928). The Gaucho (MA diss.). University of Kansas. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Huberman, Ariana (2011). Gauchos and Foreigners: Glossing Culture and Identity in the Argentine Countryside. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739149065.

- Hudson, William Henry (1895). The Naturalist in La Plata. London: Chapman & Hall.

- Hudson, William Henry (1918). Far Away and Long Ago: A History of My Early Life. New York: E.P. Dutton and Company.

- Lacasagne, Pablo (2009). "El gaucho en Uruguay y su contribución a la literatura" (PDF). Revista Interamericana de Bibliotecología (in Spanish). 32 (1). Medellín: Escuela Interamericana de Bibliotecología, Universidad de Antioquia: 173–191. eISSN 2538-9866.

- Lacoste, Pablo (2003). "La crisis argentina y la prosperidad chilena: una mirada desde Sarmiento, Hernández y Borges". Si Somos Americanos. 5 (4): 137–149. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- Lehmann-Nitsche, R. (1928). "Le mot 'Gaucho': Son origine gitane". Journal de la Société des américanistes (in French). 20 (nouvelle série): 103–5. doi:10.3406/jsa.1928.3642. JSTOR 24720065.

- Love, Joseph L. (1996). "Review: Heroes on Horseback. A Life and Times of the Last Gaucho Caudillos by John Charles Chasteen". The Americas. 52 (4). Cambridge University Press: 565–567. doi:10.2307/1008485. JSTOR 1008485. S2CID 151866994.

- Lynch, John (August 1984). "Review". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 64 (3). Duke University Press: 586–587. doi:10.2307/2514963. JSTOR 2514963.

- Mansilla, Lucio V. (1877). Una escursión a los indios ranqueles. Colección de autores españoles.t. XXXVIII-XXXIX (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Leipzig: Brockhaus. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- Marrero, Andrea Rita; Bravi, Claudio; Stuart, Steven; Long, Jeffrey C.; das Neves Leite, Fábio Pereira; Kommers, Tricia; Carvalho, Claudia M.B.; Junho Pena, Sergio Danilo; Ruiz-Linares, Andres; Salzano, Francisco Mauro; Bortolini, Maria Cátira (2007). "Pre- and Post-Columbian Gene and Cultural Continuity: The Case of the Gaucho from Southern Brazil". Human Heredity. 64 (3): 160–171. doi:10.1159/000102989. JSTOR 48506785. PMID 17536210. S2CID 36526388.

- Miller, Elbert E. (1979). "The Frontier and the Development of Argentine Culture". Revista Geográfica. 90 (90). Pan American Institute of Geography and History: 183–198. JSTOR 40992369.

- Monsma, Karl; Dorneles Fernandes, Valéria (2013). "Fragile Liberty: The Enslavement of Free People in the Borderlands of Brazil and Uruguay, 1846-1866". Luso-Brazilian Review. 50 (1 Special Issue: Brazilian Slavery and its Legacies): 7–25. doi:10.1353/lbr.2013.0003. JSTOR 43905251. S2CID 144798394.

- Nahum, Benjamín (1968). "La estancia alambrada" (PDF). In Rama, Ángel (ed.). Enciclopedia Uruguaya: Historia Ilustrada de la Civilización Uruguaya (in Spanish). Vol. 24. Montevideo: Editores Reunidos y Editorial Arca. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- Nichols, Madaline W. (1941). "The Historic Gaucho". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 21 (3): 417–424. doi:10.2307/2507331. JSTOR 2507331.

- Olea Franco, Rafael (1990). "Lugones y el mito gauchesco. Un capítulo de historia cultural argentina". Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica (in Spanish). 38 (1). El Colegio de México: 307–331. doi:10.24201/nrfh.v38i1.783. JSTOR 40298997.

- Oliven, Ruben George (2000). ""The Largest Popular Culture Movement in the Western World": Intellectuals and Gaúcho Traditionalism in Brazil". American Ethnologist. 21 (1). Wiley for the American Anthropological Association: 128–146. doi:10.1525/ae.2000.27.1.128. JSTOR 647129.

- Paullada, Stephen (1961). "Some Observations on the word Gaucho". New Mexico Quarterly. 31 (2). Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Plesch, Melanie (2013). "Demonizing and redeeming the gaucho: social conflict, xenophobia and the invention of Argentine national music". Patterns of Prejudice. 47 (4–5): 337–358. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2013.845425. S2CID 145799015.

- Reber, Vera Blinn (July 1984). "Review". The Americas. 41 (1). Cambridge University Press: 140–141. doi:10.2307/1006958. JSTOR 1006958. S2CID 148011979.

