Cahokia people

kahokiaki | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| extinct as a tribe, descendants may have merged into the Peoria people[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| present-day United States (Illinois)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Miami-Illinois language | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion |

The Cahokia (Miami-Illinois: kahokiaki) were an Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe and member of the Illinois Confederation; their territory was in what is now the Midwestern United States in North America.[1]

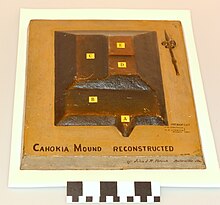

At the time of European contact with the Illini, the peoples were located in what would later be organized as the states of Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas. In the 17th-century, the Cahokia lived near the massive precontact earthwork complex that Americans named the Cahokia Mounds.[1] By then, Cahokia Mounds had been abandoned for centuries. The Cahokia people were not related to the residents of Cahokia Mounds, who were most likely Dhegiha Siouan-speaking peoples.[2]

Meanings/Associations with "Cahokia"[edit]

The word Cahokia has several different meanings, referring to different peoples and often leading to misconceptions and confusion. Cahokia can refer to the physical mounds, a settlement that turned into a still existing small town in Illinois, the original mound builders of Cahokia who belonged to a larger group known as the Mississippians, or the Illini subtribe of peoples who inhabited the area later.[3]

16th Century[edit]

Prior to 1500s[edit]

The original Mississippian inhabitants who originally built the mounds experienced the heyday of the city during the 1100s. Widely known as one of America's first cities, it was all but abandoned by the 1400s due to common depopulation drivers such as drought and resource scarcity, characteristic of the climate changes of the time. [4]

1500s[edit]

The area was repopulated by the Cahokia during the 1500s. Unlike their previous Mississippian counterparts, the Illinois Confederation populated areas outside of just the central city. They participated in small-scale agriculture and gardening, and even broke down into smaller groups for hunting and gathering during times of scarcity. [4]

17th century[edit]

French missionaries built missions in an attempt to convert the Cahokia. They built the Tamaroa/Cahokia mission in 1699 CE.[5]

18th century[edit]

In 1735, the Cahokia tribe who had been inhabiting the Tamaroa/Cahokia mission were forced to move to the Horseshoe Lake region because of mounting tensions with the French colonists. The French then built the River L’Abbė mission.[5][6] The mission was built on the first terrace of Monks Mound within the city complex.[7] These multiple missions imply that Cahokia was a large enough tribe for the French Seminary of Foreign Missions to justify their construction and operation to continue their goals.

In 1752, Shawnee and Meskwaki allies of the British destroyed the primary Cahokia settlement.[1][8] Survivors joined the neighboring Michigamea.[8] The River L'Abbe mission operated until 1752 when most of the Cahokia were considered to have left the area. From 1776 to 1784, a trading post named the Cantine was located close to Monks Mound. French farmers settled in the area soon after. [7]

The Cahokia declined in number in the 18th century, due likely to mortality from warfare with other tribes, new infectious diseases, and cultural changes, such as Christianization, which further disrupted their society.[7]

The remnant Cahokia, along with the Michigamea, were absorbed by the Kaskaskia and finally the Peoria people. The Tamaroa were closely related to the Cahokia.

19th century[edit]

Five Cahokia chiefs and headmen joined those of other Illinois tribes at the 1818 Treaty of Edwardsville (Illinois); they ceded to the United States a territory of theirs that was half of the size of the present state of Illinois.[9]

After the U.S. government implemented its Indian Removal policy in the early 19th century, the descendants were forcefully relocated to Kansas Territory and finally to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

Legacy[edit]

Although the Cahokia tribe is no longer a distinct polity, its cultural traditions continue through the federally recognized Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma.[9][10]

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Cahokia Indian Tribe History at Access Genealogy

- Malinowski, Sharon; Sheets, Anna (1998). Gale Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes, Volume 1. Gale. ISBN 0-7876-1086-0.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e May, Jon D. "Cahokia". The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ Emerson, Thomas E.; Pauketat, Timothy R. (2000). Cahokia: Domination and Ideology in the Mississippian World. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780803287655.

- ^ "Cahokia: mirror of the cosmos". Choice Reviews Online. 40 (03): 40–1759-40-1759. November 1, 2002. doi:10.5860/choice.40-1759. ISSN 0009-4978.

- ^ a b Anwar, Yasmin (January 2020). "New study debunks myth of Cahokia's Native American lost civilization". Berkeley News.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Morgan, M.J. (2010). Land of Big Rivers: French and Indian Illinois, 1699-1778. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-8564-5. OCLC 649913983.

- ^ Walthall, John A. The River L'Abbe Mission: A French colonial church for the Cahokia Illini on Monks Mound. OCLC 1107697896.

- ^ a b c White, A.J.; Munoz, Samuel E.; Schroeder, Sissel; Stevens, Lora R. (January 24, 2020). "After Cahokia: Indigenous Repopulation and Depopulation of the Horseshoe Lake Watershed AD 1400–1900". American Antiquity. 85 (2): 263–278. doi:10.1017/aaq.2019.103. ISSN 0002-7316.

- ^ a b Santella, Andrew (2007). Illinois Native Peoples. Heinemann Library. p. 13. ISBN 9781432902766.

- ^ a b Simpson, Linda. "The Tribes of the Illinois Confederacy." May 6, 2006. Accessed November 27, 2016.

- ^ "About | Peoria Tribe Of Indians of Oklahoma". Retrieved March 26, 2020.