- Rocha, T.A.; Bonilha, A.L.D.L. (2008). "Formação das enfermeiras para a parturição: implantação de um hospital universitário na década de 80". Escola Anna Nery (in Portuguese). 12 (4): 651–7. doi:10.1590/S1414-81452008000400007. hdl:10183/85880.

- Rock, David (2000). "State-Building and Political Systems in Nineteenth-Century Argentina and Uruguay". Past & Present. 167 (May). Oxford University Press: 176–202. doi:10.1093/past/167.1.176. JSTOR 651257.

- Rodríguez Molas, Ricardo (1964). "El Gaucho Rioplatense: Origen, Desarrollo y Marginalidad Social". Source: Journal of Inter-American Studies (in Spanish). 6 (1): 69–89. doi:10.2307/164930. JSTOR 164930.

- Rona, José Pedro (1964). "Gaucho: cruce fonético de español y portugués". Revista de Antropologia (in Spanish). 12 (1/2): 87–98. doi:10.11606/2179-0892.ra.1964.110738. JSTOR 41615766. S2CID 142035253.

- Ruiza, Miguel; Fernández, Tomás; Tamaro, Elena (2004). "Biografia de Leopoldo Lugones". Biografías y Vidas. La enciclopedia biográfica en línea (in Spanish). Barcelona. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26.

- Saint-Hilaire, Augustin (1887). Voyage a Rio-Grande do Sul (Brésil). Orléans: H. Herluison. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- Salvatore, Richard D. (1994). "Stories of Proletarianization in Rural Argentina, 1820 - 1860". Dispositio. 19 (46, Subaltern studies in the Americas). Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, University of Michigan: 197–216. JSTOR 41491513.

- Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino (2008) [1865]. El Chacho: último caudillo de la montonera de los llanos (in Spanish). Barcelona: Lingkua. ISBN 9788498973518.

- Slatta, Richard W. (1980a). "Rural Criminality and Social Conflict in Nineteenth-Century Buenos Aires Province". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 60 (3): 450–472. doi:10.2307/2513269. JSTOR 2513269.

- Slatta, Richard W. (1980b). "Gaúcho and gaucho: comparative sócio-economic and demographic change in Rio Grande do Sul and Buenos Aires Province, 1869-1920". Estudos Ibero-Americanos. 6 (2): 191–202. doi:10.15448/1980-864X.1980.2.30624.

- Slatta, Richard W. (1986). "The Demise of the Gaucho and the Rise of Equestrian Sport in Argentina". Journal of Sport History. 13 (2, Special Issue: Hispanic American Sports). University of Illinois Press: 97–110. JSTOR 43611541.

- Slatta, Richard W. (1990). Cowboys of the Americas. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300045291. OCLC 1029032712.

- Slatta, Richard W. (1992) [1983]. Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9215-4.

- Slatta, Richard W.; Auld, Ku'ulani; Melrose, Maile (2004). "Cradle of Hawaiʻi's Paniolo". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 54 (2). Montana Historical Society: 2–19. JSTOR 4520605.

- Solberg, Carl (1974). "Farm Workers and the Myth of Export-Led Development in Argentina". The Americas. 31 (2). Cambridge University Press: 121–138. doi:10.2307/980634. JSTOR 980634. S2CID 147074152.

- Shumway, Nicolas (1993). The Invention of Argentina. Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08284-7.

- Trinidad, Zunilda. "Ricardo Rojas (1882–1957)". todo-argentina.net (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-01-23.

- Trifilo, S. Samuel (1964). "The Gaucho: His Changing Image". Pacific Historical Review. 33 (4): 395–403. doi:10.2307/3636040. JSTOR 3636040.

- Vidal, Emeric Essex (1820). Picturesque illustrations of Buenos Ayres and Monte Video, consisting of twenty-four views: accompanied with descriptions of the scenery and of the costumes, manners, &c. of the inhabitants of those cities and their environs. London: R. Ackermann. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Walker, John (1970). "Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham: Gaucho Apologist and Costumbrist of the Pampa". Hispania. 53 (1): 102–107. doi:10.2307/338719. JSTOR 338719.

External links[edit]

- Animal husbandry occupations

- Argentine folklore

- Chilean folklore

- Culture in Rio Grande do Sul

- Pastoralists

- Uruguayan folklore

- Brazilian folklore

- Latin American folklore

- South American folklore

- National symbols of Argentina

- Horse history and evolution

- Horse-related professions and professionals

- Herding

- Ethnic groups in Brazil

- Transhumance

- Gaucho culture